|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

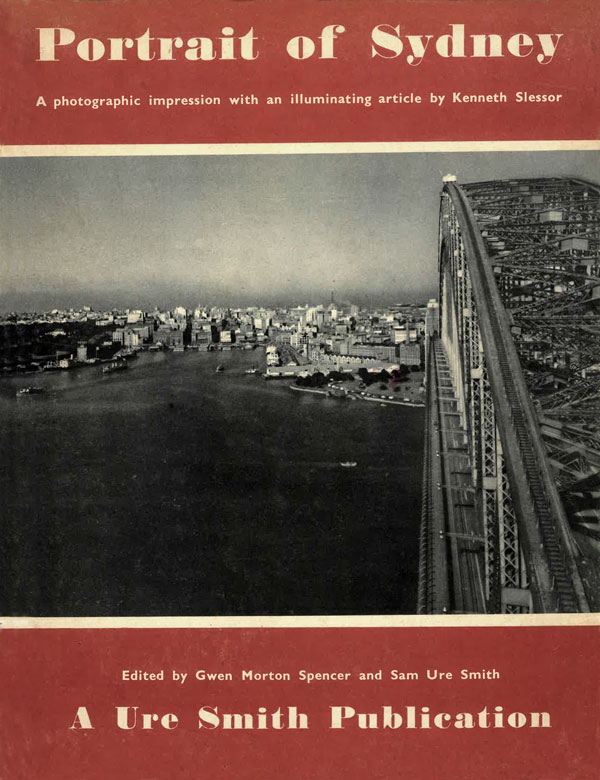

• photo-web • photography • australia • asia pacific • landscape • heritage •

• exhibitions • news • portraiture • biographies • urban • city • views • articles • • portfolios • history •

• contemporary • links • research • international • art • Paul Costigan • Gael Newton •