In The Spotlight contents page | Illustrations - photographs

essays: Gael Newton | Belinda Hungerford | Anne O'Hehir | Caroline McGregor

main Bruehl page

. EXCITING WITH A STRANGE BEAUTY PHOTOGRAPHS OF MEXICO Anne O'Hehir |  | . . The original essay was illustrated within the pages -

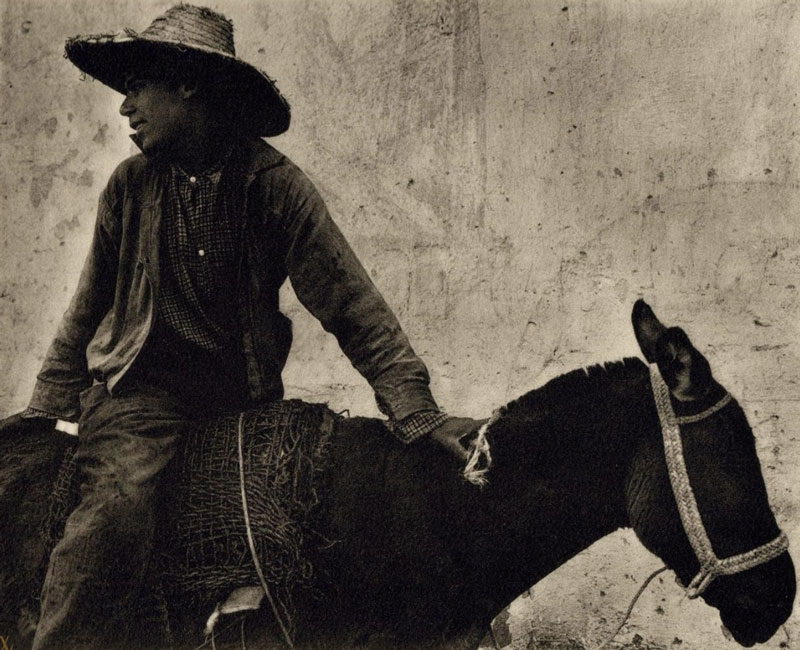

the plates for this essay are presented separately on the illustrations page I now have Anton Bruehl's Mexico photographs on the wall—most of them are of tired, simple people, unmindful of sun and flies. Bruehl has caught the hot bright sun in hard, deep blacks. Ansel Adams to Alfred Stieglitz, 9 October 1933 1 After a terrible occurrence in 1925, Mexico would be forever associated in Anton Bruehl's mind with death. For it was there on 8 July in Mexico City that his friend and mentor Clarence H White died unexpectedly at the age of fifty-four. He died of a ruptured aortic aneurism, only days after arriving on a planned four-week stay with a small group of students from his school. Neither White's wife, nor his young friend had accompanied the group: it was left to Stella Simon, one of the students, to bring the body back. Seven years later, Bruehl set off to Mexico. With him went a 4x5 Deardorff view camera and glass plates, a 4x5 Graflex Speed Graphic camera and film, a tripod, and chemicals. Once in Mexico City, he hired a local as a guide, translator and assistant. After spending over a decade among the hustle of big city life and the wooded greenery of Connecticut, he can only have felt nostalgia for his birthplace, to be back photographing in a harsh and intense light. In Mexico Bruehl made a body of work from which he chose a group to be shown at the Delphic Studios in New York in October the following year.2 This coincided with the launch of his book Photographs of Mexico, in which twenty-five images were reproduced as sumptuous and velvety collotypes printed by the Photochrome Company of New York. Put together by graphic designer AG Hoffman, it is sparse and elegant in its layout; a small preface by Bruehl precedes a list of the plates, which are then printed free from text or caption. It appeared in a limited, numbered edition of 1000 and went on sale for $12.50 – an expensive and classy production.3 The idea of making a book would have appealed to Bruehl. Book production was close to White's heart and he believed that reaching a large public through the reproduction of photography in the printed media a worthy goal. Indeed, a 1908 issue of Alfred Stieglitz's exquisitely printed magazine Camera Work – one of the greatest achievements in photographic print history – had been devoted to him. White had even employed Frederic W Goudy, one of the most important typographers in the United States, to teach a course on design at his school. Bruehl's contemporaries were busy with putting together their own photobooks around this time. In 1929, Steichen the photographer by Carl Sandburg was published and Ansel Adams, two years Bruehl's junior, had produced Taos Pueblo in 1930 – he published 108 copies at $75 apiece, all of which sold.4 The art of Edward Weston came out in 1932. Although books on Mexico had appeared earlier – long-time Mexican resident, German-born Hugo Brehme's Picturesque Mexico in 1923 was popular and good, and his Pueblos y Paisajes de Mexico would appear in 1932 – it was not the tradition of the arty, limited-edition portfolio that Bruehl had set his sights on. Opening Bruehl's book on Mexico, the first thing the reader encounters is Bruehl's sparse and economic introduction, three short paragraphs. In a bold flourish, Bruehl tells his audience straight up what the book is not: 'they show nothing of Mexican cathedrals, public buildings, or ruins. The do not undertake to present Mexico.5 This is a little unsettling and surprising. If not a portrait of Mexico, what could be Bruehl's intention? The book contains one landscape and one still life of sombreros; otherwise people and, within those, six extreme close-ups. Bruehl must have seen Weston's exhibition of Mexican photography at Delphic Studios early in the year and seen or owned a copy of Anita Brenner's Idols behind altars (1929), in which Weston's photographs appeared, and realised that Weston had done a good job recording the folk art of the country – better leave well enough alone! However, he may have been inspired by Weston's new and dramatic breakthrough way of making portraits, something Weston called his heroic heads, photographing in the direct sun and from below.6 Previous photographers exploring indigenous and folk cultures had also made extensive use of the close-up portrait to great effect. Edward S Curtis's study of Native Americans, published in twenty volumes between 1907 and 1930 was a landmark and would have been especially widely known and admired, particularly among fellow Pictorialists, such as White. Robert J Flaherty's work on the Inuit was also important. Adams also employed the close-up in his Taos Pueblo, interleaving them with photographs of New Mexican architecture – images that echo those of Curtis. In a number of his images, Bruehl gets low with this camera, shooting from below to impart in his sitters a monumental quality. This is particularly evident in the image The servant, Cuautla (La Criada, Cuautla), in which the subject increases this sense of the heroic by staring into the distance. This way of shooting reflects Bruehl's observation that the faces he encountered were 'exciting with a strange beauty, a beauty that has in it centuries of suffering’ and that their 'eyes sparkle with a strange pride’.7 More often, though, he situates his sitter straight on so that they engage with a gaze straight into the camera lens, giving the portraits a sense of immediacy and intimacy.8 The relationship that existed between the sitter and the photographer – when using a view-camera the photographer's face and eyes are not covered by the camera – becomes that between the sitter and the viewer. An illusion, of course, but one that makes the images come alive. At the centre of Bruehl's book is an extreme close-up image of a teenage girl named Dolores. And at the centre of that image, reflected in her eyes, is the tiny but distinct image of the photographer himself. Delores might be from another country, and for us from another time, but she looks like any slightly bored, surly teenager anywhere. Her personality, which Bruehl allowed her to own, comes through in this image and engages the viewer. The handling of light is masterly – the face is nearly all in shadow, allowing the brilliant reflections in her eyes to shine with greater intensity. Strangely, for a photographer who loved the studio and who spent hours arranging and controlling everything, there is a remarkable sense of autonomy of the sitter here. Similarly, in The girl (La Nina), the little girl is sitting on matting and, although comforted by two women on either side, she is allowed to cry – in a sense, just to be. The babies in other images either scowl at Bruehl or sleep. An aspect of the book that is somewhat unusual for its time, is that in a couple of instances Bruehl gives names to his sitters. Thus they cease to be only symbolic of something else and counter a prevailing trend, 'the abstraction of the Mexican ... into a faceless symbol of a timeless world’.9 Bruehl's Mexican work is nearly always discussed in the context of American relationships with Mexico, and in a deliberate way Bruehl played into nuances of this relationship, for like any great advertising man he was masterly at reading his audience. As Bruehl himself told the reader, his images do not show the churches or the famous archaeological sites; neither do they show any industry, foreigners or urban modern life. Following the bloodshed of the revolution between 1910 and 1920 that ended the regime of Porfirio Diaz, the government was keen to promote the country as one no longer in the grip of banditry and violence. Rather, they at first wanted it to be seen as modern and forward looking, and increasingly as a timeless and idyllic land of peasants in harmony with nature, fulfilled spiritually through a colourful communal life—a simplification which some (but few) condemned as 'sheer Roussian romanticism.'10 Although shot with this notion of timelessness – the people's 'simple mode of living' is stressed in the preface – Bruehl's photographs negate, if subtly, this accepted way of approaching the 'other’. Bruehl had been a resident in the United States for over a decade when he took these photographs, but it is important in this context to note that he remained in many ways an 'Aussie bloke'; it was not as an American that he approached his subjects. He would have been free from prevailing cultural and societal assumptions, and it is partly for this reason that he was able to gain rapport: he writes, 'everywhere I found the people friendly and patient with the mechanics of the camera, and so completely unaffected’.11 Perhaps this is also a reflection of how much, like his sitters, Bruehl was being himself. Bruehl's is a vision that situates beauty as a part of quotidian life. Again, this reflects prevailing ideas about Mexico. In Idols behind alters, for example, Brenner wrote: Nowhere as in Mexico has art been so organically a part of life, at one with the national ends and the national longings, fully the possession of each human unit, always the prime channel for the nation and the unit.12 Bruehl looks down to the anonymous hands of a potter. His hands, caked in clay, become an extension of his pot—big, rough, utilitarian, unglazed. It is enlightening to compare this to Weston's Hand of the potter (Amado Galvan) 1926, which appeared as the frontispiece to Brenner's Idols behind altars and which shows us the hand of Amado Galvan, one of the first folk potters in Mexico to achieve fame. Weston points the camera up: the hand and pot are dramatically held aloft in a theatrical gesture with religious overtones.13 Weston had little if any interest in the local peasant population, photographing them rarely and then often from behind, characteristically interested in them in formal rather than personal terms. However, there was more here for Bruehl, who was very much a maker – a woodworker, boat builder and inventor, who loved spending days constructing his sets and solving construction problems. It is therefore no surprise that this was a quality he prized in others, and it is this respect that is captured in his photographs. Bruehl's Photographs of Mexico is in many ways about relationships. In contrast, the work of another photographer, Paul Strand, is about the difficulty of relationships and of photographing people. Strand was in Mexico a little later in the same year as Bruehl and remained there through the following two years, photographing, teaching and making the film The wave (Los Redes). In 1940 he also put together a portfolio of his Mexican photographs.14 This book of twenty photogravures echoes Bruehl's – it has the same title, a similar layout, and images that are often unexpectedly close compositionally. Unlike Bruehl, however, Strand found that the people he encountered did not like to be photographed and so, as he had done previously in 1916, he used a special mirror lens in his camera and recorded people at a ninety-degree angle15 – shooting on the sly, his subjects unaware that they were the focus of his attention. Unpredictably, even Strand, whose leftist political philosophy had become codified as Marxist through his Mexican experience, presents the viewer of his portfolio with a vision that is familiarly timeless; the realities of a modern Mexico do not intrude, as if ‘Strand undoubtedly sensed that the peasant life he witnessed would not be quickly transformed’.16 The pull of prevailing ideas about Mexico as an untouched, idyllic land of peasants was difficult for even the most politically engaged artist to buck against, it seems, and it is the overlaying theme in Bruehl's treatment. But mitigating this story of the exotic are small reminders of the modern and the particular that keep breaking in: clothes held together with safety pins, a newspaper, a small brooch with a photographic image (the woman's husband, lost in the revolution, or her son lost in more recent violence?). Detail and texture is lovingly observed, through sharp focus and close observation, intensifying our sense of being present. Bruehl's images have a particular quality, a distinctive sharpness and look, which can be attributed to the negatives he used, many of which were glass plates – an anachronistic choice in the early 1930s, especially for a young practitioner. That the more established and 'set-in-their-ways' Pictorialists might have continued to make use of glass negatives is not surprising; that a young, innovative practitioner did so was a statement of intent. Many of the themes and preoccupations found in Bruehl's Mexican images can be traced back to the ghostly presence of White. Bruehl's admiration for and loyalty to his teacher is moving: in later years Bruehl recalled that he was 'a wonderful and great man. I owe everything to him.'17 Further reflecting the closeness of their relationship is the weekends they would often spend together in Connecticut, in White's downtime; Bruehl 'kept the fires going, and White cooked while they both talked about art for hours on end’.18 White had hoped to use his own trip to Mexico to restart his photography practice, which had lapsed given the pressures of his teaching commitments. In many ways it is tempting and plausible to see Bruehl's Mexican portfolio as a symbolic completion of White's planned project – significantly, Bruehl never strayed far from Mexico City, where White died. Furthermore, intimate scenes of his family dominated White's oeuvre. Quiet, dreamy images with very simple elements of form and a masterful use of light: images that show 'harmonious relationships between women and children’.19 Women and children in relationship also dominate Bruehl's book, which contains no less than four mother and child images. The men are identified by the work they do – the potter, the boatman, the fruit seller – reflecting Bruehl's own approach to life but also an echo again of White, who was a socialist in a romantic, Whitmanesque tradition that celebrated the life of the common labourer. White's life was simple, eschewing materialistic concerns, and the overall mood and feel of Bruehl's Mexican photographs look back to White and a Pictorial sensibility – though with Bruehl's straightforwardness and dislike of pretentiousness. As his practice evolved, Bruehl's images would continue to blend modernist and more Pictorialist aesthetics – of narratives that are often somewhat sentimental – with one stressed more than the other depending on the nature of the assignment. Surprisingly Bruehl, a Catholic, does not present the viewer with images of the Spanish-flavoured Catholicism of Mexico, as do so many other photographers, including Strand.20 Brought up in the Irish-Catholic tradition of the Christian Brothers in Melbourne, Bruehl was possibly startled by the flamboyance he saw in Mexico. Religious iconography is encoded in his book, however, as in his 'mother and child' images. The notion that people in their everyday existence were constantly in touch with larger, metaphysical and spiritual realms, and that religion was not 'tacked on' to everyday living but intrinsically at the heart of it, was another commonly held view of Mexico. This way of thinking is one that Bruehl may easily have encountered in the pages of Idols behind altars, where it is evident even in the very language Brenner uses: 'a land that moves, a people not dead, nor now in resurrection, but constantly reborn’.21 The mood of Bruehl's Mexican photographs is overwhelmingly sombre, even melancholic; only Lucretia shows even the hint of a smile – a coy, small thing.22 And then the viewer comes to the final image of the book, the only landscape. On the road to Toluca is an image devoid of people, the barren but bleakly beautiful and hilly landscape is dominated by a towering, backlit cactus, so large that it cannot be contained in the viewfinder and breaks free at the top of the photograph. It is Bruehl's Golgotha image, a grave marker for his friend who met his sudden death in Mexico. When Bruehl's Photographs of Mexico appeared in 1933, he was jumping on the Mexican bandwagon. The wider interest in Mexico was manifesting as enormous amounts of cultural exchange, which in turn served to further fan the flames of enthusiasm. Certainly Bruehl was helped on by one of Mexico's champions in New York, the charismatic and flamboyant Alma Reed. For Reed, as for Bruehl, thoughts of Mexico were forever bound up with a tragic death. An American newspaper correspondent, she had been working in Mexico in the 1920s when she fell love with the socialist politician and governor of Yucatan, Felipe Carrillo Puerto, who was assassinated in January 1924 by his political rivals only days before their wedding. By the late 1920s, Reed was in New York. Brenner introduced her to the Mexican muralist Jose Clemente Orozco in 1928 and Reed, her passions again engaged, took on promoting Orozco's art with a characteristic fervour. Seeking a platform on which to bring him to the public's notice, Reed opened Delphic Studios on the top floor of an apartment on East Fifty-Seventh Street. Though part of the space was permanently devoted to Orozco's work, Reed also showed works by other Mexican and American artists, and a selection of Breuhl's non-commercial photography was shown here in 1931. In later interviews, Bruehl asserted that he was in Mexico on holidays and that the images he made there were 'for his own pleasure'23, stressing the personal nature of the project. That Reed was behind it all somehow seems likely – a woman who made 'the most of every moment in order to arrive at some climax'24 was no doubt rather inspiring. In addition to the gallery, Reed had established a publishing arm, naturally to promote Orozco in the first instance, but also other things Mexican. Reed was no doubt on the lookout for other projects and Bruehl – who was young, enthusiastic, already critically acclaimed, and had the White-Mexico connection – was a worthy contender. Photographs of Mexico won praise from many quarters at the time of its publication, in Mexico and the United States. It was chosen by the American Institute of Graphic Arts as one of the Fifty Fine Books of the Year in 1933, and then as Best Illustrated Book for 1931-33 the following year. Perhaps more telling, however, were the comments Bruehl received from his peers. Orozco and Adams, for example, committed themselves to print, commenting on the beauty of its reproductions and its sincerity, and in a comment that echoes White's views and handbooks for his school, they praised the book for exhibiting 'good taste’. ‘This is certainly Mexico as revealed by great photography' Orozco enthused, even going so far as to claim that 'anything that may be expected from the art of painting is there'25 (although it could be argued that Orozco's interests in promoting the book were not exactly the most impartial). Mexico represented something very particular to Anton Bruehl. The images he made there resulted in a body of work that is one of the most deeply felt, intensely seen, beautifully resolved and personal of his career; surely a worthy tribute to his great friend and mentor. In a sense, though, the work he created there represents an ending rather than a beginning. Bruehl drew a line under his career to that point, though perhaps not deliberately or consciously. The studio beckoned. It became a site where he created his own world: fabricated and artificial. Bruehl went on to build a successful career as one of the most sought-after commercial photographers of the 1930s, and becoming in particular one of the major players in the development of early colour. His next book, Color sells – published by Conde Nast in 1935 and featuring sixty-four of his editorial and advertising images – reflected this new allegiance. the plates for this essay are presented separately on the illustrations page

Notes - MS Alinder & AG Stillman (eds), Ansel Adams:letters and images 1916-1984, Little, Brown and Company, Boston, Toronto, London, 1988, pp 58-9.

- The exhibition ran 2-15 October 1933. The images were shown on the west coast at the Ansel Adams Gallery, San Francisco, and at Gallery 683 Brockhurst in Oakland (a gallery in the home of fellow photographer Willard van Dyke).

- The Mexican curator and writer Olivier Debroise judged that 'it is, to date, the best-printed book of Mexican photographs! O Debroise, Mexican suite: a history of photography in Mexico, trans S de Sa Rego, University of Texas Press, Austin, 2001, pp 138-9.

- V Aletti, 'Ansel Adams, Taos Pueblo', in A Roth (ed), The book of 101 books: seminal photographic books of the twentieth century, PPP Editions in association with Roth Horowitz, New York, 2001, p 58.

- A Bruehl, Photographs of Mexico, Delphic Studios, New York, 1933, np. Signed and numbered by the artist. The National Gallery of Australia has no 113. A later trade edition, which had the addition of text on the once blank pages opposite the images by writer and journalist SL Woodall was published by the US Camera Publishing Corporation, New York, in 1945.The text is a generalised history and discussion of Mexican culture. The National Gallery of Australia also holds 19 gelatin silver photographs of images from the book Photographs of Mexico, ten vintage prints that were most probably printed for exhibition in 1933, and nine photographs printed for exhibition in the 1970s.

- B Abbott, In focus Edward Weston: photographs from the J Paul Getty Museum, Paul Getty Publications, Los Angeles, 2005, p 46.

- Bruehl. np.

- Bruehl would later advise that ninety-nine times out of a hundred a straight head on shot is the most effective! L McAtee, 'Plan every picture, advises Anton Bruehl! National Gallery of Australia Research Library, Anton Bruehl Papers [NGARL-MS36].

- J Oles, South of the border: Mexico in the American imagination, 1917-1947, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, 1993, p 79.

- Anthropologist Oscar Lewis, quoted in H Del par. The enormous vogue of things Mexican: cultural relations between the United States and Mexico, 1920-1935, University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, AL, 1992, p 124.

- Bruehl, np.

- A Brenner, Idols behind altars, Payson &c Clarke, New York, 1929, p 32.

- Oles,p 117.

- P Strand, Photographs of Mexico, foreword by L Hurwitz, Virginia Stevens, New York, 1940, np.

- AM Lynden, In focus Paul Strand: photographs from the J Paul Getty Museum, Paul Getty Publications, Los Angeles, 2005, p 50.

- N Rosenblum,'Strand/Mexico! in C Nager & F Ritchin (eds), Mexico through foreign eyes / visto porojos extranjeros, WW Norton &c Company, New York, London, 1993, p 28.

- A Bruehl, unpublished interview with PC Bunnell,7July I960, typescript copy 2010 courtesy Dr P Bunnell; National Gallery of Australia Research Library, Anton Bruehl Papers [NGARL-MS36],

- MP White Jr,'Clarence H White: artist in life and photography! in WI Homer (ed), Symbolism of light: the photographs of Clarence H White, Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, 1977,p28.

- B Yochelson, 'Clarence H White: peaceful warrior! in M Fulton {ed),Pictorialism into modernism: the Clarence H White School of Photography, Rizzoli, New York, 1996, p 16.

- In his book, Strand included images of wooden statues known as bultos interleaving the portraits.

- Brenner, p 32.

- Indeed, Lucretia has always seemed like the odd one out. No peon's daughter here— Lucretia is most likely the daughter of Mexican muralist painter Jose Clemente Orozco. Eugenia Lucrecia Orozco y Valladares,Orozco's youngest child and only daughter, was born 13 November 1927. B Cruzjose Clemente Orozco: Mexican artist, Enslow, Springfield, NJ, 1998, p45.

- M Stagg, Anton Bruehl! Modem Photography, vol 15, no 9, September 1951, p 96.

- According to the painter lone Robinson, quoted in Delpar, p 148. In her study of Anton Bruehl, Bonnie Yochelson also suggests the possibility that the book was commissioned by Reed, and that she introduced Bruehl to artists in Mexico City. B Yochelson, Anton Bruehl, exhibition catalogue, Howard Greenberg Gal lery, New York, 1998, p 6.

- JC Orozco,'Bruehl's Mexico!Art Digest, vol 8, no 1,1 October 1933, p 19.

In The Spotlight contents page | Illustrations - photographs essays: Gael Newton | Belinda Hungerford | Anne O'Hehir | Caroline McGregor main Bruehl page |