John F. Williams

a photo-history 1933 - 2016

Gael Newton AM 2004

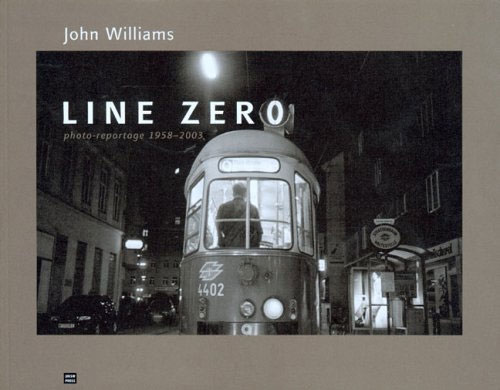

Essay originally published with the May 2004 publication: John Williams - Line Zero: Photo Reportage 1958-2003

Beginning as an amateur in the late 1950s, by the mid-1970s John Williams was a prominent figure among the booming new wave of 'art photographers' in Australia. He was from the outset more informed, experienced and articulate as a practitioner, teacher and critic than most of his younger contemporaries. It seemed to those of us who entered the field in the 1970s, that photography was also young and without the baggage of a lineage from the preceding era of the late 1950s and 60s.

When — and if — we ever thought about them, the post-war decades had only a ghostly presence as an era dominated by commercial photography rather than true 'art'. So when in 1989 Sandra Byron, Curator of Photography at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, mounted Williams's first major retrospective, the crucial evidence in front of us was largely ignored. His body of work in the sixties was clearly the precursor to the new attitudes and styles of personal documentary work in the seventies and not a tail-end of an earlier era.

Having had such a life in photography ahead of the 70s generation, John Williams sees his own age-cohort as something of a lost generation; born after World War I and living through the Depression of the 1930s but mature before the rise of affluent post-World War II baby boomers. As the late child of a World War I veteran, Williams's sense of history was shaped by hearing of his father's terrible wartime experiences.

Born in Liverpool, Williams senior immigrated to Sydney in 1925 and married a young professional musician in 1930. The couple lived at Maroubra where their son John Frank grew up and was educated at Sydney Technical High School from where he matriculated in 1950. At school, young Williams was more interested in his German language studies and history. At Sydney Technical College, he undertook part-time studies in mechanical engineering — a vocation 'never of any interest' but dictated by the family finances, which ruled out university.

Williams found time between work as a draughtsman and his night classes to discover the new generation of broadly based cultural historians such as Barbara Tuchman, Eric Hobsbawn and A.J.P.Taylor. He became interested in photography through his first wife, a teacher with a camera and some darkroom equipment. Prior to their marriage in 1958, she gave him a copy of the catalogue from the 1955 blockbuster photography exhibition the Family of Man mounted by Edward Steichen at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, which was sent in multiple copies on a long running world tour.

The exhibition sought to promote world peace and understanding by reflecting the common humanity of different races and nations across the world. Williams was moved by the content, scale and emotional impact of the exhibition when it was shown in Sydney in 1959. He was not alone; it was a pattern repeated in the careers of many later well known photographers in Australia and elsewhere.

Williams soon after acquired a good quality camera; the square format twin lens Rolleicord. He had no means to make contact with like-minded modern photographers in Sydney, David Moore and Laurence LeGuay who were the two Australians included in the Family of Man. There were no adult education courses in photography so Williams joined local camera clubs but soon found the members were interested in old-fashioned styles and obsessed with technique. He turned instead to foreign books and magazines from the Sydney Public Library but remained within the clubs for some years, while developing his lecturing and writing skills.

By 1965 when he left to travel overland to London with his wife, John Williams was an accomplished documentary photographer. He had already made a powerful suite of images around 1964-69 showing beach culture in the areas of Sydney where he had grown up and still lived.

One marvellous image taken at Clovelly shows a sort of antipodean take on Edouard Manet's 1863 painting, Déjeuner sur l'erbe in which instead of a European pastoral we have a group of older women bathers in modern swimsuits, who are seen happily sun tanning and chatting on the tough concrete promenade attended by piles of accessories testifying to a new consumer culture.

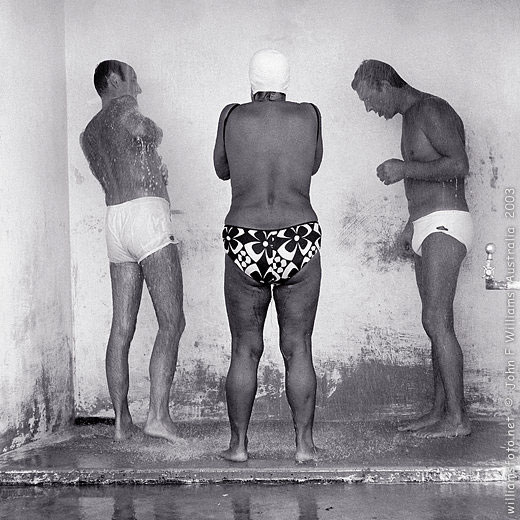

Similarly his trio of two men and a deeply tanned woman in a flower-power bikini showering together at Bronte, speak of a new social informality well beyond the preserve of the youth of the 'counter culture' of the sixties. As much as Max Dupain's geometrically ordered beach pictures of the 1930s -1940s, Williams's 1960s beach pictures are icons of their era.

His travel experiences and residence in England for five years unleashed a flood of new works which now form a major part of his canon. The images owe a considerable debt — like all his preceding Australian work — to the spontaneity and human interest subject decisive moments made famous by French photojournalist Henri Cartier-Bresson.

The latter's lavish monograph The Decisive Moment had been published in 1952, but his work was mostly disseminated through European and American Photography magazines and Year Books. Williams however, used the 2¼ square format Rolleicord which had a different dynamic to the rectangular of the 35mm 'miniature' cameras used by Cartier-Bresson and many photojournalists in the 1960s. In these years Williams cropped his images to conform to the fashionable rectangular format. After seeing the square format prints by new wave American documentary photographer Diane Arbus in the 1970s, Williams reprinted his earlier images uncropped, in which form, they are now always presented.

Williams felt very at home in England and Europe and his adopted milieu effectively became his spiritual and intellectual axis mundi. Working part time in the British aerospace industry to earn a living, Williams main interest was in photography and he joined various cameras clubs, exhibiting with British photographer Raymond Moore and others as the Group of Seven at the Architectural Association gallery in 1967. In 1969 these promising developments were interrupted when for family reasons Williams and his wife travelled back to Australia for what was intended as a brief visit. They soon found that changes in exchange rates prevented their return to London.

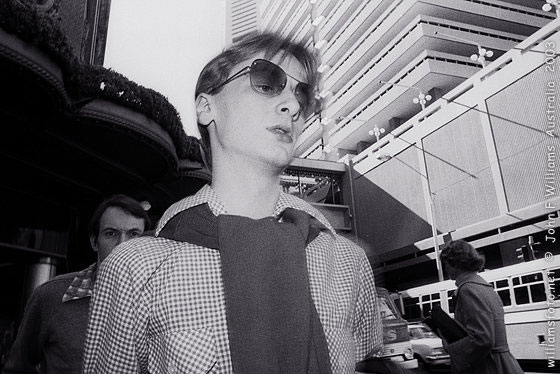

Williams would feel uprooted. In Europe Williams had concentrated on street reportage usually showing his subjects quite directly at home in their environment. In line with trends in British photography towards less obvious and singular kinds of 'decisive moment' compositions (for example, as represented in the work of Tony Ray Jones) many of Williams' images in the late 1960s became quite complex. The mood was 'off set' emotionally by the use of counterpointed lines of sight and objects competing for attention.

By the time he was back in Australia Williams had also adopted a 35mm reflex camera which allowed for closer focus on the foreground subject and more random framing. The new mode and mood of his images suited Williams' perception of how different Australia was on his return.

By 1970, thanks to the 1960s mineral resources boom, Australia was a markedly more affluent nation but also politicized by the debate over participation and conscription for the Vietnam War. The latter had brought thousands of American soldiers on rest and recreation leave to the major cities and their presence had generated a new interest overseas in publications on Australia. Williams was appalled to find a beer-swilling male culture of mateship and 'ockerism' being celebrated and promoted as part of the national identity.

|

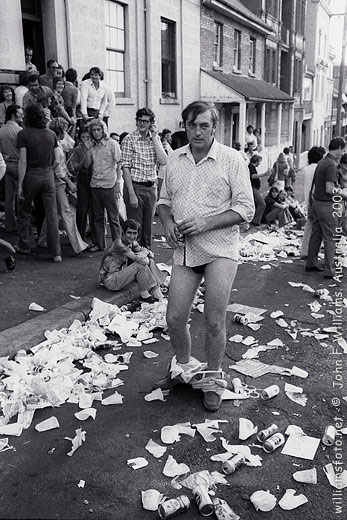

His view of St Kilda Beach in winter of 1975 is effectively a self-portrait in which the bleak grainy image expresses his own sense of dislocation as a 'native' no longer at home and aware of a culture gone awry. In this mood Williams began recording the notorious 'pub crawls' in the Rocks area of Sydney in the early 1970s — a body of work which would attract considerable interest and exposure. To his consternation the images came to be seen as an affectionate look at his compatriots rather than dismay at their philistinism.

More supportive for his future professional career was that photography was poised to become the medium of choice for a new generation. The new photographers were remarkably uniform in their disinterest in becoming photojournalists or glamorous professionals in advertising. Their style and approach came to called 'personal documentary' in distinction to the art-directed, sanitised and simplified magazine photography they opposed.

In 1974 the Australian Centre for Photography opened in Sydney founded largely by David Moore and Wesley Stacey and funded by the new Government funding agency the Australia Council for the Arts. Articulate and experienced Williams was soon sought out and drawn in, and was able to leave engineering work to take on a role as an artist, curator, teacher and writer. His personal orbit was also reset in 1974, when his first marriage ended and a new life began with Ingeborg Tyssen, a Dutch-born nurse also making photography a vocation.

In 1975 Williams and Tyssen moved to Melbourne to establish, with two other Melbourne based photographers, The Photographers Gallery and Workshop in Punt Road South Yarra. Williams taught practical courses and Adult Education appreciation courses. He also began writing reviews for The Australian in 1973 (continuing till 1977) and later for 12 months for The Melbourne Age from 1975 -1976 and as well became editor and contributor to Camera Graphics magazine from 1971 to 1974 and Photography News between 1972 and 1974.

In 1976 Williams returned with Tyssen to Sydney to become the founding Senior Lecturer and Head of Department in Photography and Film at the Sydney College of the Arts in Balmain. William's work was included in the early Australian Centre for Photography publications and he was one of the first artists to have a solo exhibition there in 1975. Later he was also included in the Philip Morris Arts Grant collection and his works were acquired by curators in the newly formed photography collections at national and state galleries.

In these intense years Williams produced bodies of work which continued some of the classic rather wry vision of people and their environment of his European reportage mixed with an edge of the new sharper personally inflected documentary style. They also have an ambiguous alternation between pure formalism and social documentation in line with a prevailing aesthetic of fascination with form and space in contemporary photography of the time.

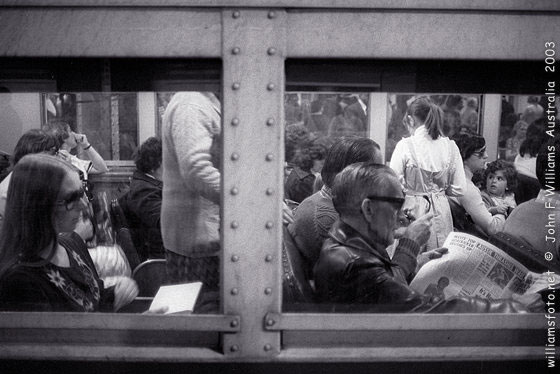

His subjects in late 1970s seem engulfed by signs and slogans, concrete and rubbish. Old people appear as being invisible to the young, looking lost in their own world and often merely glimpsed in reflections. In Williams' 1976 series on the Sydney underground rail for example, the background becomes a disintegrating and unstable environment with splayed forms and split images.

Using a 35mm SLR with a perspective-control lens at waist level, Williams also went into the street to capture a child's-eye view of a slightly bizarre adult world. No one pays much attention to the camera or each other. Williams shows instead a pervasive emptiness in which the ghostly inhabitants on the streets are overwhelmed by clutter and the museums are vacant palaces of culture.

In the 1980s Williams took on board the critique of naturalism of the post modernist theoreticians and their scepticism about the ability of documentary photography to be a meaningful form of reportage. He began to show the role of the camera and photographer but also the 'past' beyond the moment of exposure in a very different body of work using multiple images. (The panoramic works from this series are to be the subject of a future publication).

Williams also flagged his growing attraction to historical constructions and myths with images from his own family album which he inserted into modern day views often of the same location. Thus the photographer himself appears in his own work in short and long pants defying the time restraints of photography as generally perceived. A body of work specifically about his father's experiences in World War I evolved into an exhibition held at the Historial de la Grande Guerre in Péronne, France.

In the late 1980s and twice more during the 1990s Williams and Tyssen had residencies in Paris at the Cité des Arts. By 1988, deliciously and contrarily in face of the excesses of nationalist fervour and identity seeking during Australia's Bicentenary, Williams was at work on a doctoral thesis on cultural regression in Australia after World War I.

His language skills were revived and his research interests focussed more and more on the period and popular perceptions and myths about World War I. In 1989 a retrospective of Williams' work from 1958-1988 was mounted at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney and marked a crossroads in his career. By 1994 having been awarded his doctorate of philosophy in modern history, his early retirement from teaching facilitated a new career as an author of historical studies of the first half of the 20th century. His research frequently involves the interpretation of images and his own work as a photographer continued in tandem, but no longer in the foreground of his professional life.

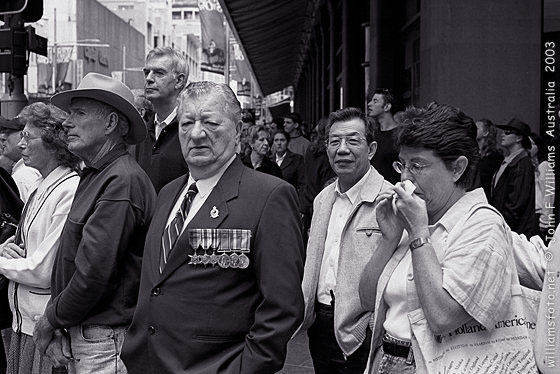

Over time Williams' disquiet through the 1970s at the cultural health of the nation by comparison with that of Europe waxed and waned but mostly found new fuel in each decade. Yet it is interesting in William's more recent works to see the certain changes when he revisits earlier genres such as the old ladies and the old soldiers and passing parade of the urban world.

People are back on the streets in the 1990s and ironically, the ideal of racial harmony promoted by the Family of Man exhibition appears to be effected in modern Australia, in ways never anticipated under the rabid White Australia immigration policy of the post-war years. Now young Asian immigrants and the children of former enemy nations mingle on the corners as the old soldier generation looks on.

Thus, John F. Williams photographer and historian has a history or two of his own and an acute sense of 'history' and the amnesia to which that discipline is prone. While his place in Australian photography since the 1970s is undisputed, full appreciation of his significance and the depth of his whole career, has been short-changed.

After a decade in which as Dr John F. Williams historical publications have been his passion, this survey of photographs from the late 1950s to the present brings Williams the photographer back into view.

---------------------------

John died in Hobart in July 2016

click here for my piece on Clovelly 1964

Click here for more on John Williams

more Essays and Articles by Gael Newton AM

|