Building the Art Gallery of NSW photography collection

The Sydney Camera Circle arrives in a car-boot

Gael Newton

Based on a 1978 letter to Jim [probably Jim Coleman editor of Australian Photography magazine]

about the beginnings of the AGNSW photography collection

Although Harold Cazneaux among others called for the Gallery to accept photography as an art, the photography collection as such did not begin until the acceptance by Trustees of a gift of 90 photographs from the Cazneaux family in late 1975 (following a project show of Cazneaux's work).

At the time photographs were under the care of the Department of Australian art. In 1976 a proper policy for photography was put to Trustees and I was given charge of the new area. The policy was to collect mostly Australian photographers' work.

Indeed what had led to the formation of a separate policy was my proposal for purchase of the first non-Australian photograph, a Frederick Evans platinum print that I found in the Cazneaux family collection.

At that time Trustees felt we should properly consider where the collection was going. We bought the Evans. Little did I know at that time that within a year we would have 15 Frederick Evans' as a gift!

As I was in charge of the collection I decided to start working on Cazneaux's era to determine whether he was the best of his contemporaries or not. With the Help of Rainbow Johnson, Cazneaux's eldest daughter, many relatives of the older photographers were located.

We contacted George Morris's widow and found wonderful bromoils and bromoil transfers of Sydney and places he had visited on his world trip in 1936. Many of these made with a Leica as Morris had been among the first to take up this camera. Perhaps because of his overseas experience or his work as a commercial photographer - illustrator Morris' work shows an almost documentary feeling, for a place.

This becomes obvious when several pictures of one place are grouped together as with his pictures of Polperro in Cornwall where we see the fishermen 'Waiting for the tide' and then coming in with 'The catch’. Extended 'essays' of this nature were rare in Pictorialism, Cazneaux's Sydney coverage between 1904 and 1924 being one of the few other examples but a more ambitious example.

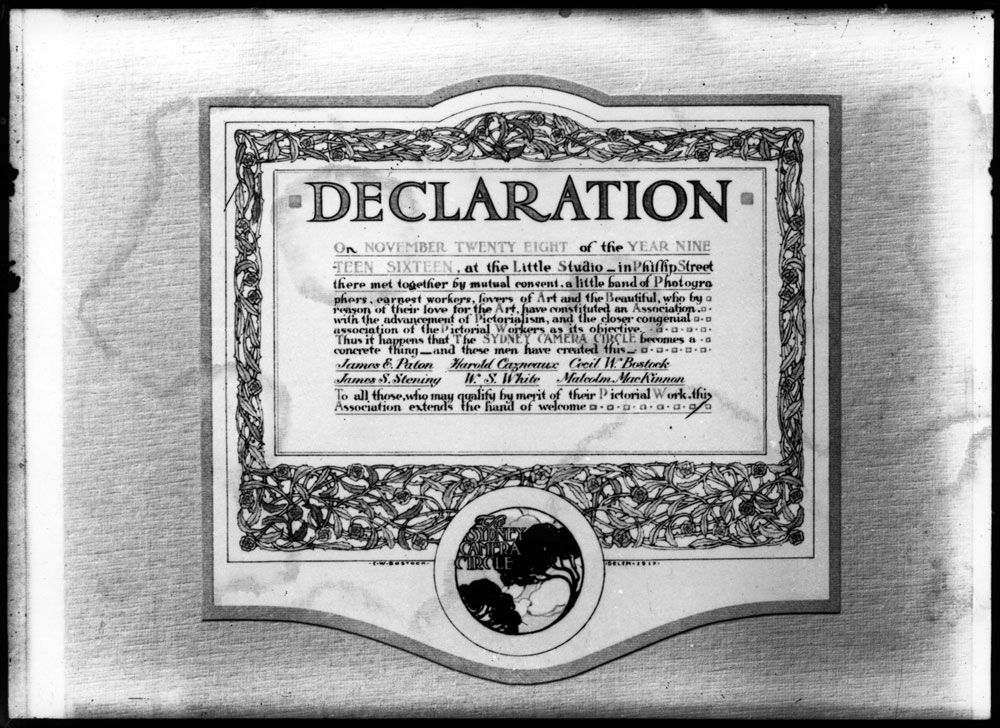

Among Morris's papers were also books bound by his friend and fellow commercial illustrator in photography, Cecil Bostock but the most interesting find was the original "Declaration" of the Sydney Camera Circle which Cecil Bostock had designed and drawn up in 1916.

Bostock was a foundation member of the Sydney Camera Circle and Morris joined late in 1925. Both men were talented craftsmen (Morris designed medals as well) and decorative graphic artists. Bostock's watercolours were also among Morris’ collection due to a rather sad set of circumstances.

Bostock was a difficult man– irascible and erratic! He would invariably be late for any arranged meeting no matter how firmly the date had been set. He was moody and rather contemptuous yet never quite organised himself into the company he might have found more congenial.

He died of cancer in 1940. By that time his marriage had broken down and he died in debt.

George Morris went to the auction of his studio effects to acquire some things for himself and for the Sydney Camera Circle collection. Bostock was a contradictory man in his work as well as his personal manner. His artwork was decorative and colourful– his photography was very pure and straight for a pictorialist.

A man of his graphic talents could certainly have coped with the romantic atmosphere favoured by early pictorialists and his craftsmanship would have led him to excel in bromoiling. Yet his work was usually 'sharp focus' and low key when it came to sentiment, drama or any of the other indulgences favoured by that era. In 1917 he produced 'A Portfolio of Art Photographs’– a hand bound album of ten small photographs in a limited edition of 100. The images are so subtle that they are easy to overlook and dismiss with the exception of the nude that is the best I have seen in the Australian pictorialists’ work all told.

Just before his death Bostock embraced the new large glossy prints of the younger generation. One that he exhibited at the '150th Commemorative Salon' in 1938 was purchased for the Sydney Camera Circle collection and came to the gallery when the Circle's collection was acquired in 1977.

Bostock's studio was also where Max Dupain started his working career. Dupain recalls that Bostock was a perfectionist in technique even weighing his chemicals to literally the last gram. In Dupain's views there was not much more to Bostock’s work than technique. However he may well have been before his time in realising that photography could be an art by being true to its own qualities not necessarily having to imitate the appearance of traditional arts to gain acceptance.

His own promotion of photography as an art all through his life is without question. Even in late life he joined ‘The Contemporary Camera Groupe' showing that his commitment was to the medium not just a particular style in this he could have been more liberal minded than Cazneaux.

The finding of the 'Declaration' of the Sydney Camera Circle, and work by two important members, led to even greater efforts to represent all important members. As it had been an elite group of pictorialists any members should have been good photographers.

Mrs. Johnson suddenly remembered the existence of the 'Sydney Camera Circle Collection' of photographs by Australian and overseas pictorialists. With amazing persistence Mrs. Johnson contacted the current secretary of the "Circle" and discovered that the collection was not with them and was only vaguely remembered.

Re-reading of available minute books in the Cazneaux collection and 'The Current Circle's confirmed its existence; the overseas examples having been provided by a single gift by F. C. Tilney (an English photographic critic) of his personal collection in 1927. Further the collection had clearly been turned over to Robert Nasmyth in the 1960s as custodian.

Mr. Nasmyth was contacted and turned up one day with the boot of his car full of mysterious brown paper packages. All this was turned out on to the lawn of Mrs. Johnson's home and given over on the spot to Cazneaux's daughter to distribute, as she felt best. Mr. Nasmyth seemed disappointed that so little interest had been shown in the work in modern times and disappeared declaring that he never wished to see the stuff again.

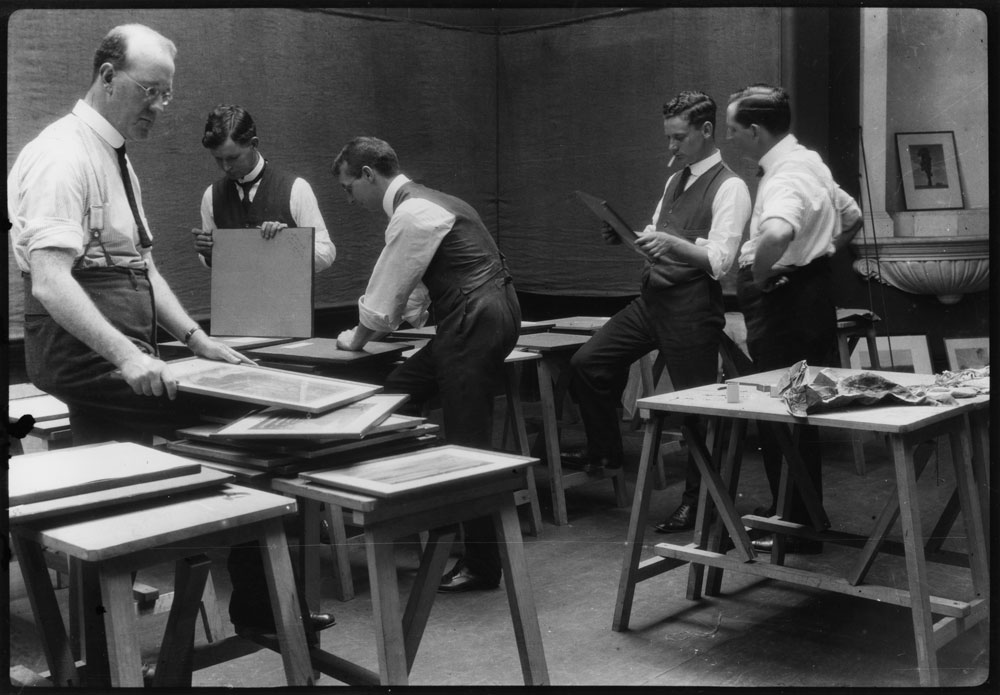

An ecstatic day (for a curator) was spent unwrapping packages and exclaiming over the contents as each new discovery was made.

'The F. C. Tilney Collection' was intact in a beautiful, hand tooled leather box – the work of Cecil Bostock. It contained over 60 mounted photographs the most exciting of which were the lovely platinum prints of Frederick Evans and early experiments with oil pigment process by Robert Demachy. Many names familiar from issues of 'Photograms of the Year' were included.

Tilney was no Stieglitz in thought, action, or collecting tastes. Much of the collection was examples of the discredited aspects of Pictorialism but at current prices the Evans alone were well beyond the Gallery's small budget for photography purchases and could never have bean acquired under normal circumstances.

As well as the Tilney collection, there were photographs by many members of the Circle over the years as well as miscellaneous foreign prints –notably one by Leonard Misonne.

Accessioning of the Sydney Camera Circle collection took some time. Finally an afternoon tea party was held in 1977 to celebrate with all the donors and supporters. By this time contact had been made with two early members, Norman Deck and Stanley Eutrope, as well as the families of Bostock and William Moffitt. Work by all three added to the collection. The collection had grown almost overnight into a quite respectable established area within the Gallery.

During much of 1977 I was overseas studying Pictorialism. I spent sometime searching out Tilney in his hometown of Cheam only to discover a local man also researching him as a local history project. Needless to say Mr. Hallam and the residents of Cheam were amazed that someone had come all the way from Australia to look up an old resident. Mr. Hallam and I exchanged notes on Tilney who turns out to have been quite an unlikeable soul and very pompous.

Tilney gave up photography in the late twenties when he disposed of his collection to 'the Sydney Camera Circle' for whom he acted as a paid critic of members work sent to the Annual London Salon and Royal Photographic Society exhibitions. He was the author of several books on photography and had a great gift for words but terribly reactionary ideas.

Most of the last part of his life was spent campaigning against the international plot to establish modern art and ruin the world. Picasso was his pet hate and a pamphlet against modern art he wrote depicted a monster drawn in the style of Picasso's 'Demoiselles' slobbering over the slain figure of 'Beauty and truth' with a sickle in hand.

With the exception of Evans and Demachy, Tilney's collection missed every other pictorialist we now value–the work of the Photo Secession for example. Fortunately we were able to purchase a copy of 'Camera work', Alfred Stieglitz's avant-garde journal of Pictorialism from the Cazneaux family.

It appears that this is the only copy of 'Camera Work' to have ever come to Australia. It is an issue of 1909 but may well have not reached Australia until 1917 as someone has drawn a sketch for a motto for what appears to be 'The Sydney Camera Circle' in the back cover. As Bostock went on war service to Europe he could have brought it back with him. The issue of 'Camera Work' contained exquisite photogravures of nudes by Alfred Stieglitz and Clarence White.

By the time of my departure for overseas a large number of the names of the pictorial era were in the collection. Attention was then given to the next generation around Max Dupain whose work had been acquired in 1976. Using two faithful but dog-eared copies of ‘Australian Photograph 1947’ and ‘1957’ contact was made slowly with the 'moderns’. This was a satisfying exercise as most photographers were still alive for a start and the work was more to our contemporary taste. As I went from person to person I became a messenger pigeon.

Photographers who had lost contact with colleagues sent messages to old friends. It became obvious that another party had to be held.

On October 7th some 30 photographers assembled at David Pott's house in Woollahra. Athol Shmith and Wolfgang Sievers were among the Melbourne contingent. Max Wilson and David Moore fortunately brought their cameras and even stayed sober to take pictures. A favourite of the evening is one of Russell Roberts, Laurie Le Guay, Max Dupain, David Potts in the kitchen representing between them over fifty years of photography in Australia.

By 1978 enough work had been collected for a survey show of Australian pictorial photography that will be held in June this year. Some photographers are still unrepresented notably N. W. Appleby.

Next year it is hoped to do a sequel show covering modern photography to be called 'Photographic Illustration 1920-60' covering the post war generation. Anyone with any prints or information on Pictorial photographers is most welcome to call me at the gallery.

for more of my Essays and Articles (click here)

|