Tracey Moffatt: Cover Girl

Gael Newton

Originally published 1995

What's in a name? When I was a teenager in the sixties Australian girls didn't often have names like Cindy, Jodie, or Tracey. There was, however, a noticeable fashion for these American-style names for babies. No doubt some of these babies grew up playing with the new super-feminine 'grown-up' dolls; the blonde Barbie (born 1959) and her friend Cindy.

As a child in the sixties Tracey Leanne Moffatt named her black baby doll Cindy. (Cindy can be seen in Doll Birth 1972.) Moffatt's own dark hair and good looks are from her Aboriginal natural mother. Perhaps her doll's name referred to Cinderella, whose tale of transformed identity from pauper to princess had been given the Disney treatment in 1950. Role models for brunettes were few in these decades, and for non-Europeans, practically non-existent.

Several decades later in the 1990s Tracey Moffatt is a successful independent filmmaker and artist/photographer whose work involves remodelling the images and stories of her youth. She is one of a remarkable generation of women photographers who graduated from art schools in the early eighties and announced their presence with confident, stylish and attention-seeking works.1

From time to time Moffatt casts herself within her films and photoseries. In the Something More series of 1989 she is an exotic Suzie-Wong-from-the-sticks, an erotic muse in Pet Thang from 1991, Ruby the haunted young Aboriginal mother in her 1993 feature film Bedeviland most recently the daughter/victim of Mother's Day tensions in Scarred for Life. Now especially for the cover of this book Moffatt appears as a sweetly old-fashioned suburban teenager but with the wholesome sexiness of mouseketeer Annette Funicello. So who is Tracey and what is she doing in remaking the images which made her?

Moffatt was raised as a foster child with a white family in a working-class suburb of Brisbane, capital of the tropical north. 'Not very stimulating' is Moffatt's comment on her home town. Cultural diversity, gay rights, feminism and issues of Aboriginality arrived somewhat later in Queensland than in the southern states. Any sense Moffatt had of the possible identities denied to her by sex, class and racial background was countered by the delightful fantasies and energy of popular culture. Despite being short on role models for anyone other than white men,2 television, films and picture magazines gave Moffatt her space to dream and the material to work with in her career as an artist.

American critic Charles Labelle sees such a relationship to the media as a distinctive feature of Moffatt's generation, as a natural resource for their art:

If you were born after 1960 then probably a good percentage of your childhood memories come from television or movies. You may never know if a particularly sacred image has its origins at a family picnic or in an episode of Lost in Space. And does it matter? Is a memory taken from a film any less real than one derived from a 'lived' experience? Are the feelings it evokes felt any less.

The question, strangely enough, is (to bring up yet another film) at the heart of Blade Runner, in the scene where Deckard reveals Rachel's memories to be transplants. The inference is that stripped of our memories we are deprived of our humanness, our identity. Yet, by its end, Blade Runner pointedly suggests that, in a sense, all memories are implants of one sort or another, rootless images whose relationship to the 'here and now' is in a state of continual reconfiguration.3

Picture stories and photodramas of magazines and television attracted the young Moffatt to film and photography. As a child she developed a directorial enthusiasm for snapping her family with a Kodak Instamatic and a home movie camera. Fortunately for her career both film and photography had been introduced as serious creative disciplines in art schools and galleries in the seventies. Yet the photography the young students of the late seventies and early eighties aspired to was fundamentally different to the kind of 'personal documentary' style4 taught the previous decade.

The new generation of eighties artists distrusted naturalism and the camera's claims to truth and had what film critic Adrian Martin calls 'an almost reflex phobia for any form of aesthetic realism'.5 They did not want to be reporters or observers but clear constructors of their images. They frequently embraced staged tableaux, artifice and kitsch, as well as past art styles and iconography—often all in the same picture.

Influenced by new theories of the way all images are systems of representation and power, young artists also shied away from classicism, formalism and notions of the romantic artist expressing a unique vision. If anything they did not want to be original, pure, or true to one cause. Rather than the decisive moments of master documentary photographers like the Frenchman Henri Cartier-Bresson, the new generation preferred the labyrinthine mediations of French cultural theory. Moffatt, who mainlines her memories directly from the visual media,6 found the new theory and taste for constructed imagery well suited her personal experience and inclination to re-envision histories.

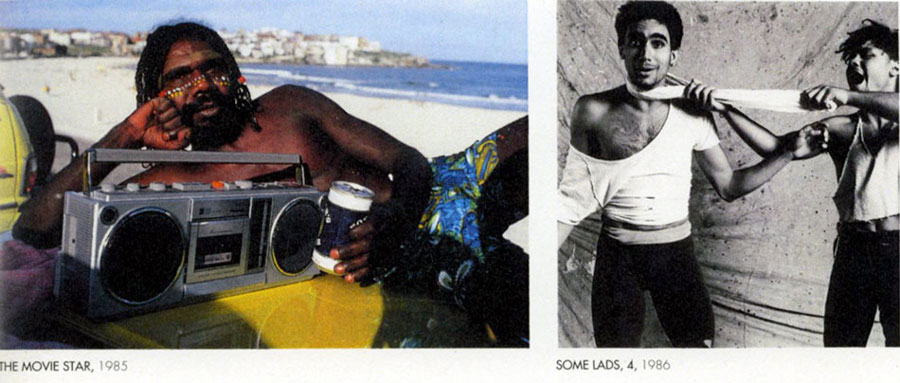

After graduating from the Queensland College of Art in 1982 Moffatt moved to Sydney and was engaged in making a number of zappy short films for Aboriginal organisations which mixed animation, graphics and straight footage. Photography was at this time an activity between film projects. Her first photographic works to attract attention were portraits shown in Sydney in 1986 in a pioneering exhibition of photographs by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists. The show included Some Lads, a series of seemingly direct portraits of Aboriginal dancers in classic black and white prints and a single lairy colour portrait of the young Aboriginal actor/dancer David Gulpilil, star of the 1971 Nicolas Roeg film Walkabout.

Moffatt photographed Gulpilil in bright coloured board shorts at Sydney's famed Bondi Beach promenade lying across the bonnet of a super-shiny car. Gulpilil lightly clasps a 'tinnie' of beer and grooves to a ghetto blaster. His relaxed pose ironically overturns our history in which sun-bronzed Aussie surfers have displaced the original inhabitants from these shores.

The image disconcerted some viewers who claimed it made Aborigines 'look bad' under the assumption that booze and good times were always a disastrous combination for 'blacks'. Amazingly the image was described as a 'candid shot' by one reviewer7 despite Gulpilil's face being painted for ritual dance, a feature bizarrely mocking the zinc nose cream then being urged upon white Australians as protection against sun cancers. As Moffatt said to the press 'It is a typical Aussie pose. Why don't Aboriginals have the right to relax in the manner other Australians do?'8

Gulpilil's portrait also cheerfully rippled the waters of white fear of Aboriginal sexuality.

Was this trendy young man capable of winning the heart of the young English girl in Walkabout?

Some Lads was the collective title Moffatt gave to the portraits of the dancers in the Aboriginal and Islander Dance Company. Moffatt had already played with words in titles for her films like Nice Coloured Girls but henceforth the concepts embedded in titles became an inseparable dimension of her works. The title recalled The Likely Lads, a popular British sit-com about working-class young men in London. Some Lads is an attractive and energetic series showing the vitality of the dancers but it also proceeds by a series of visual double meanings playing against the perceived image of urban Aboriginal men.

One dancer with reggae dreadlocks and a T-shirt rolled like a guerilla bandolier slung round his chest, nevertheless strikes a pose from classical ballet, another flexes muscles like a body builder, yet another pair horse around. For Australian viewers the mock lynching shown in this image had a sinister overtone. One of the horrors of these years was the growing recognition of the numbers of young Aboriginal men in gaols being bashed or committing suicide by hanging themselves.

Sexuality is often neutralised in dance photography but here, as in the Gulpilil portrait, the dancers' bared torsos and loose practice clothes raise the issue of Aboriginal male sexuality and their attractiveness to white women. The subjects are dancers, and they are Aboriginal, but the neutrality of dress and setting extends their image beyond the popular equation of all-natives-dance-in-corroborees.

In banishing artefacts, body paint and Aboriginal references from the Some Lads series (the company performs a wide range of works not necessarily with traditional motifs or costume) Moffatt was consciously countering the patterns of the colonial ethnographic photograph. In particular she was aware of the studio portraits of Aborigines made in the 1870s by the German immigrant photographer J.W. Lindt. His studio tableaux were seen as truthful and scientific representations, and were widely distributed well into the early twentieth century. A notable feature of the Lindt portraits is the passivity and blank eyes of the subjects as they play out a fantasy of active tribal life for the camera.9

In the portraits of the dancers in Some Lads, Moffatt chose a simple paint-splattered backdrop and side lighting with a feel of daylight. These features echo the painted backdrops and top lighting of nineteenth century studio portraits as well as the contemporary fashion for severely neutral backdrops made popular by the renowned American portrait photographer Richard Avedon.

The Some Lads prints also showed Moffatt's own technical sophistication. The tones of the prints are rich and sensuous. The backgrounds are quite beautiful with their artfully arranged folds and gathers providing the kinds of dynamic diagonal sweeps which reappear throughout Moffatt's later works. There is also a quiet statement by the artist in the formal strength of the portraits; a kind of 'well I can do all that classical stuff.

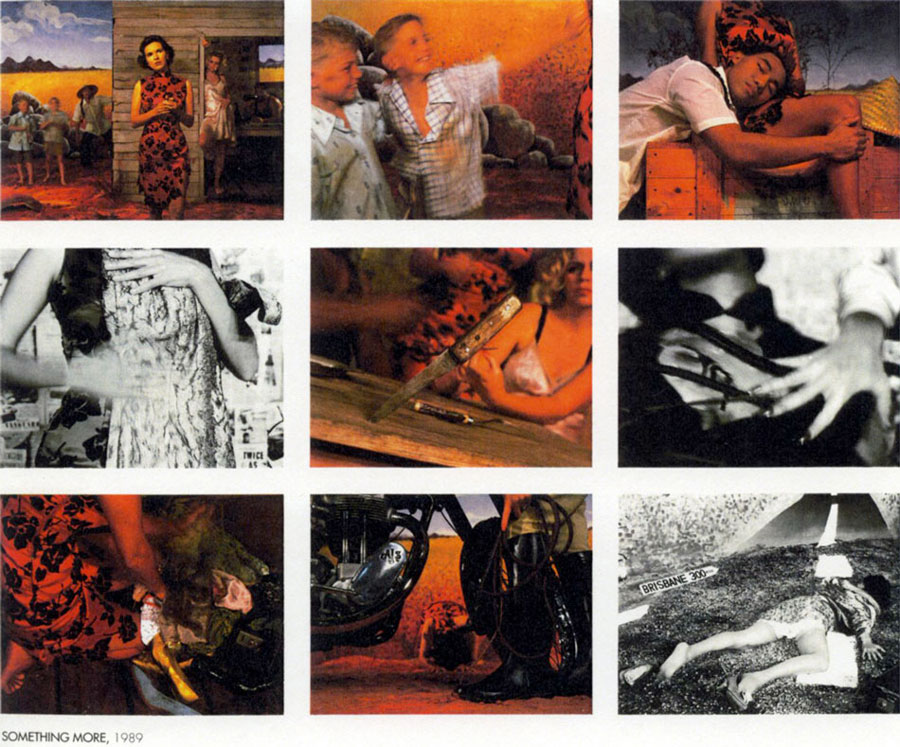

Something More was Moffatt's next work and the one which established her modus operandi as a director of photo-narratives and her status as an up-and-coming artist who was Aboriginal, and a woman, but was not to be typecast as an Aboriginal woman photographer. The series was made during a residency at Albury Regional Art Gallery in a southern New South Wales pastoral centre. It is a clear fiction and was produced in the manner of a film using props, extras and crew.

Something More proudly wears its sources on its sleeve, from old movies, torch songs and soft porn to the folk stories swimming around any society. A young country girl of mixed race aspires to 'something more', perhaps even the role of the bottle-blonde screen goddesses in satin. In the subsequent eight images of the series our heroine spurns her place geographically and metaphorically, is abused, abased, thwarted and finally lies dead in stockings and lame dress on the road to the big city. Whodunnit? We don't know. Although the clothing suggests the fifties, the story could be set in any remote society with mixed races and outcasts at the peripheries of power.

Often characterised as looking like stills from some film now lost, so that we must reconstruct the story from fragments, the nine images (six in colour and three black and white) are more like photographs of the local theatre company's performance of some play about desperate lives in the hinterlands. The cinematic quality arises from the frequent inclusion of blur and frozen motion as well as rather claustrophobic low angles and close-ups. These strategies impart a voyeuristic intimacy with the heroine who is only shown from the neck down after the initial frame. This impersonality is appropriate as each image collapses an already deeply familiar tale of the Fallen Woman, the illegitimate one, the Cinderella who doesn't get to the ball.

.

In the opening image we are compelled by the vision of a fresh Eurasian/native beauty in a luscious red satin cheongsam. She is well groomed and made up with red lipstick and nail polish. Her dress, however, tells tales on our would-be glamour queen. The tattered hem shows it is secondhand. She takes a tentative step forward, lips slightly parted, eyes raised toward some distant and uncertain goal.

She clasps some object or talisman (actually a pair of sunglasses) in a gesture of prayer. Colour, gesture and symbols clash. The girl is both virgin, whose symbol is the rose (even if shown here in black on the dress), and whore at the same time; Eve destined to fall.

The young hopeful is watched by a frowsy older woman whose over-red lips and creased satin chemise proclaim her as white trash. Her mouth is shut tight round a dangling cigarette and the fading peroxide hair is showing its dark roots. She has closed her false-lashed eyes against the hopeful view even if she still clings to the trappings of glamour. The boozing Aboriginal man inside the shack watches with a smirk. Are this couple the parents whose demeanour suggests their hope that the young woman will fail and thus confirm their own hopelessness?

A young Chinese man springs from behind the shed. His love relationship with the girl is confirmed by the later image of him shown clasping her knees in hope of holding her back, but her upright stance shows clearly—She's leaving town. Two small white boys in shorts make a flurry on the left, seemingly jeering and slow clapping the fantasies of the young woman who wants to move on.

The opening scene of Something More is divided in three like an altarpiece with its six figures deployed on different planes and each inviting examination in turn. The complex directorial decisions as to placements, props, lighting, colour, focus and framing can be overlooked in the seemingly naive set. It is not to be dismissed as the merely functional set for some melodramatic stage play. The image enthrals us because it is so deliberately constructed.

Each feature plays its part, beginning with a flourish of fat white painted clouds which unfurl against an intense blue sky fading to mauve at its junction with inhospitable blue hills. A field as gold as the leaf of some icon then dominates the middle ground until it meets a carpet of raw red soil at a line of jagged rocks. If there is a Biblical analogy to the Promised Land here, it is also evident that this desert land has been made productive with hard labour, but the profits of this labour are taken by others not shown in the scenario.

The colours and styles of painting in the set recall both the great landscape traditions of European and Aboriginal Australian painters such as Arthur Boyd and Albert Namatjira. The blurred motion of the two white boys, which might seem to have been a failure of exposure, plays an essential formal role in the image in attracting the eye and counterbalancing the visual weight of the shed and the three dominant figures on the right. The discarded hub cap and rusted fender in the lower left corner do more than fill a space. These objects are the symbols of the failed journeys and weary returns of other travellers. They recall the old car in which the character played by Jack Thompson returns at the beginning of the 1975 Ken Hannam film Sunday Too Far Away—one of the artist's favourite films.

The Something More series can be viewed as a lineal sequence or a grid of images. After the rush of lush colour and elaborate details in the first three images, the dress alone appears to carry the narrative as the young woman resolves and struggles to depart. There follows an abrupt lurch as the narrative switches to a blurred close-up image in black and white in which the young woman is being whipped or violated.

The next image, the most still and ambiguous in the series, reveals the oppressor to be a woman bikie with long red nails. The image is full of lustre, from the woman's red lacquered nails to her polished boots to the gleam of the showroom-shiny chrome of the vintage AJS bike. Its sadomasochistic character has been forecast by the bolding of the S and M title letters in the original catalogue for Something More. Its message leaves many questions in its reference to the notion of the complicit victim and the pleasure of pain.10

The high camp melodrama of the bikie image skates close to making the viewer suspect it is their own gullible appetite for melodrama and titillation which is being sent up. It is also the point at which the narrative ruptures. After this fall or supplication, the young woman is recast as fugitive and victim.

She reappears inside the shack holding a lame dress. In the background the 'wallpaper' of old newspaper advertises radios, a reference to her media-driven desire for the goods and status but also suggesting the litany of pop, blues and country and western songs which reiterate the tale of the Fallen Woman.

Clearly the dress, along with the high heel shoes, have been stolen from the suitcase shown in the next scene. Perhaps these are relics of the former lives and aspirations of either the bikie (who has been transformed and survived as an aggressor) or the older blonde mother figure (who has survived by accepting a lesser role). We don't know. Neither do we know which nemesis slays the young woman on the road leading to the far away 'Big City' of Brisbane. Who takes the slippers from Cinderella and to what degree is she complicit in her own fate? There's no prince, no fairy godmother.

The pathetic ending to the tale of the Fallen Woman in Something More apparently only confirms the fates doled out in folklore to transgressive females and 'bad girls'. Moffatt appeared to be saying nothing had changed for women if you were not part of the liberated white middle class and expressing some of her own suspicions and uncertainties about the sudden fashion and acceptance of contemporary Aboriginal artists in these years. From this point on Moffatt would not permit her work to be shown or reproduced in exclusively Aboriginal or 'black' artists shows.11

In embracing such ambiguous images of women Moffatt shares certain characteristics of the generation of women artists in the eighties whose works hardly fitted the bill as far as positive feminist role models go.12

The influence on contemporary art especially filmmaking, of new psychoanalytical theories about the therapeutic role of old and even misogynist fairy tales13 offers other readings of the incorrectness of 'bad girl' imagery. Writers such as Bruno Bettelheim and his study The Uses of Enchantment: meaning and importance in fairy tales (1976), have led to a rehabilitation of the fairy and folk tale from its discredited association with old wives tales and the kindergarten. Instead there is a view that we must renew and retell fairy tales and myths in order to keep them under control, otherwise they can fade, or like movie monster Freddie Kruger they can grow stronger in their destructive force. Marina Warner and her feminist histories have more positively reclaimed the fairy tale as essentially within the realm of the female narrator.14

From this vantage point Moffatt's revisiting of the folk tale of the Fallen Woman is part of such a process but is also inflected with the perspective of her own time and position. Her formal strategies with their constant reference to how each image and story is constructed also affirms that things can change. We are left with the knowledge that the woman didn't just fall—she was pushed!

.

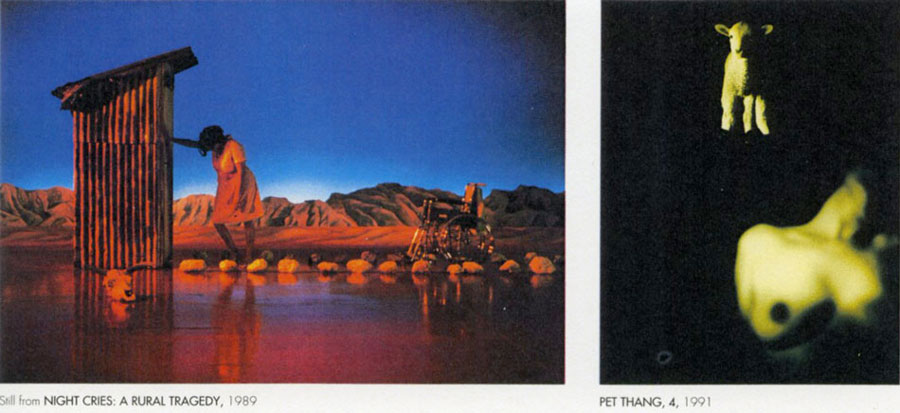

Following Something More came Moffatt's 1989 short film Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy which was also a clearly staged narrative using both the stillness of the photographic tableaux and the action and sound of film. Its intensely painted and coloured sets employed a palette of effects from surrealism to psycho dramas. Only seventeen minutes long Night Cries seemed to subject time and history to a painfully intense compression. It is visual details such as the shiny red 'dirt' floor and the soundscapes which remain in the mind; the creaking door, the old woman's breathing, the scraping sounds of desert wind and shoes. Night Cries is a gloss upon Jedda, Charles Chauvel's 1955 feature film in which an orphaned Aboriginal baby girl is fostered by the white station owner's wife.

Through her later attraction as an adult to a wild Aboriginal, an outlaw from his own tribe, Jedda finally meets her death at his instigation, falling backwards off a cliff. Her intended 'good' young man, an assimilated half-caste, is spurned. The daughters who perish through their unsanctioned desires in Jedda and in Something More are re-imagined in Night Cries as having lived to foster the mother in her decrepitude. This old hag and wicked stepmother of mythic lore and fairy tales here sucks the life from her child with every gurgling rasp. Night Cries is a metaphor of the lost true mother and the political fate of the dispossessed.

After the elaborateness of Something More, Moffatt's second photoseries Pet Thang came as a puzzling change of mood in 1991. Pet Thang presents a naked woman floating in darkness with images of a sheep and a lamb. She is some old goddess perhaps; or a bacchante. The images are too lewd to be linked with the cute lamb of the Madonna. Indeed Pet Thang is not a narrative which invites speculation and completion. Rather it develops a certain suspension and intimacy.

Sometimes the woman dreams, sometimes she appears in bondage or subjection, with sacrificial S&M overtones in the form of a black leather glove. The lamb had Mary, it seems. Attending the opening of the exhibition of this series, I was taken by the seriousness and silence the work received. There are echoes of the extravagant fantasies in surrealist films such as those of Jean Cocteau, yet Pet Thang as a title wafts with the twang and whine of country and western music: 'Pet Thanngg, you make my heart sinngg'. The title is irreverent to both surrealism and S&M. It seems also to mock the political realities of white European pastoral achievement symbolised by the sheep. Yet the series remains genuinely mysterious and elliptical beyond its melodrama.

The currents of Moffatt's work were elaborated in her feature film Bedevil, a trilogy of ghost stories she heard as a child from white and Aboriginal relatives. Bedevil received a mixed critical reaction. It was as if the complexity of the narrative blocked the usual absolute seduction of the viewer by image, colour and sound. Of the film Moffatt commented: 'Perhaps we're all a little haunted in a way and we don't ever come to terms with it.

Why is it a bad thing? We need it—the ghost that haunts us all.15

.

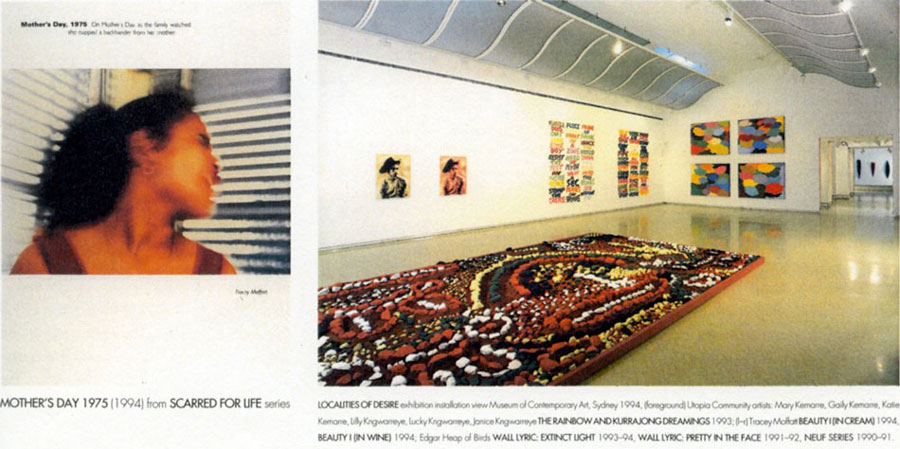

Moffatt's next photoseries Scarred for Life, undertaken during a residency at the University of Wollongong in 1994 was also about being haunted but in real life. The series is constructed as nine separate stories about fateful experiences in early childhood and adolescence. The production of images in the series as a set of photolithographs in muted colours, rather than luscious photographic prints, is modelled on the pages of early issues of LIFE magazine.

Her captions provide the kind of explication of pictures deemed essential in photojournalism. The masthead of LIFE in 1936 proclaimed a desire 'to see life and witness great events' but photojournalism rarely engaged with the individual's battle in early life to establish a self-image. The magazine rarely descended to showing the role of media stereotypes or the way words such as 'you're useless' and 'you'll never' can become a life sentence and extinguish self-esteem. LIFE prided itself on covering real life as well as tragedy and drama, but its middle-class audience did not want to know about sexuality or skeletons of deviance and violence in the family closet.

Some of the vignettes presented in Scarred for Life relate more to the magazine covers of the American illustrator Norman Rockwell, arch priest of wholesome family values. For example, in The Wizard of Oz, 1956 a young boy dressed as Dorothy for a school performance of The Wizard of Oz betrays an incipient enthusiasm for cross-dressing and is summoned before a tweedy old patriarch who pontificates with his rather phallic-shaped pipe. The toby jugs on the fake mantelpiece look on knowingly.

These peculiarly popular ceramics still carry some trace of the lewd knowing winks of the court jester. The characters in the Scarred for Life series mix Aboriginal, Asian and European races but it is the Aboriginal girl who discovers her adoption, the boy who fears he'll never succeed, the violence of Mother's Day and the unknown agenda of a naked man and small girl which puncture the viewer's complacency and any nostalgia about adolescence. The 'sets' in Scarred for Life are, uncharacteristically for Moffatt, from real locations.

Clean rather than chic, the locations are triumphantly suburban in their portrayal of the values of the fifties and sixties. The series title has no sing-song associations. It is bald, a pun upon the association of ritual scarification in tribal cultures and the debased rites of passage of suburban youth as they run the gauntlets of verbal and physical assaults.

In the same year as Scarred for Life, Moffatt produced two images as part of a Beauties series, Beauty I (in wine) and Beauty I (in cream). Beauties was as enigmatic in relation to its precedent as Pet Thang had been as a riposte to Something More. She directly appropriated (rather than re-staged) a fifties studio portrait photograph of an Aboriginal man, manipulating the background to an amorphous cloudy swirl as well as slightly altering the subject's features. The portrait could be a studio publicity shot of some star or performer but the sitter's casual gaze off camera and slightly slouched pose are not the stance of a star. It is an amateur or local effort, not the product of a Hollywood studio.

The man's T-shirt and rakish cowboy hat-come-sombrero suggest he has willingly cast himself as a Latin type. Roles for exotic males were strong in films from Rudolf Valentino on. Like these types our man is beautiful rather than rugged, agile rather than mighty, but he is no threat. We feel he is of slight stature—a man with aspiration but no dreams of his own. The title Beauties suggests references as various as the 1994 remake of Beauty and the Beast and a contemporary interest in issues of masculinity.

The Beauties were first shown in the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney in Localities of Desire, a show about the border zone between regional and global identity.

Moffatt's work grounds the big issues in the immediately familiar and rich role of the exotic male type in our culture as well as the experience of the individual. His story, and whether it is tragic or comic, is not known, unlike that of the native beauty in Something More.

GUAPA (Goodlooking) is a photoseries Moffatt completed during a 1995 residency at Ar tPace in San Antonio, Texas.

Like Pet Thang it is dream-like. The bleached colouration of the ten prints (arising from the printing of the black and white film onto colour paper) recalls the faded magenta cast of old colour film, and the blur and erratic motion of an old home movie. American Roller Derbies, popular since the late thirties and shown on Australian television in the artist's youth were the inspiration for the series. In contrast to the frenzy and hoo-ha of the original events, GUAPA is a curiously sad and silent world. It is as if the soundtrack is turned off with maybe only the muffled and distant sound of wheels left as in the last frame of Bedevil in which boys rollerskate around a carpark.

In the ghostly graphic quality in GUAPA, there are echoes of the punchy graphic effects popular in the sixties, as for example the silhouetting used in the opening for the movie You Only Live Twice and the trailers for the television series The Avengers. These women on rollers (in their strange gear which looks like modern street kids' rap attire), however, come out of ancient myth.

They are tough dames such as once existed in the tales of the Amazons. Bodies fall into the frame or momentarily form a sculptural group. The effect dematerialises the violence of the sport, which was considerable, but there remains the motif in Moffatt's work of violence between the females, as well as encounters with pain. The final image is of a lone figure perched on a rail. She is exhausted, dejected, alone. Has she lost or won? Separated from the herd what is her fate?

Guapa is a Spanish term meaning goodlooking which Moffatt encountered in America when some Mexicans assumed her colouring meant she was one of them. She liked the slightly explosive sound of the word, which is pronounced like 'whoppa'. It is an appropriate term to characterise Moffatt's work as a whole which is always goodlooking, seductive and energetic.

Her works engage immediately, and chameleon-like, tend to take on the colour of different localities. Each group imagines itself and its experience in the scenarios. Despite the predominance of issues of identity Moffatt's work proposes also that visual images and stories which we possess in common by inheritance but increasingly through the global media, are the arena in which futures can be resolved.

Much has been written of the hybrid nature of Moffatt's work and its multicultural references. Such categorisations speak more of an older polarised way of thinking in which something is one thing or another, black or white. There is a long tradition in the western world in which surface and content are seen as inimical rather than intertwined so that the allure of her rich and generous surfaces and scenarios must be approached with caution.

There is often an overtone of anxiety from critics who fear that the strategies at the heart of her practice are somehow threatening to contaminate the whole and thereby sacrifice her progress to a higher realm of fine art. A suggestion lingers that it would be better perhaps if she stuck to one mode, one medium, 'for her own good' so to speak rather than taking the risks she does with her switches from melodrama to tragedy, and from film to photography. This would leave Moffatt herself in need of reading the warning tales of folklore against transgressive females.

We might find it more profitable to take on instead Marina Warner's perspective on the role of the female storyteller of fairy tales and folk stories in her From the Beast to the Blonde.16 The teller of tales must always sense both the prejudices and expectations of the audience and yet exploit the generic openness and constant transformation of the genre. Such a perspective adds new meaning to Moffatt's affirmation in regard to continued work with photoseries that, 'There is still life in photography'.17

NOTES

- Works by some of the emerging women photographers of the eighties can be seen in Helen Ennis, Australian Photography: The 1980s (Canberra: The National Gallery of Australia, 1988).

- The change over the subsequent three decades is sometimes hard to see. White men still dominate rock videos and, as the Guerilla Girls

advertisements have shown, the covers of art magazines. Charles Labelle from his review 'Gary Hill', World Art, No. 2 1995, page 106. Theories and interest in memory has had a particular currency, from fashionable interest among artists in academic studies such as Frances Yates, The Art of Memory (London: 1966) to the more accessible David Lowenthal, The Past is a Foreign Country (1976).

- This term is often used in photohistories to distinguish 1970s art photography which was committed to camera naturalism based on selecting images from the world rather than intervening with staged elements or studio-based set ups. It was considered a more personal, radical and critical vision than that of the photojournalists and documentary photographers of the 1920s-1960s.

- Adrian Martin, page 26 in 'The Go-Between', World Art, No. 2 1995, pages 24-29. This is the most extensive consideration of Moffatt's place within what Martin defines as 'the episteme of radically muddled identity' demarcating post-colonial contemporary art from postmodernism.

- Which is not to imply Moffatt is uninformed or unengaged with contemporary discourses. Language is an integral part of her works. Her most passionate references are to visual images in films and television however literary sources cited include Gaston Bachelard.

- By Anne Howell in her review Tired of the Cliches, Aboriginals focus on themselves', Sydney Morning Herald, 6 September 1986.

- ibid.

- For an example of Lindt's portraits see Gael Newton, Shades of Light: Photography and Australia 1839-1988 (Canberra: The National Gallery of Australia, 1988) page 53.

- Patrick Crogan in his review of the exhibition of Something More at the Australian Centre for Photography in 1989 pursues the issue of Moffatt's violence and argues the work does offer something more, something beyond being trapped into the existing narratives of desire and transgression. See Photofile, Spring 1989, pages 8-9.

- Moffatt was drawn into an exchange of faxes and letters with curator Clare Williamson over her declining to be in a 1992 show Who

do you take me for featuring British and Australian black artists and mounted by the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane to tour nationally. The faxes were displayed as part of the show but not catalogued.

- See Catriona Moore in her Indecent Exposures: Twenty Years of Feminist Photography (Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 1995).

- Discussed in Marina Warner, From the Beast to the Blonde on Fairy Tales and their Tellers (London: Chatto and Windus, 1994).

- ibid.

- Interview in Vogue Australia (June 1 993) page 57.

- Marina Warner, op. cit.

- Letter to the author, 1995.

use the menu below to view chapters of this publication |