INTRODUCTION

This little book seeks to give some vision of the beauty of Australian trees in varied settings. Here are shown forest giants of unknown antiquity, which came to maturity generations before the first white man set foot on Australian shores; also comparative youngsters of recent growth.

Some of them are in remote and seldom-visited parts, others in settings as domestic as a suburban garden. They range from red gums massively guarding the banks of the River Murray to eucalypts giving their scant shade on inland stock routes; from eerie ghost gums of Central Australia among primeval rocks to noble karri trees in the West Australian forests, or casuarinas in tropical Queensland — with, for contrast, graceful native trees adding their charm to parks and gardens of our great cities.

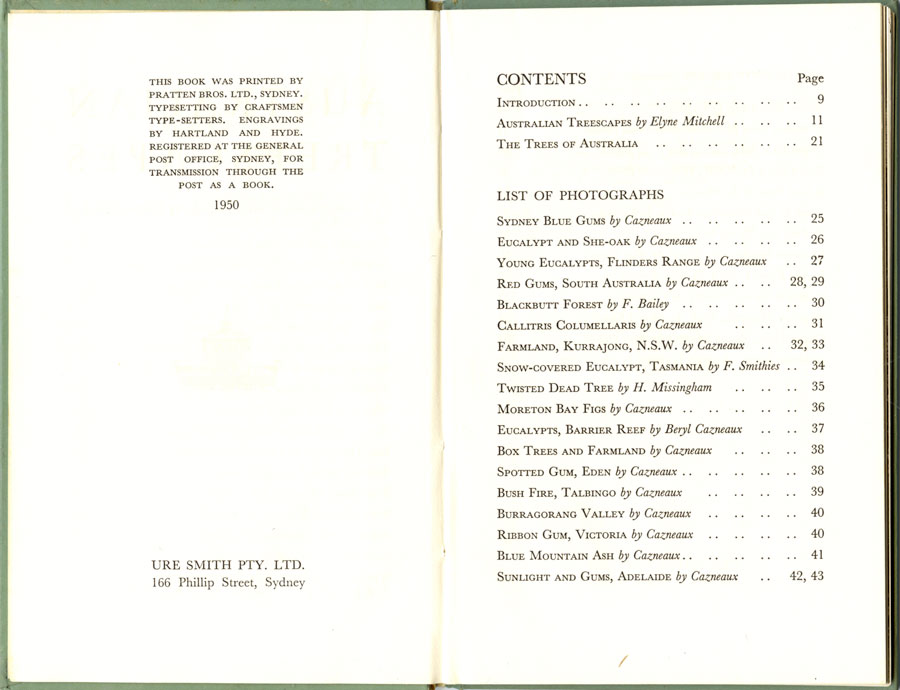

The majority of these photographic studies are by the veteran photographer, Harold Cazneaux. All those who are responsive to the strange beauty and fascination of Australian trees have reason to be grateful to Cazneaux.

Throughout his life this distinguished photographer has made a special study of native trees, depicting them with an artistry that has called forth enthusiastic praise from notable painters.

Sir Arthur Streeton said of him: "The prints by Mr. Cazneaux put all our paintings in the shade. His choice of subject, his splendid instinct for design and light and shade certainly put him as an artist above almost all our painters. No one has represented trees in any way comparable with those in his prints.

He is a landscape man of the first water. He has a great gift."

Hans Heysen, who has perhaps painted Australian trees with more sensitivity and understanding than any other artist, has also written with enthusiasm about Cazneaux' treescapes. Commenting on an International Photography Exhibition held in Adelaide, Heysen wrote: "Cazneaux' * Storm and Sunshine' is truly a beauty. The whole picture is a perfect unit and very convincing – not forced to get effect anywhere."

Member of the London Salon of Photography; the Royal Photographic Society, London, conferred on him the distinction of Honorary Fellow of the R.P.S.

Elyne Mitchell, who has written the descriptive article for this book, is the author of three notable books on Australian country subjects: Australia's Alps, Speak to the Earth, and Soil and Civilisation. Since her marriage in 1935 she has lived on a country property in Victoria, and she has a deep and practical interest in many aspects of rural life.

The Editors wish to thank Mr. R. H. Anderson, Chief Botanist and Curator of the Sydney Botanic Gardens, for his ready and kindly help in connection with this book.

Thanks are also due to the Commonwealth Forestry Timber Bureau and the Forestry Commission of New South Wales.

Acknowledgment is made to the following books from which information was obtained:

Native Trees of Australia, by J.W. Audas;

The Tree Book, by D. G. Stead; and

The Anthography of the Eucalypts, by W. Russell Grimwade.

Editors: Gwen Morton Spencer, Sam Ure Smith

AUSTRALIAN TREESCAPES

By Elyne Mitchell

When I think of Australian trees, I think immediately of the great mountain ash forests with the wind sighing through the hanging streamers of sloughed off bark, and black cockatoos screaming as they fly between the branches; or of the tall white ribbon gums, smooth and straight, that grow with the rough-barked peppermints, and that lovely eucalyptus smell of the peppermint forest is recalled to memory too.

Perhaps I might think of the forest on the Gib – or the ironbarks on the way to the sea from Omeo. Then memory leaps the breadth of the continent, to the huge karris, to the great white trees standing immensely out of a brilliant tangle of purple hovea, of wattle, of coral vine, and clematis. But when I think of the single individual tree or the few, to me there rises an image of a tall, slim, white lemon-scented gum, the graceful citriodora, which seems to contain within itself the whole idea of the Australian Tree.

Many are the single lovely trees, or groups of trees, and many are the forests and woods which seem to me to contain in varying degrees this essence that is Australia which the citriodora holds in its lovely form and about which the truth seems to be even more profoundly told down the wind-whispering aisles between the mountain ash.

All the mountain ash that I know grow in the high mountains — on Mt. Buller, not very far from Melbourne; on Mt. Pinnabar, where their long, long bark streamers lie on the firm spring snow to entangle one's skis and ankles; deep down in the Cracken-back Valley, where they stand on tongues of land between small creeks; on the slopes below the Inkbottle in the Dargals — the great trees in deep, narrow gullies, or mixed with ribbon gum on an open, sunny slope. There is a superb stand of trees at the first bend in Watson's Gorge Creek, looking into that secretive well below Twynam, and Watson's Crags, and the Anderson Ridge to Friar's Alp; then there is Friar's Alp, itself, named by the first of us who ever skied there, because of its snow cap and its tonsure of mountain ash — a magic place in which to rest encircled by the waving tops of the lovely trees.

But the ash forests — the peppermints and ribbon gums, the candlebarks and snowgums — which I most intimately know, are on the Long Spur which is one of the cattle routes from the Upper Murray on to the Kosciusko Plateau. It is there that I have camped often, with and without a tent, ridden or walked, even driven a jeep up and down; there that I learnt that the ash forest seemed to tell me most of the quintessence of Australia — of the immense space of the ancient land that still bears, in all its trees, and plants, and animals, in the earth itself, the imprint of creation and eternity.

I have skied on this Long Spur, with one other companion, when the snow fell through the great high branches, splattering the boles, while we sought shelter in which to eat our lunch; and the wind made a murmuring sound through the leaves and the bark, that told us of our absolute aloneness in miles and miles of mountain forests. In that aloneness came a greater intimacy with the trees and the storm than one could ever feel in a gay laughing company with a warm-lit chalet not far away.

On that occasion our camp was at the foot of the Spur, a little tent moored to a young peppermint and with huge ribbon gums and peppermints all around. Once, high up in one of those ribbon gums, when camped alone with my collie dog, I had seen a black giant flying phalanger outlined against the pale moonlit sky, heard it bark, and watched it take off and glide out of sight in the dense forest.

The top of the Long Spur is above the mountain ash belt and into the snowgum. These are most usually small-trunked trees with twisted, spreading branches, but there is one, where the spur flattens, broad and gnarled, which has been known as The Old Bottle Tree by many mountain stockmen. We have camped not far below it, the tent tied to snowgums with a plough rein, and each night the wind blew the sparks from our fire through the twisted, lashing limbs all around. Yes, it is very intimately that I know the timber of that spur, the rough feel of the ash, the smooth, hard snowgums with their brightly stained, jig saw puzzle bark, their supple branches made to stand up to a great weight of snow, and their thick, leathery leaves.

In many places fires have killed the mountain ash, and the tragic, bleached, grey-white trunks make patches, almost like snow, that break the uniform colour and can be seen for miles. A forest burnt over twice in rapid succession will have no seed in the ground to generate. With only one burning the young trees spring up so thickly that it is sometimes impossible to push a way through. I have come down a spur off the Lyre Bird Plateau, and been forced, because the young saplings were so dense, to run down the great trunks of fallen trees — the road, I discovered, that the wombats used.

Snowgums spring up again from the roots unless completely destroyed, and make a far less attractive tree, like a rung tree suckering. Often they grow in broad bands across the slope, and almost always, in snowgum country one finds lovely grassy glades leading down to a creek or a spring. The dwarf snowgum, like some fantastic tree out of a miniature rock garden, is the highest-level tree in Australia. It is twisted and bent by the snow and by blizzards, sometimes pressed almost flat, sometimes appearing to be espaliered against the rocks.

Four of us once camped on a warm night of late summer in a little circular grove of snowgums high up on Mt. Twynam. A hot wind, forboding bad weather, blew and the moon shone. Moonglow and fireglow played over the wind-dancing limbs of the trees for hours of the night — the dance wilder, the moonlight more silver, the shadows darker each time I woke and looked out from beneath a stretched tarpaulin. Close at hand there was the sound of a creek, and we, it seemed were the sleeping protagonists in some strange rite of the wilderness that had been, or was to be enacted in that snowgums' druidic grove.

One does not often feel that an Australian forest is haunted, not like the deep conifer woods of North America and Europe, but there is one dark hollow on the track to Nurenmeramang where the black sallees grow, their bark so deep green as to be almost black — hardly a tree relieved with the orange that sometimes stains them — and their narrow leaves dark too, while old man's beard festoons the boughs and clusters on the trunks. One is apt to look behind one, there, and wonder if any sound really broke the deep silence, and there, too, one remembers that another people owned and loved this land before us.

The swamp gum, camphora, is another eucalypt that can make a place seem sinister. They, too, are dark in their bark and in their almost round leaves. As their name suggests, they grow in damp places and on the banks of creeks — often with black sallee.

Another wood I have seen that was weird was one just out of Bridgetown in the south-west of Western Australia; it was in a hollow where the early morning mist was weaving, and the trees were big paperbarks, creamy-white trunked, with the paper bark flaking off, and the mist threaded through their soft dark green heads, while, growing in amongst them, too, in great profusion, were tall blackboy grass trees.

I thought the trees of Western Australia were lovely beyond imagination. Not far from this paperbark wood, the giant karris started, and a little further south we were right in the karri country. Immensely tall and straight, they grew, mile upon mile of grey-white trees, sometimes very close together, sometimes more widely spaced with other trees intermingled.

Individually the karris are magnificent; as a forest they are almost unbelievable, and it became a fantasy when clouds of clematis hung about them, or sprays of sarsaparilla, when coral vine twined thickly in the undergrowth at their feet.

The tremendous difference between the karri forest and the forests of ribbon gum and candlebark — also tall white trees though nowhere near as large — is the brightness, the vivid green, of the undergrowth in the former, as well as, in the spring, the bright and lovely flowering of the wildflowers. The Western Australian redgum which grows in conjunction with karri, though it has a bark somewhat similar to our peppermint, is not as grey, and it is the peppermint that does much to give the grey-green appearance to the forests of south-eastern Australia.

I saw one karri being felled and it was, in its way, a terrible sight. We were quite close to it and could hear the splintering and cracking, then the roar of breaking wood; see the huge tree falling through the air. Boughs broke and twisted and flew. Leaves blew as though in a great wind; and all the surrounding tree tops swayed. Almost slowly the grand tree fell; slowly, slowly through the lower trees, the jarrah, the redgums, and the banksia.

Then it was crashing through the undergrowth of purple hovea, the wattle, and the tassel bush; tearing at the ropes and sprays of coral vine and clematis. All the years in which the energy of the sunshine had blended with the water, and soil, and the tremendous power of the seed, had ended. When the forest closed in there was silence. The great tree lay there with the salmon pink of its wood exposed to the light. And it was as though a tragedy had been enacted.

It was many years since I had scrambled through a low-level forest that had no Alps beyond, but here was one containing some of the most beautiful trees I had ever seen, and bright with flowers; that it did not seem to be filled with the same spirit of space, nor live in the same way with the wind and the stars as the mountain forests, was probably due in part to the lower altitude.

Here the hills were low and rolling. One could stand on the hillside, on the slippery red, wet soil where trees had been dragged down to the cutters' landing and railway below, and look for miles; see tree after tremendous tree — the shining wet white bark smooth and hard to touch — see the vivid purple hovea flowering against white trunks, the bright coloured vines and creepers; see the many wattles and the banksia with twisted limbs and long, prickly, serrated leaves, the banksia grandis, whose wood, when polished, has a pleasant, oval grain. All the forest was dripping wet from rain, and the earth smelt damp and warm. Here was the energy of vigorous life — born of the water of a forty inch rainfall, the warmth of the sun, and what looked to be rich soil.

Beyond Pemberton, towards Nannup, were some of the most beautiful karris we had seen, particularly three great trees standing sentinel by a five barred gate. But the country was changing. Already the dark green of she-oak had altered the forest colour, and presently the karri belt had ended and we were in light, red, gravelly soil where jarrah grew and superb wildflowers.

It was outside Busselton, on the Vasse River, near the shining waters of Geographe Bay, that we came on a grove, some acres in extent, of the willow myrtles, low, rough-barked trees, with spreading branches, and soft, drooping leaves; and beneath the trees, growing densely, were thousands of arum lilies.

In the oblique rays of the afternoon sun a golden haze hung over them — the matte, furled flowers and golden stamens — sunlight shone on the leaves, running molten gold.

Between Busselton and Bunbury, in lovely open park land, were the only tuarts I have ever seen; handsome eucalypts that grow tall and straight and have a gunmetal-coloured, striated bark which is smoother than stringy bark. Here they were wide-spaced, throwing long shadows over the soft, green grass.

This south-western corner of the land has been isolated by desert and ocean from invasion by other plants for unnumbered centuries before Europeans came, and its trees and its wildflowers are magnificent. Seeing them was an experience never to be forgotten, and one which made one's wish even greater for the opportunity to learn more of the continent, more of the subtle beauty that is Australia's.

In Western Australia I saw none of the animals that inhabit the forest, and remarkably few birds — perhaps one needs to be camping, or out very early and very late. In our own Eastern Australian forests, the animals and the birds seem part of the joy of it all, just as they are part of the balance of life which makes the forest what it is. I have read that it is most often far up on a ribbon gum, silhouetted against the sky, that one sees the giant flying phalanger.

It is on ribbon or manna gum — viminalis — that the native bear lives. On Phillip Island the manna gums, as they call them there, are not often the tall straight trees that they are in the mountain forests — perhaps it is some effect of the sea — but the bears are there, sitting in the forks, looking down with a serene, placid expression, the most delightful tree-dwellers there could be.

In a hollow limb and trunk of a river redgum in one of our own paddocks, a pair of possums have a two-roomed apartment just on a level to be seen from the back of a horse. We used to call on them regularly with an offering of fruit. Eventually, to our great excitement there was a tiny one who got left behind in the rush 'upstairs'.

There is a theory that possums kept the mistletoe in control, and that since there have been fewer possums the mistletoe has killed many, many more trees.

Wombats are animals we often meet in our wanderings, particularly in the spring when they come out rather early in the afternoon and bask in the sunshine. Below the Long Spur, on the way to Khancoban Falls, there are some fine stringy barks, and it is not uncommon to see a wombat half asleep below one. The holes they dig, generally at the foot of a tree, are enormous.

Lyrebirds build their mounds in the wattle thickets, and can often be seen running through the blanketwoods, or the treeferns that grow down the Geehi Wall.

Geehi is a lovely place for birds, for animals, and for fish — a lovely secretive place enclosed by mountains and forests.

The Geehi Wall is an abrupt drop of 1000 feet, and, after riding through comparitively drab, uninteresting peppermint forest, one comes to it as to a revelation. The ground has gone from below one's feet, and framed by ribbon gums is the great face of Mt. Townsend, and the wall of the Alps.

The slippery track down the Wall winds between ribbon gums and peppermints; great trees and fallen logs; wattle, blanketwood, wild raspberry and bracken. Towards the bottom one clatters down a stony creek bed through the green gloom of a tree fern tunnel with the soft fronds brushing face and hands. It is here that the lyrebirds run through the ferns and call to each other in gay mimicry.

The Geehi flats, themselves, are full of wombat holes and, it is to be regretted, rabbit burrows. In the evening wombats may walk ponderously beside the track or through the little wood of black sallee that grows on a point near the river. These trees have deep orange splashed on their bark.

All round Geehi the wooded hills rise up, and at one end are the Alps, their lower slopes clothed in forest and then the tundra scrub, the snowgrass, and the rocks beyond — or snow stretching right down into the trees; moonlit snow, as I have once seen from a camp in the hut below.

In a day expedition from home by jeep, we once lost ourselves in the forestry tracks of the Meragle State Forest. It was a day on which we kept going, as one does on those occasions, because we did not reach our destination, so there was little or no time to stop and walk through the trees — little time to touch with one's hands the rough, longitudinal striations of the stringy barks, or the clean, hard candlebarks and ribbon gums. There was only time to know that these trees were magnificent ones, only time to appreciate the vivid red summer painting of the candlebarks.

That same summer we motored to Mt. Hotham, over the Gib. From the top of the Gib down, till one reaches the open country round Benambra, there are wonderful trees. Here the candlebarks were bright too, here the young eurabbie blue gums had their blue skirts of new leaves. It was when driving down that way, very early one summer, also, that I first saw clematis in the forest, cascading down the steep hillside like a waterfall. That time we were going to Lakes Entrance and we passed through the ironbark belt — the tall trees rather like a red stringy bark, only each rib of bark is far, far thicker and darker.

Near the Gippsland lakes there were great tall grey box trees that, standing lapped around with a sea mist, seemed somehow a monument to loneliness and sorrow; but bell birds called in the forests and, above the cliffs, in small, spreading eucalpyts, at night, the little yellow flying phalangers glided gaily from tree to tree.

All along the upper reaches of the Murray River, from Albury to Bringenbrong, the eucalypts are predominantly river redgums, lovely spreading trees with grey and white bark — sometimes with a rough knot or two — often fairly short trunked and of good girth, and with huge branches and thick leaves.

Usually the grass is worn away underneath by the hooves Oi stock sheltering from the sun, or there is thick green 'camp' grass growing. One pictures them most, perhaps, in a summer landscape of dried paddocks, a bunch of somnolent Herefords standing underneath, or brood mares, head to tail, flicking the flies off each other's faces and their own rumps, with the little foals standing alongside or lying close at hand.

If I look down from our terrace on a summer evening, over the bleached paddocks, I see these great, green trees that have not obviously changed in appearance since seventy years ago when the first photographs in our possession were taken. Mostly they are along the river banks and round the crescent-shaped lagoons. In winter and spring they may stand deep in water.

Possums find hollows in their limbs and the whistling eagles build their nests in their high branches. I have seen a forest kingfisher patiently sitting on a bough above a lagoon, and then darting down for some small prey that was in the water. Sometimes the redgums seem alive with kookaburras roaring and shaking with laughter.

The wood of the redgum, when cut, is a rich, bright red. For generations the Murray settlers have used it for fence posts on their river flats because it does not rot in water, in fact seems to be better preserved in the damp. It is not only shade for the grazing stock that redgums give, but shade for the travelling mobs too, for the stockmen waiting while the cattle drink.

There are many trees that I know very intimately for the shelter from sun or rain they gave me with the endless mobs of sheep and cattle, trees that have seen many Murray stockmen riding past — apple box, and stringy bark, and forest redgum. How often has one reined in one's horse beneath their shade and watched the sheep drift by? How often pulled a eucalypt leaf and crushed it in one's hand? Even the strong smell of eucalypt cannot entirely defeat the smell of sheep.

There were spring evenings when I would be taking sheep to the wool-shed for penning up, and two or three hundred yards from the shed, the scent of wattle would drift down from the slopes of Mt. Elliot. When I looked up I could see the golden trees; the one ribbon gum whose white trunk stands out of the grey-green bush; the splashes of vivid green that are kurrajongs.

In among the rocks of the hill country there are many kurrajongs with their grey boles and very green leaves. These trees shed their leaves in mid-summer, and the young ones come, shining and delicately green, with a bronze tint, just when the other green leaves and the grass are getting burnt by the heat of the sun. It is not every summer, in Victoria, that they flower, and profuse flowering seems to come quite rarely. The flowers are small, like rounded pale-green bells, the crenellated edges turned back, and inside the throat, there are little purple-brown spots.

The beautiful Queensland lacebark tree is one of the same family as the kurrajongs. The only full-grown specimen of this tree I have seen was in the Melbourne Botanical Gardens. There it stood with its pale grey trunk holding up a head thick with long pink bells which have plum-spotted throats and beneath it the grass was carpeted with the lovely fallen blooms.

One hardly thinks of this tree as a typical tree of Australia because the typical tree is the eucalypt in all its variety — from the red, and pink, and yellow, flowering gums to the wind-driven dwarf snow-gum — but the lacebark tree in flower is one of our most beautiful trees. To come on one flowering in a forest would be even more exciting than to find a green and pale orange tulip tree flower at one's feet in a wood of North Carolina, and to look up to see, high above, the flowering head of the tree.

In forest country it often seems that there is such profusion of superb trees that one does not pick out one and say: "There is the one magnificent specimen". Sometimes they are growing so close together that they do not attain the stature and girth that they might if on their own; this is true of any tea trees I have seen growing many together, but in the Melbourne Botanical Gardens there are two superb trees, one a paperbark with tall, straight, thick trunk and well shaped head, the other a tea tree that has a white flower all over its dense round head so that it looks capped with snow.

For everyone there must be the few individual trees that stand out in memory. There is a beautiful angophora, the rusty gum myrtle, in the same Gardens, but the one I always remember is one I saw near Gary Beach, standing high above a smooth rock, its grey bark stained with pink.

Of all the ribbon gums, there is one particular one, slender and white, alone in a clearing by the "Kosciusko Crossing" of the Geehi River. We have ridden beneath it many times, in winter, with skis on the packhorse, with, ahead of us, the white mountains above the glistening stream, or in the snowlease summer, when the cattle are out in the hills.

In the Nariel Valley there are immense and lovely candle-barks rising singly from the rich paddocks where the dairy cattle graze.

In our garden there is a lovely grevillea robusta — the silky oak that in summer has a head of fuzzy, burnt orange flowers which flares against the deep blue sky. Heavy snow damaged this tree in the winter of 1949, but it is recovering, and at Christmas time we will still have it like a beacon, rising out of the lower garden.

There are two forest redgums that I know which are particularly lovely, one is in our mare paddock; it has a tall unbroken trunk and then a perfect symmetry of branch and leaf. The other, smashed by the snow, too, its beauty temporarily gone into the realm of dream and memory, grows out of the steep hillside below our terrace. It was this tree's branches that I used to watch against the blue of the mountains — motionless branches on a summer evening — and wonder during those War years, whether human endurance could ever become like the serene strength of the tree. And a sleeping magpie would call from somewhere within its leaves, the little bats flit out and in.

The individual snowgums that come to mind are, strangely enough, not living, but dead. There was one, not far from Jagungal, with frozen snow plastered on to it in small rosette shaped flakes so that it appeared to be coated in coral. The other was on Mt. Buller and the dead boughs were encased with ice. The sun setting behind it and the ice glowed golden-red.

I realize, as I think of the dead snowgums, that there are many landscapes in Australia which are simply vast stages for the tragic ring-barked trees. I have only once been in any large area of close-standing huge dead trees, and that was in the Riverina, on the Edwards River. I was a child at the time, but I can still remember the feeling of unutterable sadness that belonged to that place.

The forests of Australia, the lovely individual trees, the quick and the dead — they are something which almost all Australians, whether they are aware of it or not, hold deep in their affections. It was the scent of eucalypt that came, with a sudden rush of longing, when, in Austria with a broken leg, I read a novel of the Australian bush. And was it imagination, or was it real, that faint eucalyptus smell coming off the land when we sailed in Sydney Heads?

It is the eucalpyts that seem to me to be the key to the unusual quality of the beauty of Australia; and perhaps it is because of their soft colours — in their bark, in their flowers and foliage — the dusty bloom over their leaves, that the beauty of Australia is less obvious than that of the Northern Hemisphere to which civilization is more accustomed. For Australia's beauty is sophisticated, subtle, yet primitive, as it 'issued from the hand of God'.

TREES OF AUSTRALIA

Some Brief Botanical Notes

The peculiar beauty of Australian trees was not recognised by the early settlers. Their eyes, accustomed to the lush English countryside, found the Australian bush monotonous and drab, In fact the first artists to visit this country obstinately painted the unfamiliar Eucalypt as an English tree with leaves horizontal to the sun, whereas most Eucalypts hang their leaves vertically to protect them from drying glare, which would evaporate all their moisture.

The subtle attraction of the Eucalypts can only be appreciated by those with observation enough to recognise the variations in their colour and form, their patterned trunks, their scent and their habit of growth. The love of Australian trees comes gradually through association, through the realisation of their aesthetic "rightness" in the Australian scene, of the satisfying harmony they make with their surroundings. It is hoped that this book will awaken a fresh consciousness of our rich tree heritage in this country.

The principal trees of Australia are contained in a number of families comprising about 200 genera and many species. The more important families are:—

The Legumes, containing the large genus Acacia, many species of which are known to Australians as Wattles.

The Myrtles, the chief genera being Eucalyptus, Eugenia, Melaleuca, Leptospermum, Angophora and Callistemon.

The Proteas, which include Grevillea, Stenocarpus, Banksia, Hakea, Macadamia and Orites.

The Pines or Conifers, including Gallitris and Auracaria.

The Laurels, including Litsea, Cryptocarya, Endandra and Cinnamomum.

The Figs, best known of which are the Moreton Bay and Port Jackson Figs.

The Eucalypts are by far the most important trees in Australia, being found in every part of the Commonwealth. The natural distribution of the Eucalypts is practically confined to Australia; apart from a few species to be found in the Austro-Malayan group, the genus does not occur elsewhere, not even in New Zealand or in the islands of the Pacific.

How long the Eucalypts have existed in Australia is not known, but a petrified Gum stump was found in Victoria which an expert estimated to be at least 250,000 years old.

Some Eucalypt specimens were collected by Sir Joseph Banks in 1770, but the first species was described from a specimen collected by David Nelson in 1777.

Nelson was assistant to the naturalist William Anderson; they accompanied Captain Cook's third expedition into the Pacific Ocean. The specimen collected by Nelson was the Messmate or Stringy-bark of Eastern Australia. It was not named until 1788, when the botanist l'Heretier gave it the Greek name of Eucalyptus, meaning "well-covered". This refers to the fact that the flower bud is protected by a little cap or lid which seals the flower until it is thrown off as the bud bursts into bloom and is ready for fertilisation.

A typical Eucalyptus leaf is long and narrow, tapering to a fine point, but the leaves may vary from the almost orbicular or broadly oval to narrowly strap-shaped. Most species have 2 distinct types of leaves which often differ considerably in shape and colour. The juvenile leaves are developed by young seedlings and by sucker growth from injured trees. The juvenile leaves are soon followed by the mature leaves characteristic of the species. Occasionally small saplings may bear both types of leaves simultaneously, and in very few species the juvenile leaves are maintained during the life of the tree.

The flowers are mostly white or cream, but some species from Western Australia have crimson, pink or yellow blossoms, providing a spectacular show in the Spring and Summer.

The trunks of the Eucalypts are very varied, and often very lovely, being white, blue, grey, mottled with red and white and brown, olive green and burnished copper, salmon pink, cream

|