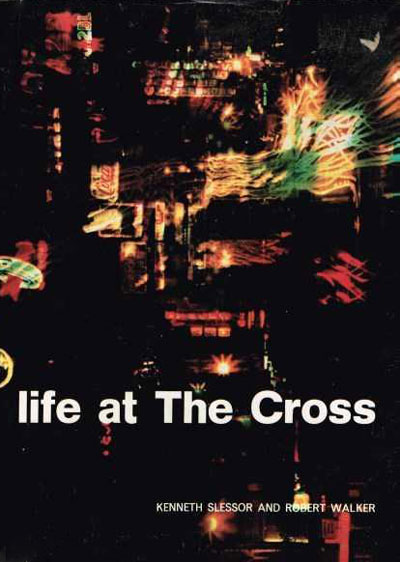

Life at The Cross is a classy tourist-intended publication celebrating the lifestyle of Sydney’s King’s Cross in 1965. It does so with a determined myth-repeating attitude. That is not to say that the book is falsified. What it presents, however, is as much of the area’s reputation as the physical reality of the King’s Cross region. Long-term Cross dweller Kenneth Slessor provides a rather cynical view of the Cross by reputation as opposed to the Cross as home, illustrated by Robert Walker’s widespread coverage of the Cross and environs.

King’s Cross in the mid sixties was a reasonably comfortable Bohemia, according to the book. The gangster era of the Depression is barely mentioned. The immediate post-war reputation as a centre for refugees and other migrants had long been displaced by the general spread of non-English speaking families throughout Australian suburbia. The drug and prostitution sleaze that arrived by the end of the sixties, and is still the area’s reputation, was a few years of Vietnam R & R away.

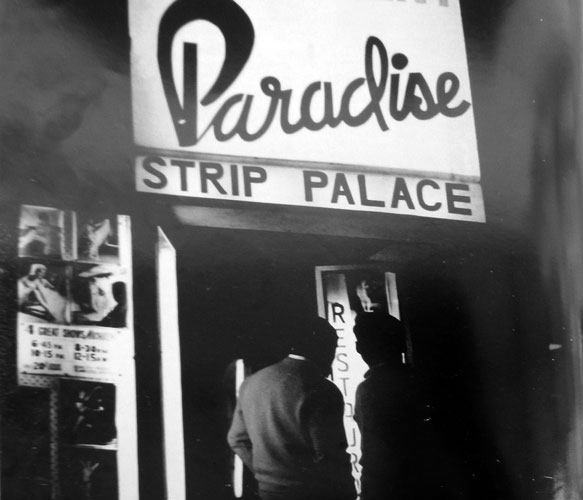

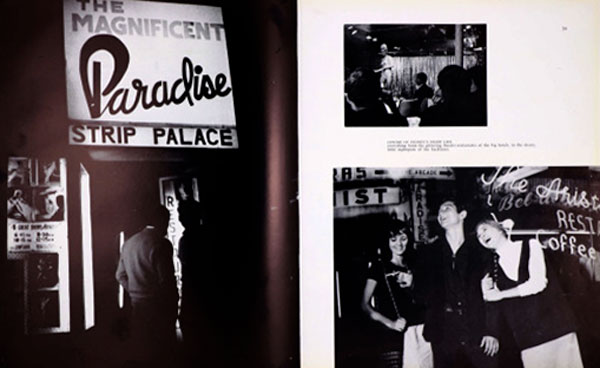

In 1965 Bohemia had a safeness on the verge of wholesomeness by present standards. The main streets are home to the arts, U.S. sailors and the inevitable nightclubs and strip joints. The back streets are depicted as a typical Inner Sydney slum of C. J. Dennis’s Sentimental Bloke genre on the West/Woolloomooloo side of Victoria Street and a collective of high class apartments on the East/Elizabeth Bay side of Macleay Street.37

Although the Cross could no longer claim uniqueness in its ethnic make-up, it could capitalise on the well established coffee shops and delicatessens that could offer a more diverse range of fare than the average suburban shopping centre. The idea of suburban emporia was barely a decade old38 and Roselands was only starting to offer Wiley Park residents the World in air-conditioned comfort.

Still the Cross continued to define Sydney to the outsider. From Nino Cullotta’s desire to go to “King’s Bloody Cross” in They’re a Weird Mob39 to paintings like Swiss-born Sali Herman’s Park at the Cross, the migrant’s arrival in Sydney was, by legend, destined to include the Cross as some sort of initiation rite.40

In the 1950 photo-essay Portrait of Sydney41 Slessor had written that…

King’s Cross, indeed, is not Sydney. It is Sydney seen through the eyes of lonely and homesick aliens, the colonies of displaced Poles and Jews and Hungarians and the itinerant clusters of Americans.

Even the dispersion of migrant culture in Australia did not mean that the Cross was anything close to a typical suburban area. King’s Cross was ‘foreign’ even if it’s demographic make-up wasn’t… really.

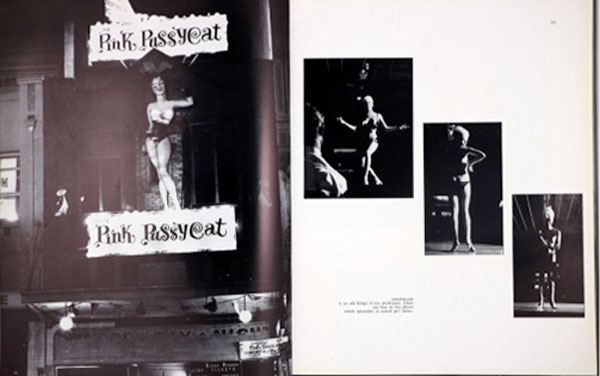

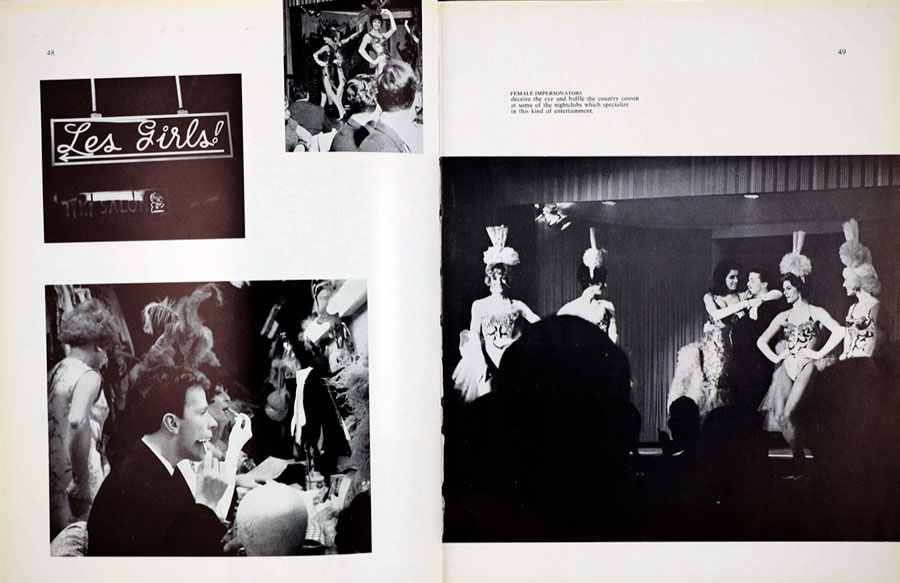

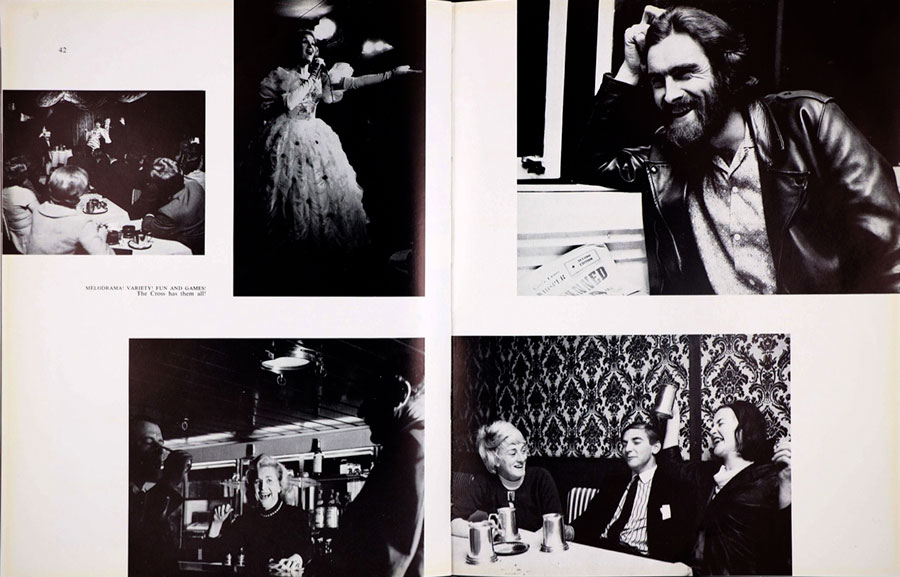

Walker’s photographs are distributed according to subjects, some are in sequences, others are linked by a common caption.42 As the title suggests, Life at The Cross is about more than just the Cross itself, it is about the residents and visitors in the streets and spaces. People are central to the book. It is not the buildings but the people and institutions who are legendary. Institutions like the Silver Spade, Pink Pussycat, Les Girls, Fitzroy Gardens, Wayside Chapels et al. figure in the mid-sixties legend and are thus seen in the book.

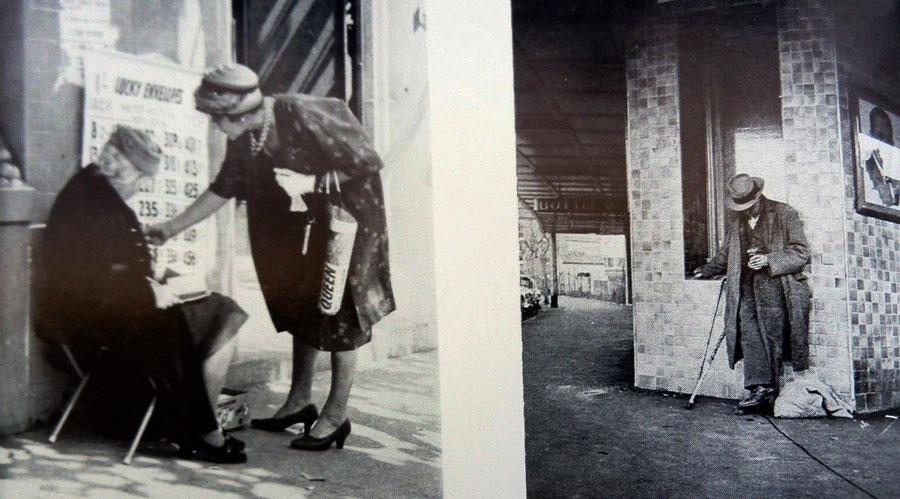

Life at The Cross is very celebratory in its approach to life. Strippers and Bag Ladies, Bodgies and Mods, inquisitive boys and prim schoolgirls, loving couples and sailors’ companions are shown, coexisting in a world divided between intellectual Bohemia and bawdy nightlife. The sixties cast an omnipresent influence over the book. Icons and events such as Beatlemania, Mini Minors, The Chevron, Sex and the Single Girl and coffee lounges galore appear.

Interestingly, the only colour found in the book is the blurred night time exposure of William Street on the dust jacket. Following the Family of Man style of human interest photography, the main illustrations are in high contrast monochrome. Physical colour is not necessary to reinforce the colourful lifestyle of the mythical Cross.

Although confined to a small area of Sydney, Walker maintains King’s Cross’s context in the City of Sydney by showing several panoramic shots looking towards the Central Business District and from the waters of Elizabeth Bay. Conrad Martens’s painting of Elizabeth Bay House is reproduced alongside a photograph taken from the same viewpoint, contrasting both the architecture and social status of two eras.

The background of vice that dogs the area’s reputation is covered by a spirit of positivism, Walker’s photographs avoid all but the remotest reference to prostitution (The sailors’ companions could be prostitutes but no specific accusation is cast). The greatest vice to be found in Life at The Cross is excessive alcohol, even so, it is in the course of merry-making rather than dereliction.

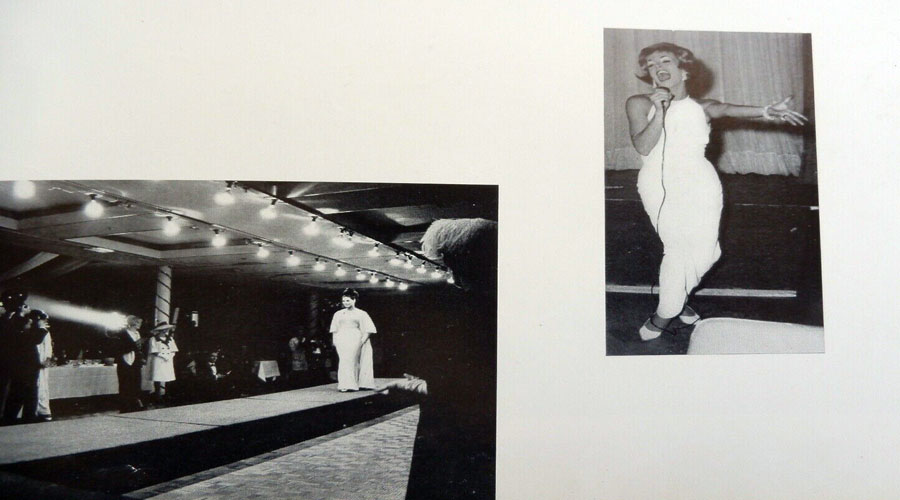

A mural of naked men and effeminate sailors in the background of a bar room in one photograph is the only hint of a pick-up joint, homosexual or otherwise. Slessor’s illustrated account of the exaggerated youth of typical striptease artistes is far wittier than any modern expose on the exploitation of young runaways could attempt to be. Perhaps no one wanted to believe that the girls would really be that young.

On a higher cultural level is the world of bookshops, the Clunes Gallery and the myriad of established painters, writers and composers with their young followers. A painting by John Olsen hangs above a discussion group, the next time Olsen’s work was seen in a Ziegler book was his tribute to Slessor’s Five Bells at the Opera House. The very presence of Slessor as the narrator reminds the reader of the literary importance of the Cross. A cabaret singer competes with ‘We Love The Beatles and 2UE’ badges on screaming teenyboppers as the musical mainstream of the Cross.

The publication of Life at The Cross capitalised on a part of Sydney as a promotion for the city in its entirety. Once the sleaze had taken over the reputation of King’s Cross, the publicity machine turned to the Rocks as Sydney’s interesting backwater and Paddington as the Bohemian quarter. The former was an example of the changing fortunes of tourist sites; during the sixties the city council would have been glad to oversee the demolition of all but the oldest of the area’s buildings but the Green Bans left the city needing a new use for the Rocks.

Life at The Cross was intended to appeal to a primarily tourist market. Possession of the book was similar to the Tomcat cards given to visitors to the Pink Pussycat, it indicated the owner’s supposed involvement with the Cross. It also makes a good photo-Essay and literary summary of Sydney’s renowned Bohemia.

|

|

| #23: King’s Cross by Day. Life at The Cross, 1965. |

| |

|

|

| #24: King’s Cross by night. Life at The Cross, 1965. |

| |

|

| #25: The Arts of The Cross. Life at The Cross, 1965. |

Sydney Builds an Opera House was published in 1973. It was the first volume in a planned trilogy. Only the second volume, however, appeared, Sydney Builds an Opera House, in 1974. The third volume was to have been a history of the performing arts in Australia titled The Performers. Ziegler included an in depth study of the performing arts in Australia 1901-1976, which probably incorporated the basis of The Performers.

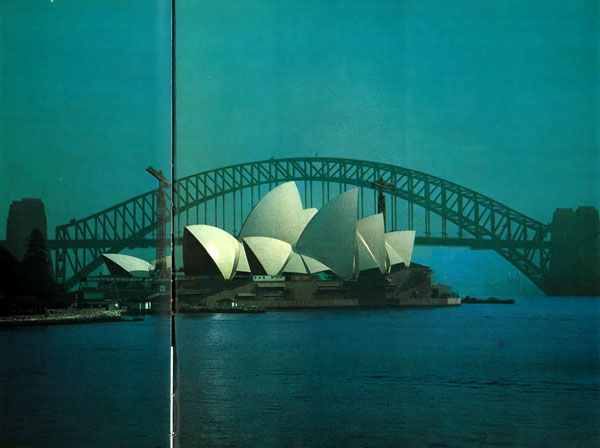

Sydney Builds an Opera House is chiefly a photo-essay following the construction, from the demolition of the Fort Macquarie Tram Depot to the eve of the opening ceremonies, the latter being the subject of Sydney Has an Opera House. The story of Bennelong Point up to the start of construction is illustrated by Arthur Boothroyd and there is a textual history of the project featuring other illustrations.

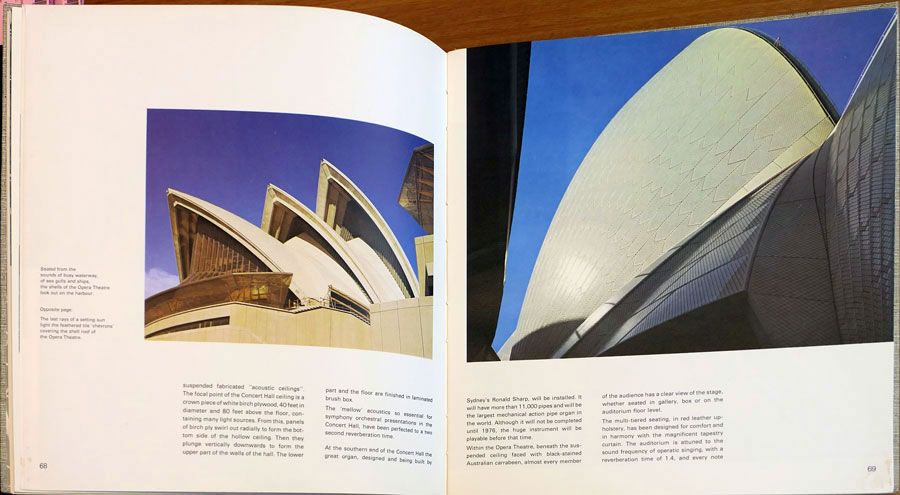

The main photographic content is by Max Dupain. The existence of these photographs is fortuitous, as Dupain explains that his studies of the Opera House were ‘not a commission but a labour of love.’ 43 The order of the photographs is chronological, with the layout by Alan D. Ziegler.

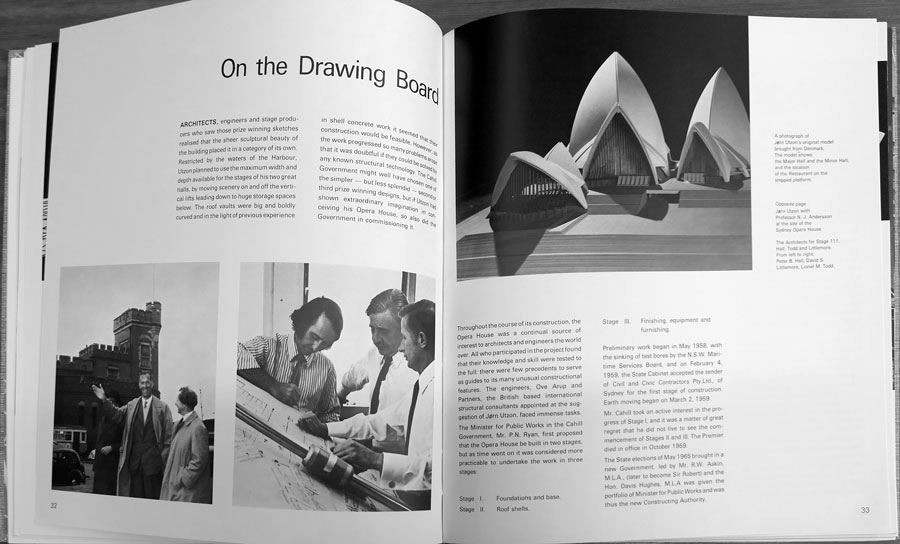

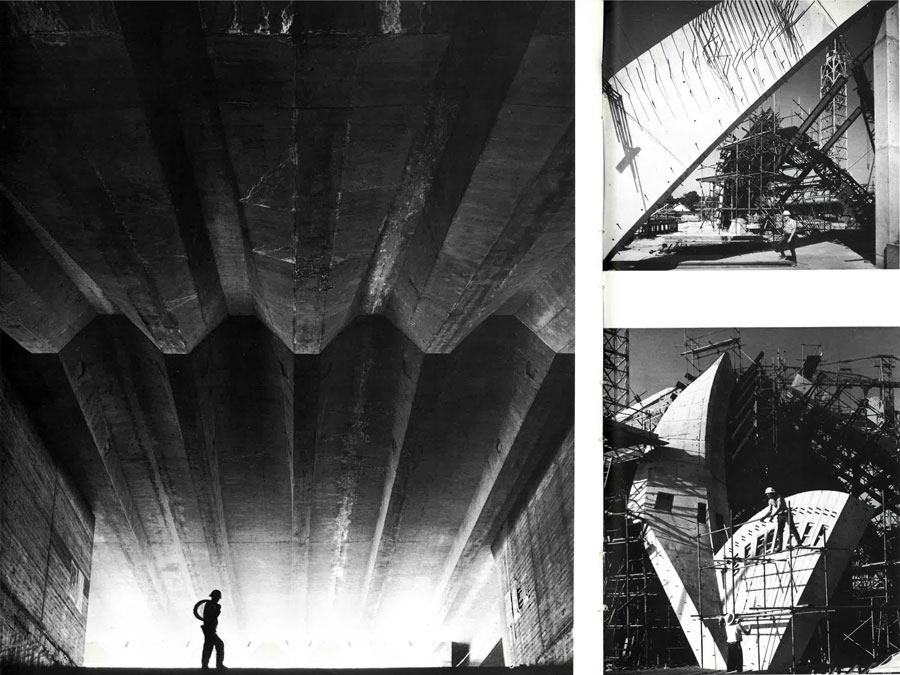

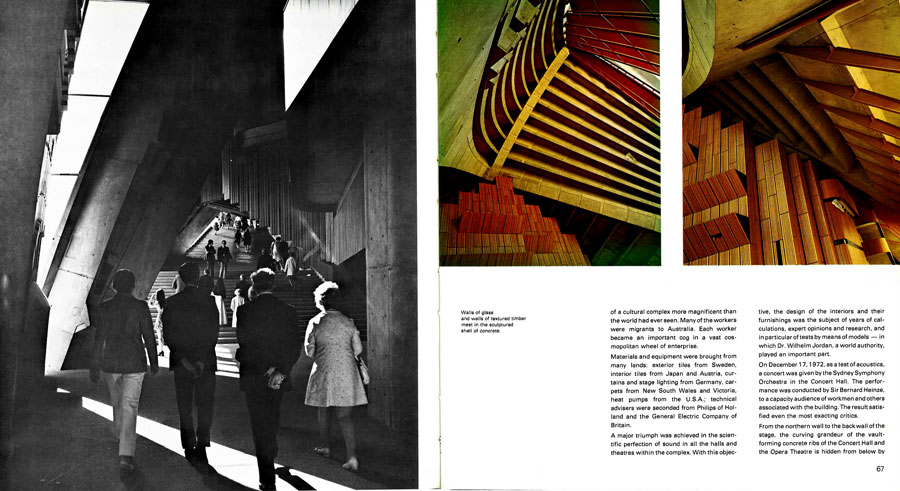

Architectural photography has been the main breadwinner for Dupain, his work earned him an Honorary Fellowship of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects.44 The curved white structure of the Opera House, present in its shape even in the early days of construction, is an ideal model for Dupain’s ‘aesthetic of the light picture with reference only to natural phenomena’ 45 , with its purity of form. Another of Dupain’s skills is his ability to blend human interest into his architectural photography. A silhouetted workman carries a coil beneath the majestic staircase supports. Elsewhere a workman in dirty white overalls inspects a clean white tile segment.

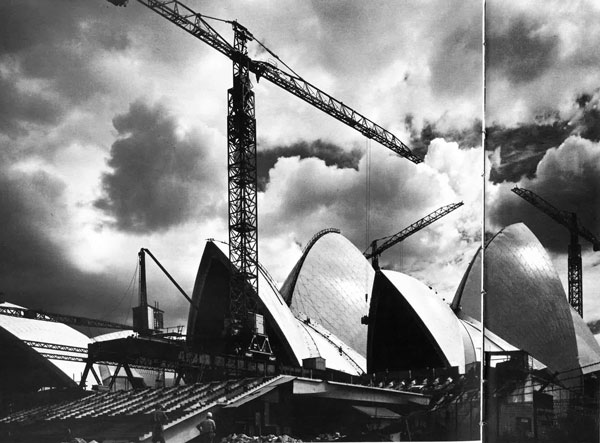

Dupain’s photographs of the construction concentrate on the structure. Within the text, however, there are references to the long and controversial troubles with the project. Plagued by engineering and design difficulties and constantly changing estimated completion dates which resulted in the resignation of architect Jørn Utzon in 1966, the building’s construction took much longer than anticipated. It had begun in 1958 but the centre was not open to the public until late 1973. The funding came primarily from a public lottery which, although financially successful, was marred by the kidnap, ransom and murder of Graeme Thorne, the son of a lottery winner, in 1960.

Although the text at the start of the book acknowledges these setbacks, the purpose of the book is to celebrate the architecture. The grandeur of the structure is evident at the start of the book, from the size of the site after the demolition of the Tram Depot to the murals and tapestries by John Olsen and John Coburn. The presence of workmen in many photographs establishes the scale of the buildings. The surrounding waters and low-level paths present opportunities for views of the construction which indicate the future appearance of the building to approaching visitors.

The cover photograph of the Opera House at night under a full moon isolates the white shells from the distracting surroundings. Only a dim scaffolding by the restaurant shells belies the completeness of the image, other signs of construction have been retouched.46 Several other night shots appear in the book. On his Opera House photographs, Dupain has said that ‘Architecture and the night photography are complementary because I believe the mystery of architecture can well be intensified at night.’47

The Opera House was a triumph for Sydney beyond the provision of a performing arts centre. Its prominent site and unique shape counteract any inefficiency as a theatre centre. Melbourne’s Art Centre, designed by Sir Roy Grounds, has similar functional difficulties although its diverse range of facilities and convenient site overcome them. 48 The Opera House is an easy symbol for Sydney to be sold on postcards and tea towels as well as an attractive finial for both Circular Quay and Macquarie Street. The book exploits this potential as well recording the history of this important addition to Sydney’s architecture.

Sydney Builds an Opera House and its sequel Sydney Has an Opera House both capitalised on the public attention given to the centre. The Performers was not as lucky but perhaps the topic was too limited for a public more interested in the building and opening pageants than in concerts and plays.

Although Dupain submitted work to Ziegler after Sydney Builds an Opera House, this book marks the end of Dupain’s thirty-three year contribution as a principal photographer for Oswald Ziegler Publications. It is also Ziegler’s final photo-essay style publication, the later volumes were more reliant on illustrated texts than visual continuity.

|

|

|

| The human scale within the Opera House. Sydney Builds an Opera House, 1973. |

| |

|

|

| #27: Clean white tiles and dirty white overalls. Sydney Builds an Opera House, 1973. (image to be replaced) |

| |

|

| #28: The shells near completion. Sydney Builds an Opera House, 1973. (image to be replaced) |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Notes:

I. Life at The Cross

- Ziegler’s Australia 1901-1976 points out that The Sentimental Bloke was set in Melbourne’s Central Market, p 112.

- Peter Spearitt, Sydney Since the Twenties, Sydney, 1978, pp 226-227.

- Sydney, 1957.

- 1947, collection Art Gallery of New South Wales.

- op cit n. 18.

- Some of Walker’s photographs of The Cross had appeared in Australia From the Dawn of Time to the Present Day in 1964 and others appeared in Australia 200. 1770-1970.

II. Sydeny Builds An Oprea House

- Max Dupain, Max Dupain’s Australia, Melbourne, 1986, pp 204-205.

- ibid. Inside dust jacket.

- ‘Factual Photography,’ essay in Ziegler’s Australian Photography 1947, pp 10-12.

- op cit n. 44, Melbourne 1986. The same photograph as used on the cover of Sydney Builds an Opera House is reproduced on page 204 of Dupain’s anthology in which the unfinished granite walls and support cranes are visible.

- ibid, p 195.

- Judy Annear, ‘A Story of Modern Art, Outlining Some Problems for Australian Museums,’ Art & Text, Number 17, April 1985, pp 63-72.