|

|

Home-Page / Intro & Acknowledgements / Chapter 1 / Chapter 2 / Chapter 3 / conclusion / illustrations / references

Landscape of Virtue:The Life and Work of Photographer Wesley Stacey – Ziv Cohen 2003 Chapter three:Stacey Leaving Sydney

Following the completion of Timeless Garden, Stacey and Williams departed Sydney in favour of Thubool, the 240acre sea-side property Stacey purchased with Bill Ferguson and Phillip and Louise Cox under the legal title 'Tenants in Common'.

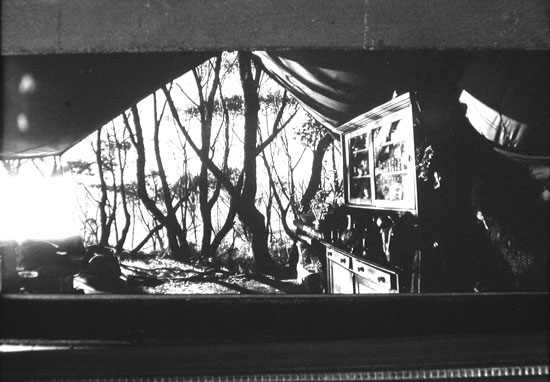

While spending more and more time down the south coast, Stacey continued to photograph and exhibit his work. His growing reputation as an Australian photographer had him frequently appearing in selected publications, art critiques, group exhibitions and major collections. By the end of 1970, at the age of thirty-eight, Stacy had already co-authored six substantial publications of architectural and landscape photography; additionally, he published two books concerning contemporary Australian society and one book featuring an extensive survey of Australian nature. He had also produced six solo exhibitions and participated in six major group exhibitions. Stacey maintained his contacts with the photographic industry and people, some who became increasingly influential in the field. Gael Newton, whom he met whilst an activist in the Australian Centre for Photography and remained close friends with, later became a person of authority in the field. Her reflections on the work of Stacey in the 1970's indicates Stacey continued to evolve and develop; and by doing so, he proved to benefit Australian art and culture even when removed from the cultural hubs of Sydney and Melbourne 'His recent interest in critical discourse on the nature of landscape art... has added an intellectual dimension to his concept of the landscape, particularly an awareness of the interpretive role of landscape photography. * (Newton, 1991, p. 2) Despite Stacey's continuous roaming of the country in his campervan, by 1978 the South Coast had increasingly permeated his life and work. The book Baronda, published together with local poet and writer Max Williams, testifies to Stacey's growing ties with the region and the local community. 'Baronda was the first creative thing I did after leaving Sydney1 (Stacey, 2003 c). It is a small format publication containing twenty-three poems by Williams and twenty-six black and white photos of forests, farmland and coastal estuaries by Stacey. Baronda's poems and imagery echoes the South Coast's characteristic atmosphere of misty waterways, hilly wooded terrain in the shadow of the Great Divide, and the somewhat isolated rural lifestyle (Stacey and Williams, 1977).

Environmentalist, forestry and wildernessThe mutual relationship between photography and the environmental movement, the perception of wilderness in contemporary society and the relevancy of Stacey's personal and professional contribution to these social issues will be discussed here , The south coast of New South Wales, where some of the last remaining expanses of tall forest in Australia stands, is an area markedly different in nature, culture and temperament then the central and northern parts of the continent's east coast. While most of the east coast is dominated by the metropolitan axes of Sydney, Brisbane, and to a lesser extent Cairns, the coastal land that stretched to the south of Sydney had been lapsed by a major transport route, industrial development and population growth. Colder weather, higher rainfall and rough seas stunted potential tourism trade whereby accentuating its cultural isolation. The region of southern New South Wales and northern Victoria, similarly to Tasmania's wilderness areas, have been the battleground of wilderness conservation epitomising the environmental movement that became a major political and cultural issue during the 1980's and 1990's. Stacey never described himself as a 'greenie'. He maintains a pragmatic attitude towards the popular environmental movement and, although his photography did take part in the early conservation movement campaigns since the mid 1970's, Stacey's individual integrity stops short of belonging to a political category. However, considering Stacey's growing affinity with wilderness and nature, together with the exposure to many forms of environmental degradation during his extensive travels, it is reasonable to assume that the sensitive artist had experienced a shift from the sphere of social cultural critic towards professional and personal empathy with the natural environment and its welfare. Living on the land, surrounded by forests of Spotted Gum (Eucalyptus maculata), Stacey soon became involved with the issues gripping the region: forestry management, logging of remnant vegetation and the implication these issues have on both the community and the landscape of the area. The emergence of the popular environmental movement during the 1980s in Australia was preceded by a long history of concerns and efforts by public institutions and individuals to manage the nation's non-renewable natural resources in order to preserve their economic viability. Growing popular concerns regarding protection of nature and wilderness for their own value later joined resource management, which can be seen as stemming from their perceived psychological and social values such as aesthetics, recreation and refuge from an ever-industrial and crowded world. By the end of the twentieth century the two issues above have largely been merged into one following broad understandings that the integrity and future of natural resources demand their conservation whether for cultural or economic purposes. The emerging fact that cultural and aesthetic values are having an important economical and monetary value as a consequence of population growth and changing lifestyle trends is now common knowledge. Similarly to the heritage conservation movement, nature conservation and photography practices are closely linked as both science and social perception were aided by imagery to deliver their message to their audience be it institutional decision making, lobbying interested parties or the broad community where grass roots activity fostered. The late twentieth century nature of the environmental movement as a global phenomenon was an evolution of a process that began in isolated, regional incidents that later grew into national dimensions. This coincided with the growing scientific and popular understanding of the environment as a collection of ecological systems in which the wellbeing of its entirety depended on the health and performance of each smaller ecological component. Forest management and, in particular, the logging of old growth forests for the wood-chipping industry will serve here as an example of the broader issues of the environmental movement and as an demonstration of Stacey's professional involvement in the assessment of forestry management of the south coast forests in the mid 1970s. Attempts to manage forestry practices in Australia to ensure the longevity of this important resource, as well as the associated resources such as soil and waterways, have been documented from the early days of the colony; however, they were rarely enforced. Indeed, for the first one hundred years of the colony the value of the timbers as a building material together with the value of the land for agriculture production saw the forest itself regarded with hostility and contempt '...the general public encourage the minister... so he loudly joins in the cry of 'manless land for landless men'. To the minister all land is potentially agricultural, all is too valuable to devout to forestry' (Powel, 1988, p.160; cites in Young, 1996, p 74). By the 1930s, forestry sciences were fast developing and following the European concept of Sustainable Yield, the 1935 forestry amendment act was set to secure the future use of forests and timber. More importantly, the protection of associated catchments, recreation, grazing and wildlife conservation was established. Foresters were seeing themselves as the protectors of forests against expanding agriculture; however, the national and world wide growth in population and industrialisation placed such a heavy demand on the production of timber and wood products that a massive increase in logging and the introduction of new practices such as softwood plantations began including, most notably, the clearfelling of native forestry to supply woodchips to Japan's paper industry beginning in 1967. The new forestry practices that replaced selective loggings in Manjimup in Western Australia and near Eden in the far south coast of New South Wales had left a trail of severe visual impacts that drew loud public outcry; and by 1974, the fight for the forest was on. The controversy over the management of national forests had yielded many commissions of inquiry into the matter resulting in a succession of legal and practical consequences and the allocations of large tracks of lands to national parks and other land titles according to their ecological, political and economical standings (Young, 1996, p. 73-104).

Of relevance to this thesis is the New South Wales Government's South Coast Forest Advisory Committee set up in 1978 to examine the practice of clearfelling of old growth forests in the Eden area. Stacey became the photographer for the advisory committee and during that year he travelled and photographed what is now considered the last remaining old growth forests in Australia. Serving as a photographer for an inquiry body, placed upon the photographer and the photographs he produced was a responsibility to be as impartial and true to the sights and sites under examination, where Stacey's inclination towards a pragmatic and objective vision have been accentuated and his existential and philosophical tendencies must be tempered and left out of the picture. His distinct style and clarity of vision however remained apparent, and the images brought to us by him are firsthand testimonies of the indiscriminate destructive clearfelling logging that has come to represent in Australia's environmental history (National Gallery of Victoria, 1986, p. 2).

Meeting Guboo Ted Thomas- Stacey and the Aboriginal movementWandering in the Australian forest and living amongst the small community of the South Coast, Stacey was destined to encounter the presence of the local aboriginal community and traces of their long occupation of the land. While recognizing shell middens on the bay where he lived, and aware of places of indigenous culture in the heart of the forests he photographs, Stacey's actual initiation to the world of Kooris, the Aboriginals of the southern east coast, happened when he met Guboo Ted Thomas. An elder of the Wallaga Lake Aboriginal community and a vocal political activist residing only several kilometres from his home, Guboo Ted Thomas left a lasting impression on all who met him, and Stacey was soon also captivated by the man and the cause he represented. Since photographing the forests and their logging, Stacey's work flowed on to feature the cultural landscape of the traditional inhabitants of the Australian forests. Documenting sacred Aboriginal sites led Stacy to a greater awareness of the Aboriginal plight for self-determination, land rights and equal opportunities, resulting in the book After the Tent Embassy (Stacey, 2003:a). As a prefix for these photographic endeavours, outlined below is a brief summary of ethnicity theory, followed by an overview of relevant cultural elements of Australian Aboriginals and its relation to landscape photography.

Ethnicity- historic world viewIn the aftermath of the two World Wars, a rapidly changing world had prompted the question: What is ethnicity? While some social and political scientists viewed ethnicity as linked to primordial forces such as kinship, language and religion, others saw racial and cultural identities as having socio/political foundations stemming from early power- plays in the formations of states and other hegemonies. Such conditions, it argued, are the driving force behind the existence or lack of racial separatism which itself is the reaction to the degree of accommodation and fulfilment of the needs of the periphery by the centre of power. Here, the rise in ethnic consciousness in certain communities is suggested as being a response to feelings of disadvantage in relation to income, housing and social status. During the 1950s and 60s, the prevalent political theories towards ethnic paradigms were common, corresponding with the modernist movement's rejection of the past, and the prediction of population assimilation and diminishment of ethnic diversity in the face of a new world order 'Marxist interpretations insisted that ethnicity was merely a 'false consciousness' which could surely disappear as the historical dialectic worked itself out' (Paydon, 1994, p. 173). Despite such predictions, ethnic awareness and related political activism has responded to the onset of modernity by an uprise of minority and peripheral groups in all parts of the world seeking political and economic goals and security. Western Europe was the first to experience ethnicity becoming a dominant political and sociological process, but soon the rest of the western world was to follow. Minority groups of migrants, import labour and indigenous populations began to challenge the hegemonies of power in the USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, leading to major changes in the legal, cultural, territorial and political map. In Australia, the waves of migrants from south Eastern Europe and later from Asia had led to the abandonment of the official exclusive Anglo-Celtic identity and the development of multi-culturalism, a model later used in England's ethnic policies to accommodate its own cultural diversity. While New Zealand's Maori population had managed to greatly affect the nature of the state, Australia witnessed only little changes in Aboriginal rights (Paydon, 1994, p. 170-174). The Aboriginal voice however was not silenced and several landmark processes, events and decisions took place during the 1970s and 80s, some of which will prove to be relevant to this thesis as discussed in the following sub chapter. Photographic representations of Black Australia'A people or a class which is cut off from its own past is far less to choose and to act as people or class than one that has been able to situate itself in history. This is why - and this is the only reason why — the entire art history of the past has now become a political issue' (Berger, 1964, p 33).

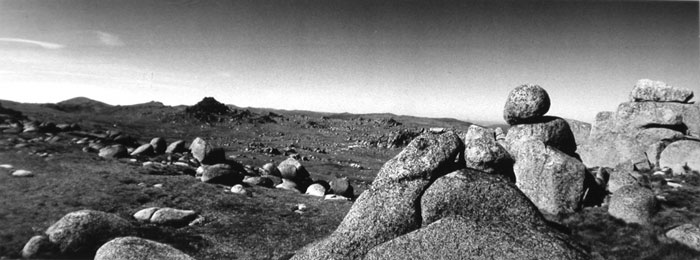

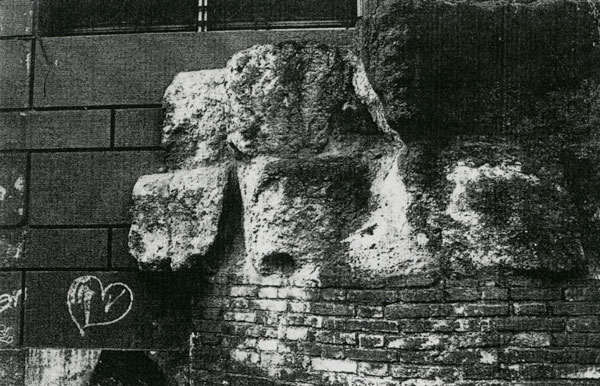

Dealing with the contentious and often painful history and reality of Aboriginal Australia seems to only be in the capacity of the few. It is only in the late twentieth century that Aboriginal culture upon its inherent qualities and the ordeal it has undergone since European colonisation, has penetrated the broad Australian social consciousness and became represented in art, media and political affairs. Starting from the late 1970's, an increasingly high profile in the judicial system and history books emerged, paralleled by a flood of images representing Aboriginally in press media, cinematography, painting and sculptures, commercial arts and photography. Film and still-photography were particularly instrumental in the rise of the Australian Aboriginal movement through the late 1960's and 70' by bringing images from their living conditions and cultural identity to the common household. Through all the different means of photographic methodologies such as historic documentation, scientific data, narration, photojournalism, portraiture and fine art, photographers, as well as public institutions and aboriginal communities, were fast becoming informed participants in the Aborigines' plight for self-determination, land rights and reconciliation, issues haunting Australia's past and future. For the early individual artist and photographer of European origin, working with the issues and people of the indigenous community was a process inherently more challenging and demanding than working in his/her native culture and habitat. Photographing Australian Aboriginals, related sites and artefacts, usually required a strenuous physical and mental journey to places far away from the known and safe, usually by invitation only. In many such occasions the resulting images that were brought to the public eye depicted the often-harsh reality, deprived and painful. It was also necessary to possess a certain maturity and experience that often only comes at the later stage of the artist's life and career; evident in the career path of other Australian artists is a tendency to explore their world in increasingly widening circles from their home towards national, global and universal subject matter, and their encounters and occupation with Australian natives is closely linked to their discovery of Australia's deep interior landscape and the forces acting upon it. However short might be the period of preoccupation with Aboriginal themes and issues, the impact of that culture previously hidden from their eyes and consciousness has left strong marks on the work and life of these artists and through it on the Australian culture at large. Painter Russell Drysdale, whose work had influenced Stacey in his youth, had similarly discovered the faces and landscape of the Australian indigenous community whilst travelling to remote regions of the continent in his mid career (age 41). Only published after his death, the 1950s photographs of 'This most Australian of artists' (Boddington, 1987, p. 9) captures his first encounters with the Australian Aborigines and his growing understanding of the landscape and the life in outback Australia just before it was modified by massive migration intake, expansion of industry and economy and Aboriginal politicisation. Drysdale's awareness of the landscape and image of Australian Aboriginals did not carry a strong political or social message; however, their influences marked his later work, articulating a new and emerging popular view of Australia (Boddington, 1987, pp. 33-36). Stacey's participation and photographic contributions to the field of indigenous Australia can be divided into two broad categories for this discussion: first will be his work in documenting sacred Aboriginal sites; second will be his contribution to the political campaign for land rights epitomised in the book After the Tent Embassy which he published together with his partner at the time, Narelle Perroux. The meanings and representation of Aboriginals Sacred SitesCosmology serves to orientate a community to its world, in the sense that it defines, for the community in question, the place of human kind in the cosmic scheme of things. Such cosmic orientation tells the members of the community, in the broadest possible terms, who they are and where they stand in relation to the rest of creation (Mathews, 1994, p. 12; cited in Bowie, 2000, p. 119) The cosmology of different communities, coming into effect through different forms of expressions, evolved according to the dictates of time and place. Environmental cosmology and totemism will be of specific relevance here, as environmental cosmologies reflect consciousness of the environment as the sustaining foundation of human life, an interdependency that is embodied in rituals, beliefs, lifestyles and land management. Totemism reflects such attitudes towards nature where natural features such as animals, plants and landforms are seen as an outwards manifestation of God and creation, used to represent and define the community's internal and universal relationships of rituals and myth. Arguably some of the most explicit environmental cosmologies in the world are to be found among the Aboriginal people of Australia... For all Aboriginal groups in Australia the land is at the centre of a mythical order that regulates the relations of people with one another and with the physical environment' (Bowie, 2000, p. 142). In Australian Aboriginal mythology, totemic sites are seen as evidence of ancestral beings that passed through the landscape during the 'dreamtime' period of creation, whereby they modified the land and created special 'sacred' sites. Rituals and mythology are retold and enacted by initiated elders to reaffirm the past, enforce group identity and cohesion and express a spiritual totality where humans and nature are closely linked. The cultural overlapping between the sacred and the profane also bears physical significance when land usage, genetic ties, food production and territories are concerned, a distinction powerfully demonstrated in the accounts of the habitation history of Australian Aboriginals before 1788. The two hundred years of colonisation left little room for Aboriginal communities to negotiate their claims of ownership, partly due to the degenerative process their communities were to overcome, and partly due to the erasing of what little physical evidence their long lasting habitation had left on most of the continent. However, by the 1970' s it became quite clear for most of legal, political and popular Australia that Australia's indigenous community had, and still has, an undeniable spiritual and existential bond with the Australian landscape. This awareness was the result of a long struggle by Aboriginal individuals, isolated communities and their peers, a struggle that first had to define for themselves their position and later convey this position to the white Australian public and system. While sacred sites tend to be geomorphologic features small in scale and outstanding from the surrounding landscape such as mountains tops and rocky outcrops, the profane landscape has a utilitarian nature and encompasses large tracks of land where day-to-day habitation and sustenance can take place. When the European colonisation of Australia took place, the coastal plains and, later, all arable and broad forested lands were soon taken from the Aboriginal people to be exploited for their natural resources; the least accessible sites of no economic value generally remained undisturbed. While physical manifestations of Aboriginal occupation in the landscape does not necessarily define a place as sacred, a site that is deemed as sacred undoubtedly demonstrates traditional historic Aboriginal presence and habitation, therefore presenting a case to claim ownership. Sacred sites have become a synonymous attribute to the Aboriginal campaign for land rights and self-determination; the declaration of a site as sacred has become closely linked to a political and legal claim of ownership over land. In the absence of much physical evidence of use, or habitation and occupation in Western society terms, sacred sites are used as a tool for ownership claims in addition to demonstrating a system of values, social structures and legal titles that are different from the European system/s yet just as valid (Lippmann, 1994, pp. 33-48, 168-172). Photography was an important tool in the undertaking of this twofold epic. The involvement of Stacey in Aboriginal culture cannot be seen as circumstantial alone; an analogy can be made between the world views and values of this culture and the resonance they may have had within the photographer's own ideology and interpretation of the cosmological world and consequently human relationships to the landscape itself. It is argued here that Stacey's participation in the Aboriginal cause has enforced and further expressed his already pre-existing tendencies to view humanity, the environment and their spiritual relationships in different light to his native Western cultural worldview, actions and interpretive mechanisms. The opposing models of Western culture and Australian Aboriginal culture are defined by their respective understandings of the world and how these relationships determine their lifestyle, social interactions and environmental operations. In the aim to evaluate the values and functions of a certain society, the notion of adaptive or maladaptive cosmologies has been developed by anthropologists, framing it in terms of the levels of disparity between a social image of the physical and natural world and the actual Rappaport then continues to compare the levels of environmental performances and its impact upon ecosystems between small scale communities with mythical 'irrational' cosmologies to Western societies of global order in which economic values guide its environmental conduct. In his view, societies that people the world with spirits might sustain more adaptive environmental practices as they maintain a hierarchy of higher order systems of ultimate goals and systems of lower order instrumental values, whereby protecting essential social arrangements from erosion caused by changing lower order values. In contrast, Western economic models that see the world in mechanistic terms can result in lower order values (accumulation of wealth, physical pleasure) to usurp values of greater generality and can often assume the sanctity traditionally belonging to abstract concepts such as social cohesion or liberty '...all with equally disastrous results for the ecosystem' (Bowie, 2000, pp. 118-123). The Australian Aboriginal community at large has instigated an alternative view to the so far prevailing Western-orientated society in power, a view that sees the relationship between humans and the environment inclusive of its interpretation of religious concepts such as creation and metaphysical forces that might enact upon the world. Apart from cultural values that govern inter-social conducts, Australian Aborigines' conception of the land, its resources and appearance has revealed itself to possess land management knowledge that is more sustainable in ecological terms by reducing landscape disturbance and degradation. In participating with the advocacy of such interpretations of the land and an alternative approach to harvesting natural resources, Stacey's photography promoted a broadening of Australia's common cultural and environmental values. This process was made possible through his own personal experiences, passing from the traditional Western practices of economic rationalisation through to his encounters with undisturbed nature, culminating for now in his findings of indigenous cosmologies and their commonly perceived balanced approach to their environment.

Preserving his family tradition, Guboo Ted Thomas was actively involved in local and national Aboriginal affairs and ceaselessly travelled the continent lobbying for cultural revival and political recognition of his people (Morgan, 1994, pp. 70-74).

Wallaga LakeLocated between Narooma and Bermagui, the Wallaga Lake Aboriginal reserve was established in 1891 on land long inhabited by the Yuin tribe whose totem is the black duck. Perhaps more than other culturally significant places in the region, the Yuin considers the mountains of Gulaga and Mumbulla as sacred sites having high religious and educational value. The mountains, used for traditional cultural and spiritual purposes from time immemorial, also exude a great visual presence among the regional landscape as they dominate the skyline from hundreds of kilometres away. The status of Mumbulla Mountain as a significant and sacred site is evident both in the traditional oral mythology of the Yuin and in the present life of the community, manifested through cultural proceedings, social interaction and the local economy. The mountains provide opportunity for educational and recreational activities and, additionally, support for commercial tourism activities and the local production of literature and artefacts.

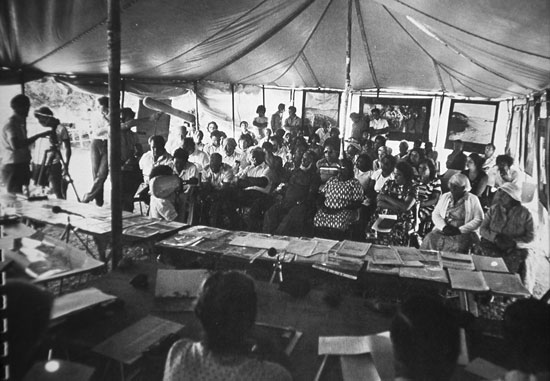

'The Law Comes From the Mountain'Mumbulla Mountain can be seen as embodying the Australian Aboriginal campaign for land rights and self-determination. During the 1970's it was the ground upon which the local Aboriginal community fought for these issues, a two-fold process whereby the site's mythological and political presence was instrumental in the formulation of their own socio-political identity and their political strategies. The combination of written stories from the oral tradition of the Yuin, together with Stacey's photographs, were extensively used for educational as well as political propaganda purposes in the form of books, newspaper media and a travelling exhibition that toured Australia between 1975 and 1978.

This was a format that was later used extensively in the on-going campaign for the protection of culturally and spiritually significant sites of Aboriginal Australia. Sacred sites since increasingly became recognised as important cultural and economic resources to be cashed-in by mainstream Australia

On this day when this page is written, June 7 2003, The Sydney Morning Herald announced what might be a final chapter of the preservation campaign of Mumbulla Mountain and sister Gulaga Mountain with the hand-over of the area back to its traditional Aboriginal custodians (Woodford, 2003, p. 5). Stacey's involvement with the Australian indigenous movement continued throughout the years in varying degrees of intensity, and in 1981 Stacey received a grant from The Australia^ Council for the Arts to continue his photographic work.

Landscape PanoramaThe 1980's represented a golden era for Australian culture and the arts, responding to the maturing of social changes such as multiculturalism, reconciliation with the Aborigines and closer relations between Australia and the Asia-Pacific region. With Australia celebrating its bicentenary in 1988, it presented the world with a vivid vision of itself, flourishing with visual and performance arts that celebrated Australia's unique flora, fauna and landscape which had, until recently, been hidden from the eyes of the world in its antipodean existence. Fast-growing tourism, a high profile in the worldwide media and wide governmental support encouraged Australian art, and the art industry raised the demand for both commercial production and iconic nationalistic artefacts. Between 1980 and 1988, whilst Stacey himself roving around the Australian outback, his landscape photography participated in seventeen group exhibitions, four of them in countries overseas:

Art critics were viewing Stacey's photography favourably and ever since then it featured in an abundance of relevant literature pronouncing its cultural and artistic significance. Art Critic John Spurling critically reviewed the 1981 Eureka! Australian Artists exhibition in the London Serpentine Gallery as;

Stacey's photographic documentation of the wood-chipping industry and of the sacred sites of the South Coast also won acclaim at the exhibition of photographs from the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria that toured Australia in 1986 and in many other regional, national and international expositions since. Stacey's photographs were also starting to appear in publications of governmental departments such as the Forestry Department and the National Parks and Wildlife Services, indicating their value as scientific anthropological and archaeological documentation. While spending much of his time travelling and photographing the land, forming many new relationships with people all around Australia, old friendships continued to evolve. In the year 1980 his partner Eleanor Williams left Stacey in favour of an acquaintance of his, Aboriginal activist Kevin Gilbert (Stacey 2003 :c). In 1981 Stacey had met twenty-one year old art student Narelle Perroux from Canberra, who joined him at Thubool and became deeply involved in his life and photography; later becoming a proficient photographer in her own right. Together the pair began a seasonal pattern of travelling from the East Coast to the Australian inland escaping the colder winters of the south coast; yet not before completing another remarkable contribution to the Aboriginal political movement with the 1982 exhibition After the Tent Embassy and the book of the same title published in 1983 (Stacey, 2003:c).

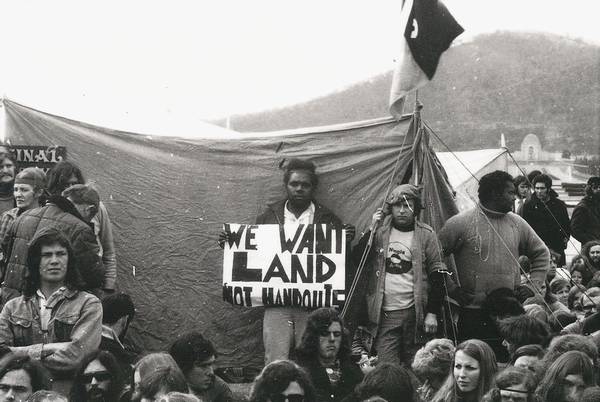

After The Tent EmbassyAlong the road for Aboriginal political self-definition and self-determination several milestones can be distinguished: the national referendum to change the status of Aboriginals in the Australian constitution taking place in 1967, the removal of the legal and ideological notion of terra nullius from the Australian constitution in 1992, the High Court decision of Mabo in 1992 and the establishment of the Native Title Act of 1993. The Mabo decision and the Native Title Act were culminations of a process beginning in 1963 when no rights for land ownership by indigenous people on the merit of their original occupation existed. In that year, a first legal claim of land ownership and the right to benefit from mining operations on that land was launched by the Arnhem Land people of Yolngu, relating to the Nabalco mining company's application to mine bauxite in the land they had inhabited since time immemorial. After eight years of deliberation, the Yolngu people had successfully demonstrated their own system of law recognized by the British legal system and the Australian government; however, its attributes were classified as religious and cultural whilst property rights and economic interests of the traditional owners were denied. The declaration by the then Australian Prime Minister Billy McMahon on January 25th 1972 that the Yolngu people will receive only trivial royalty rates from the mining of the bauxite became the launch pad of the first political rebellion of the Australian Aboriginal community against what they believed to be an official policy of deprivation and demise. In the early morning of the 26 of January 1972, Australia Day marking 184 years of colonisation, a group of Aboriginal activists had set up a 'tent' embassy on the front lawn of Parliament House in Canberra (Cope and Kalantzis, 2000, pp. 137-141).

The Exhibition After The Tent Embassy - Images of Aboriginal History In Black And White Photographs is a collection of images that were first shown at Paddington Town Hall in Sydney as part of the Apmira Festival in 1982. Part of the general movement to inform and voice Aboriginal issues, this venture was the result of a group of Aboriginal and European individuals, mostly from the eastern suburbs of Sydney. Stacey by that time had met many people connected to the Aboriginal movement through his work with Guboo Ted Thomas and their campaign down the south coast and he and Narelle were asked to participate in the exhibition. The exhibition and the book were a collaborative effort involving many individuals and institutions, from both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal background. The forwarding of the publication by an Aboriginal elder of an Arnhem Land tribe explains the motive and purpose of the venture from an Aboriginal perspective. To Wandjuk Marika, the main purpose of this photographic essay is to inform and strengthen the Australian Aboriginal community about their past, their connection to the land and their right for the land: their land. She also addresses the non-Aboriginal people of Australia;

The book The Tent Embassy contains photographs from the 1850s through to the period of publication, and its subject matter varies between contemporary Aboriginal life in different locations, historical anthropological documentation, sacred sites and rituals and modern- day protests such as the landmark event of the Tent Embassy. The photos are presented in chronological disorder which creates a sense of shock and dismay in the viewer's mind: an image of a dignified warrior is followed up by a no less dignified yet obviously dispossessed young protester in 1972; a portrait of an 1880's stolen child alongside someone suffering trachoma infected blindness in 1981. After the Tent Embassy was written and edited by writer, academic and activist of Aboriginal decent Marcia Langton. Stacey and Perroux did the photographic research as well as organising and constructing the exhibition. The book features 114 black and white photographs by twenty-nine photographers. Stacey is represented in the exhibition/book with five photos, three from the South Coast Aboriginals' places of significance campaign, one which documents the reburialceremony of Aboriginal remains in Wallaga Lake, and one which depicted the disturbing sight of a massacre site in Wentworth taken in 1981.

Topographical DelightsStacey and Perroux*s extensive photographic expeditions during the 1980's culminated in three bodies of work, each compiled in a large folio/album format. Western Waterways, From the Mountains to the Sea and From Bermagui to Broome are monumental photographic essays displaying Stacey's seasoned photographic skills, his attome eye to the diverse Australian landscape and his ability to form connections to the people he meets along the way, adding an important layer of stories and histories evident in the narrative nature of his work.

Later on, titled Topographical Delights by Stacey, these panoramic landscape images can be seen belonging to the traditional topographical art of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, serving the golden age of scientific explorations during that era. This art and documentation form that disappeared after the arrival of photography is distinguished from pure landscape art due to its concern for the precise documentation of landscape's natural and manmade features in which atmospheric and emotional conditions are only an implicit part of the picture. 'Stacey's work - in particular his focus on the enduring aspects of places - has more in common with the topographical artist' (Newton, 1988, p. 1). Stacey's Topographical Delights has much in common with the 1970's photographic style dubbed in the United States as 'new topographies', a style characterised by cartographic formalism widely used in the documentation of large-scale industrial and agricultural interventions in the landscape (Edward, 1999, p. 271).

While Stacey's documentation of the CSR gas pipeline construction in Queensland during 1985 strove for detached and objective documentation, the expansive panoramic vistas he brought back from the western waterways and his cross continental journey offered a perspective of the remote landscape of Australia richer in cultural and atmospheric information in which romantic sentiments can be detected. To exemplify by comparison, David Stephenson is an American born photographer who has been photographing the Australian landscape in a similar scope and style to Stacey's Topographical Delights. An analysis of Stephenson's work by Edward Colless in his essay Nowhere are befitted here to further illuminate some of the qualities of the genre in general, and of Stacey's Topographical Delights', Of course, photographs, like maps, fabricated the world they appear to record; and their edges reveal the limits of the language used to represent the world... Despite the intensely personal and reclusive, trance-like mood of Stephenson's gaze, much of the imagery cannot renounce the commission or propriety of an ecological doctrine which, like fundamentalist theological doctrines on art, insist that an inherent beauty guaranteed by providence need only be given explicit expression by art: that a faithful artist can see through the deceitful forms of the world into illuminations (Colless, Edward, 1999, p. 275).

The Western Waterways folio/album contains twenty large black and white panoramic photographs that are focused on showing the remote outback region of NSW and South Australia's major water catchments of the Darling River, extending to Sturt's Stoney Desert and Cooper Creek. 'Here are characteristic waterway environment — Billabongs and flood plains, sandy creeks beds, flooded forests and broad reaches, all leading downstream to lake Alexandrine. While defining the group of photographs in geographic terms and pre-empting the growing national awareness of the importance of holistic knowledge of water catchments in the arid continent, Stacey also leads the viewer on a trail laden with historic and national significance. Stacey brings here the environment of ancient Aboriginal grounds that were later encountered by a continuum of explorers, pastoralists, and tourists. 'This region of waterways looms large in history and in our Australian experience, it effects our national psyche' (Stacey, 1995 a).

From The Mountains To The Sea is a similar limited edition folio/album of twenty black and white panoramic vistas. This time the catchment in focus is larger and presented in a complete landscape sequence of hydrologic elements and their associated regions from the top of the catchment in the wooded western slopes of the Great Dividing Ranges to the mouth of the Murray River at the Great Southern Ocean in South Australia.

Earlier on in 1980, Stacey had purchased a new camera for these large photographic essays; an especially designed tool for landscape photographers carrying the appropriate name 'Tomiyama Artpanorama' with a 'Grandagon' lens. This heavy equipment demanded the use of a tripod and dictated a slower and more considered process of photographing with only a limited number of exposures allowed from one position (Stacey, 2003 c) The course of picture taking in which the technical and mental processes were elements of equal importance for Stacey, linking the resulting photo to the personal and psychological experience of the outer environment and to the ephemeral universal dimensions of human existence. Stacey's articulation of his mental journeys whilst photographing the landscape evinces an existential perspective that attempts to grasp all that is acting upon that moment. His writings of that period reveal a wealth of knowledge gained from a vigilant and inquisitive nature enriched by many readings and meetings with people along his path. Like his photography, Stacey's description of the process of photography and the nature of its relationships to objects and subjects aimed at distilling the essence from what might possibly be a conventional assumption. He probes deep into their essence by posing challenging questions;

Stacey does not present the reader or viewer of his photos with a formulated answer to such concepts; rather, he creates an opening for their understanding to evolve. Perhaps the experience and not the conclusion is the essence of being?

MarginalisationOperating away from the urban centres of Australia has enforced Stacey's position as a marginal artist, perhaps also echoing the tension that exists in Australia between its 'outback' and rural fringes and its heavily populated urban centres. The effects of such a position can be manifested through his level of exposure in addition to the shaping of the content and relevancy of his work; both can be measured in economic terms as well as ephemeral terms, such as artistic recognition and institutional support. An example of such a culturally and institutionally marginalised position can be deducted from an analysis of the catalogue of the Australian National Gallery's Australian Photographs exhibition (Ennis and Crombie, 1988). Ridge, Stacey's contribution featured in the catalogue is significant as it is the only representation of the Australian landscape that is intrinsically un-anthroposophic in nature, in which neither humans arid man-made forms appear. Of greater relevancy to this argument is the size of the photo in question, for Ridge is the second smallest picture in the catalogue, surpassed in smallness only by a photo of an Australian Aboriginal. This hierarchy of representation could be seen as symbolising the hierarchy of Australia's prevailing social and artistic values where industry, sex and popular culture are valued most while indigenous culture, social politics and the nature environment are at the bottom rung of this 'values' ladder. Whilst operating outside mainstream art circuits can afflict economic hardship and delay public acclaim, this isolating and peripheral position is also recognized as a fertile ground for creative vision as illustrated here by a reflection on the life and work of philosopher David Hume; 'Even occasional disappointments, such as his failure to secure a university professorship, usually served to preserved in him the unremitting independence of mind and breadth of interest which are among his most salient characteristics' (Aiken, 1948, p. ix). The confinements of the urban establishment itself is often self absorbed and limited to the human conditions in itself, this also might endow rural art with special creative vision;

The breadth of vision of the un-urban artist can be seen as significantly broader than his fellow city dweller, not only because of the physical and practical demands and opportunities posed by negotiating a much larger environmental and social exposure but also due to lesser interference from a market orientated art culture. The tradition of Australian art and photography has had a long association with rural Australia and its bush settings, however, the majority of its production in the twentieth century has been the fruits of the artist venturing from their city habitat to the bush for the purpose of self discovery or artistic development, an experience limited in time and space. This phenomenon is evident in the work of acclaimed photographers such as David Moore, Dupain and Hurley, and in the work of painters such as Sydney Nolan, Tim Stonier and Arthur Boyd. This point is also demonstrated in the legacy of the Hill End art colony. While this kind of landscape art can be seen as part of a venerable practice of expedition photography, the pleirtair movement and its artists' camps (Topliss, H. 1984, p. 11), or part of the tourism genre, so can its content be viewed to represent a voyeur's observation whereby lacking in knowledge of continual processes and intimate understanding of the place and its various elements. Dwelling in a rural or natural environment has obvious relevancy to the field of landscape photography as it might offer an intimate, personal knowledge of the open landscape and its people, a depth of understanding that city dwellers might not easily attain. The impact of marginalisation might therefore influence the photography of Stacey by sharpening its political and social perspective, which in turn is exacerbated by the restricted access to distribution and exchange of consumption resulting in a reduced economy. This predicament of life in the rural parts of Australia is similarly shared by photographer John Rhodes, a man of similar age to Stacey whose photographic career was sustained by the support of Australian cultural institutions and their favourable view towards the production of Aboriginal-related projects during the 1970s and 80s, a fact that at times determined his photographic output.

The 1990s

|

• photo-web • photography • australia • asia pacific • landscape • heritage •

• exhibitions • news • portraiture • biographies • urban • city • views • articles • • portfolios • history •

• contemporary • links • research • international • art • Paul Costigan • Gael Newton •