|

John Thomson: Photographer in the Straits Settlements

Gael Newton AM

2025 revised version of the 2018 essay for the Peranakn Museum’s catalogue: Amek Gambar: Peranakans and Photography

|

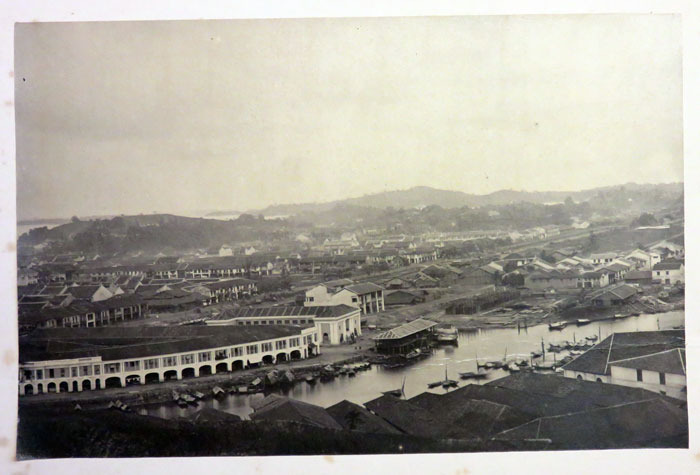

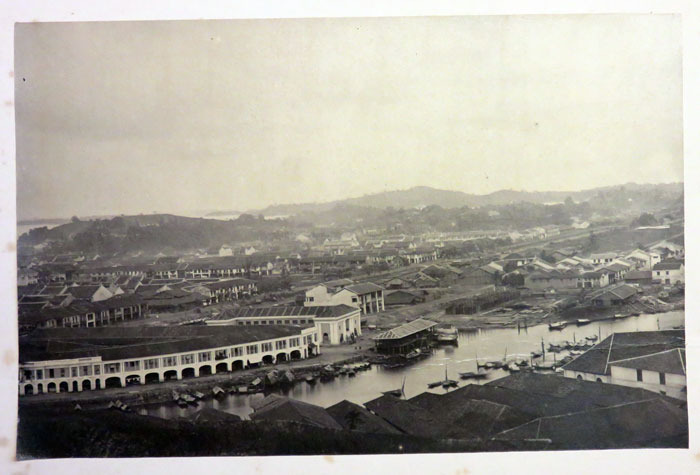

# 01: John Thomson, View of Boat Quay c 1863, albumen silver photograph possibly from a panorama

Lee Kip Lee collection |

John Thomson and photography

Optician turned photographer, writer, and photobook publisher John Thomson (1837-1921) is one of the most fascinating Scottish artisans to have travelled to Asia in the mid to late 19th century.

From his professional start in Singapore at Thomson Brothers’ studio in 1862 to his last assignment as a travel photographer in China in 1872, Thomson took some of the earliest surviving photographs of The Straits Settlements, Thailand, Cambodia, China, Vietnam, and Taiwan (fig. I).1

Thomson’s vision for the medium of photography in its early years was not just topographical, it was ethnographic as well as modern. Thomson’s publication of his photographs and writings in a range of magazines, books, and his lantern-slide lectures brought him international fame as a camera artist, recognition as a geographer from learned societies and financial reward.

He was more of an observer of people and cultures than one of landscape or antiquities.

|

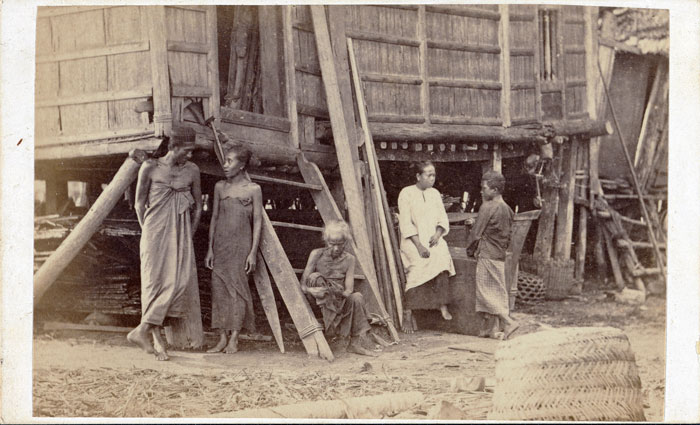

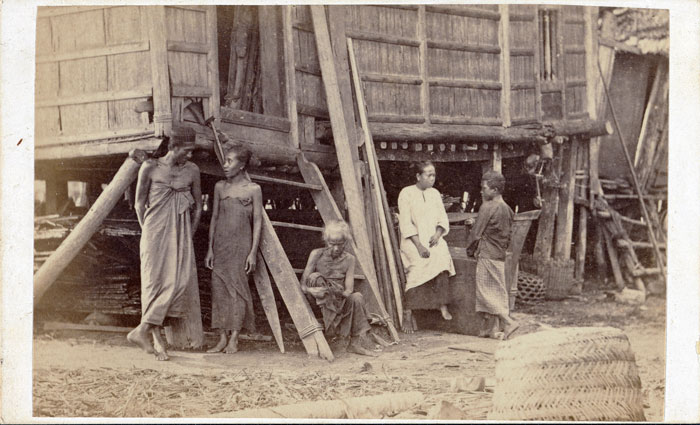

#02: Thomson Singapore, Malay Huts ca. 1862-1864, albumen silver carte de visite photograph

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Gift of the Hall Family Foundation |

| |

|

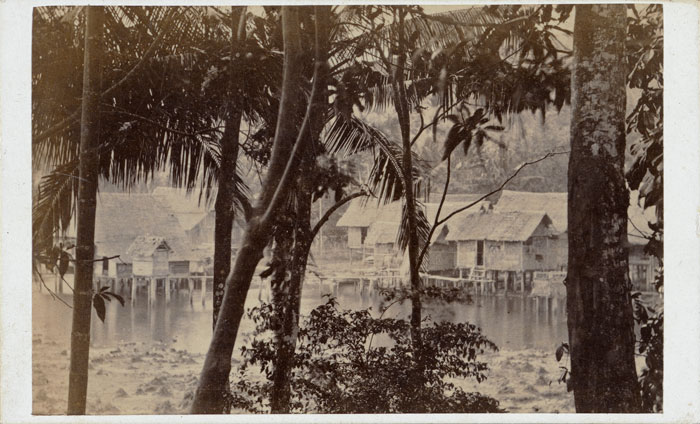

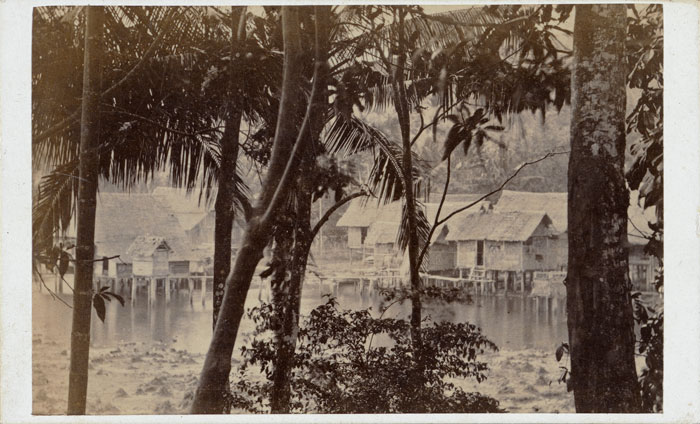

#03: Thomson Singapore, Malay Huts ca. 1862-1864, albumen silver carte de visite photograph

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Gift of the Hall Family Foundation |

Today John Thomson is rightly celebrated in photo history as an innovator in the genre of documentary street photography and photobook publication. He was primed by his progressive ‘Mechanics Institute’ education in Edinburgh. He was also influenced by the intellectual climate of the early nineteenth-century Scottish Enlightenment’s interest in evolution to develop the medium’s social application to the visual study of landscapes, cultures, and peoples (figs. 2, 3).2

In 1875, Thomson reputedly held that 'the camera should be a power in this age of instruction for the instruction of the age'.3

To achieve that enlightened democratic aim for photography, during the period 1867–1898, Thomson disseminated his texts and pictures through the rapidly developing technologies of photographically illustrated magazines and books. This was different from the popular at the time sales of albums with original prints bought by affluent tourists and armchair travellers.

Thomson’s international fame came first through the publication of his deluxe four-volume Illustrations of China and its people (1873-1874) and later through his urban ethnographic study Street Life in London (1877-1878) with socialist journalist Adolphe Smith (1846-1924).

Both are regarded as landmarks in the development of the mid 19th century mode of 'learning-by-looking', which became the photojournalism of the twentieth century. Thomson’s popular 1875 compendium The Straits of Malacca, Indochina, and China; or Ten Years’ Travels, Adventures, and Residence Abroad was targeted at an audience who could not afford his earlier works. It provides the only narrative of Thomson’s time at the outset of his career in the Straits Settlements.4

Thomson’s 1898 Through China with a Camera, an abbreviation of his earlier books, made use of the new and cheaper half tone process, in which “nothing in the original plates is lost”.5

In his later life, Thomson visited the first public exhibition at the museum in London established by pharmaceutical entrepreneur and collector Henry Wellcome in 1913. Noting the lack of photographs, Thomson offered the museum’s curator his negative collection, pointing out that 'Each photograph was taken to represent something peculiar to the lands and to the people visited. Each series includes antiquities, arts, architecture, industries and evidence oi evolution'.6

Thomson died before the acquisition was finalised. The digitised negative collection is available on the website of the Wellcome Library (a part of the Wellcome Trust founded by Henry Wellcome).7

Thomson would have been delighted with this arrangement.

Thomson in Singapore

What is less known is that Thomson’s style of social photography first appears in the images he made on the streets of Singapore, Penang and Province Wellesley in the early 1860s. This obscurity is largely because the Straits Settlements negatives are not part of the Wellcome Library collection.

That inventory remained in Singapore and was passed on to a succession of owners after Thomson Brothers and its studio contents were sold in 1870.8 The negatives probably ended up dispersed, dumped, or salvaged for their glass. Modern histories of photography must be built on the fragmentary remains of 19th century photography studios.

The survival of Thomson’s Asian negatives at the Wellcome Library has ensured several new lives for his work in the late twentieth and early 21st century as interest in China has grown. The loss of the Straits Settlements negatives proves significant as the numbers of extant photographic prints by Thomson of the Straits Settlements are surprisingly small, perhaps under two hundred.9

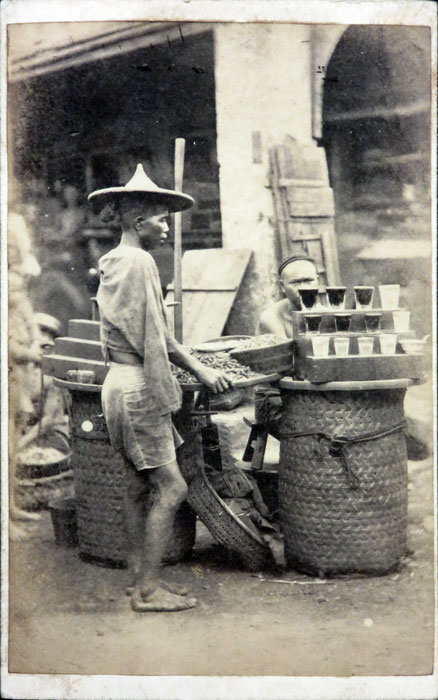

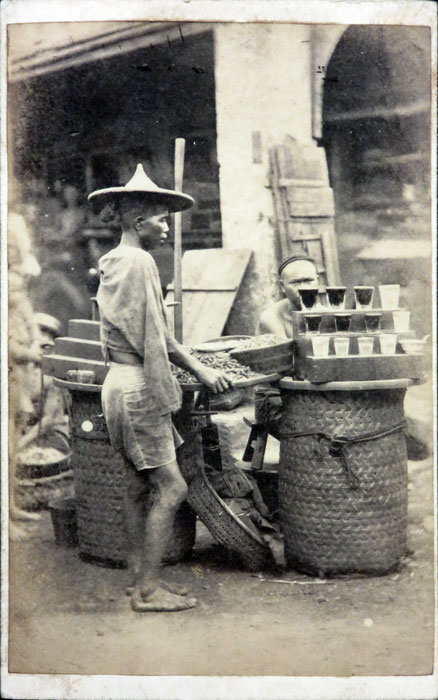

But within that cache it is the prints and miniature cartes de visite of the local multi-ethnic communities taken in the studio and more important out on the streets that reveal Thomson’s evolution as a travel photographer and proto-photojournalist (fig. 4). |

|

|

#04: Thomson Singapore, Sweet water seller Penang or Singapore c 1863, albumen silver carte de visite photograph

Lee Kip Lee collection |

|

John Thomson came from a comfortable Edinburgh tobacco merchant’s family and like his elder brother William, a watchmaker, was apprenticed around 1851 to an optician and instrument maker. He graduated in 1859 from the Watt Institution and School of Arts in Edinburgh where he underwent some artistic training in addition to honing his technical drawing skills.

In 1860 Thomson was accepted as a member of the Royal Scottish Society of Arts, a learned society in Scotland dedicated to the study of science and technology. He had been nominated by optician and instrument-maker James Mackay Bryson (1824-1866) who was an expert microscopist, wet-plate process photographer and member of the Photographic Society of Scotland. Thomson might have learned photography from Bryson although Edinburgh was very well supplied with photographers and had a commercial School of Photography in I860.10

There is no record of Thomson training or working in photography in Edinburgh, but he was experimenting with various processes by 1859.11 Upon his arrival in Singapore in June 1862, he confidently advertised his services as a professional photographer with specialties of microscopic copying of cartes de visite for lockets and stereographs.

Thomson had come to join his brother William who since 1859 had been operating as a watchmaker and marine instrument maker in partnership with Captain W. C Leisk, a successful Scottish marine surveyor and purveyor of chronometers. William had been offering a photography studio service at Beach Road under the name Sack & Thomson and subsequently on his own.

So little fuss was made about the arrival of the new, easily reproducible, wet-plate photography in Singapore in the late 1850s and early 60s that we can assume residents were already well aware of photography including novelties like the miniature carte-de-visite portraits from imported examples, newspapers, and traveller’s reports.

The newspapers are silent on how locals felt about seeing their first personal portraits (fig. 5). We do not know either how successful William had been with his photographic service.12 |

|

|

#05: Thomson Bros,Portrait of Miss H. Simons and Singaporean woman c 1863, albumen silver carte de visite photograph, Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, Launceston, Tasmania, Gift of Henry Armitage 1967, Henry Minchin Simons was a principal and director of Paterson Simons & Co |

|

Soon after John Thomson’s arrival the brothers’ joint photography studio was established and located at the busy Battery Road commercial centre along the Singapore River. A few photographers had passed through or operated in Singapore since 1845, so for a brief period in 1862 the Thomson Brothers were the only photographic service in town.13

For a man who wrote and spoke much about his career, Thomson’s personal information is scant. His transition to a new vocation as a photographer appears to have had gone smoothly. It would seem business was good for John Thomson as his two initial newspaper advertisements in mid-1862 were not repeated. Word of mouth was sufficient or he was a frugal Scot.14

|

| #06: Thomson Singapore, European woman, Singapore c 1863, albumen silver carte de visite photograph , Lee Kip Lee collection |

|

|

|

| #07: Thomson Singapore, Malay man , albumen silver carte de visite photograph Lee Kip Lee collection |

|

The John Thomson Style

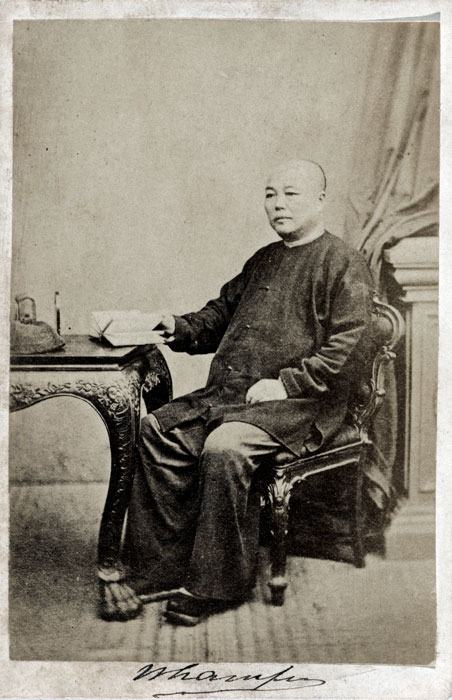

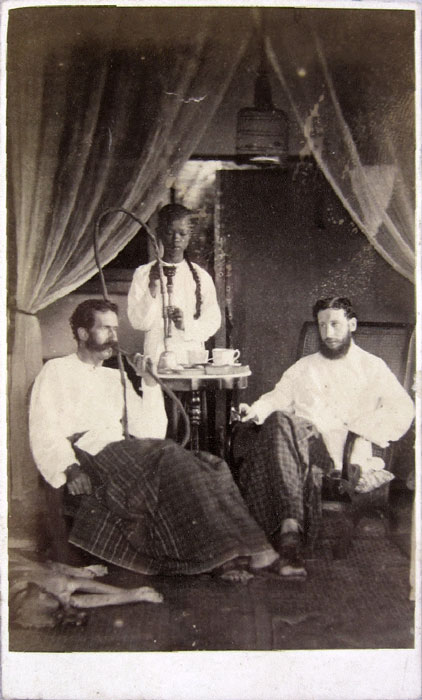

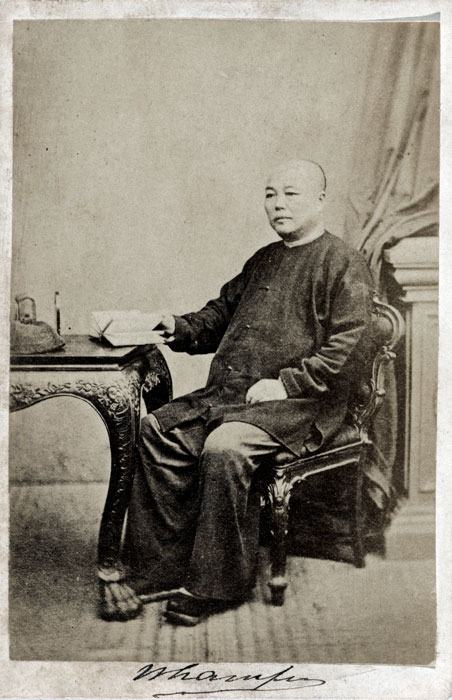

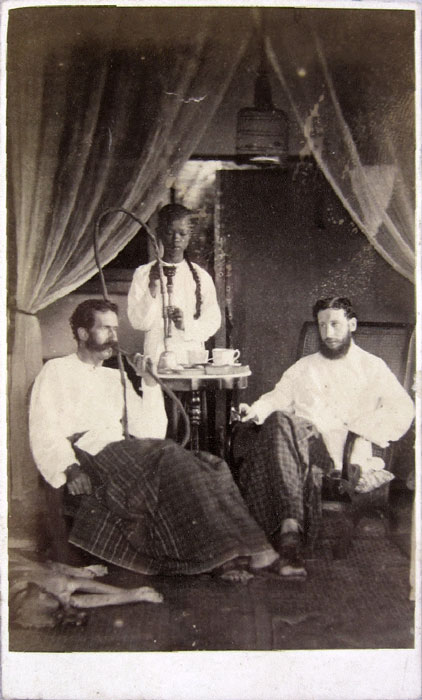

Thomson’s Singapore bust and full figures portraits are expertly made and show his competence (figs. 6 & 7). In addition to elegant portraits of Europeans dressed in their best outfits, Thomson photographed the leading Chinese merchant Hoo Ah Kay (aka “Whampoa”) possibly on commission from the sitter himself who was well-versed in Western ways. Hoo Ah Kay’s portrait appears in various archives and was also sold by Thomson Brothers as an 'exotic type' (fig. 8).

The format in Thomson’s oeuvre with which this essay is concerned is the carte de visite. This was the name for the 1854 French wet-plate format of miniature portrait on a calling card-sized mount that became hugely popular worldwide in the 1860s. For the first time in history easily shared and collected miniature personal likenesses were available to a wide range of the middle and upper classes.

|

| #08: J & W Thomson , Whampoa [Hoo Ah Kay C.M.G aka by honorific ‘Mr Whampoa’] Singapore c 1863, albumen silver carte de visite photograph, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra |

|

|

|

#09: Thomson Singapore , Armenian c 1863

albumen silver carte de visite photograph , Lee Kip Lee collection |

|

The sitters found the studio space to be a kind of theatre in which they could seek or submit to various guises for themselves. The new format changed their self-awareness and also their perceptions of others. Sales of cartes of celebrities, royalty, and exotic races or 'types' were a significant line of income for photographers and stationers.

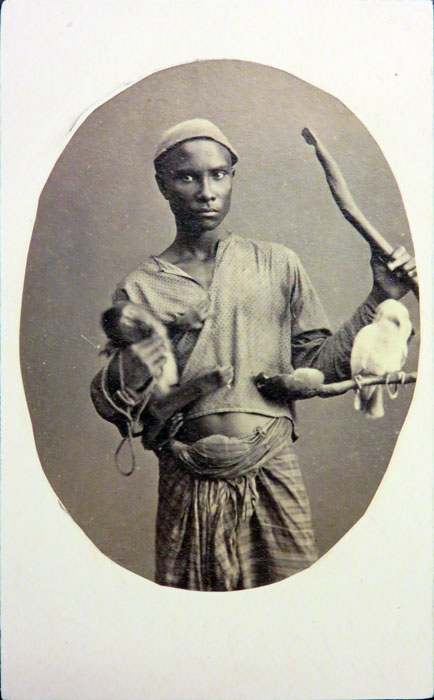

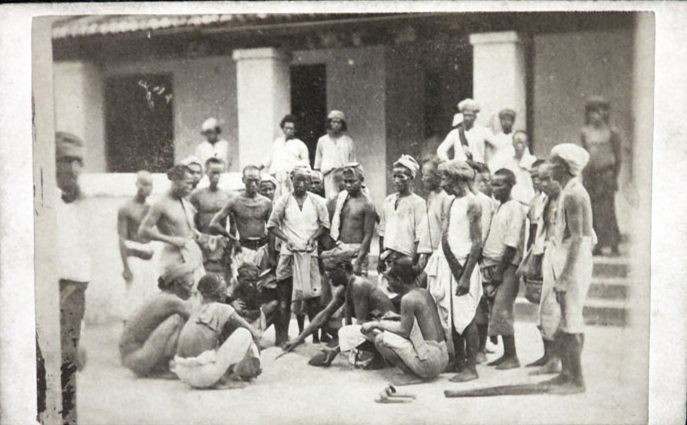

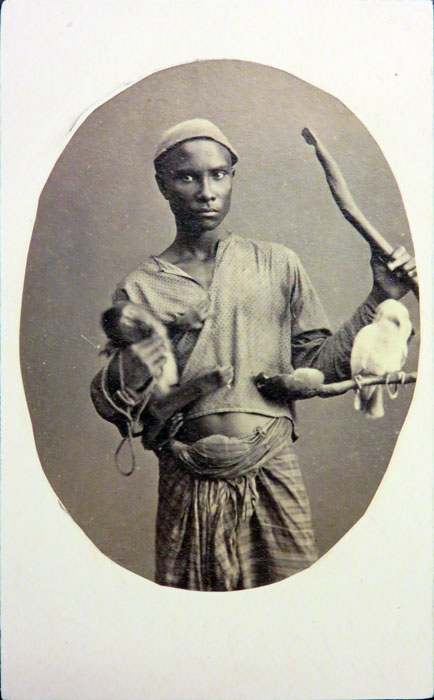

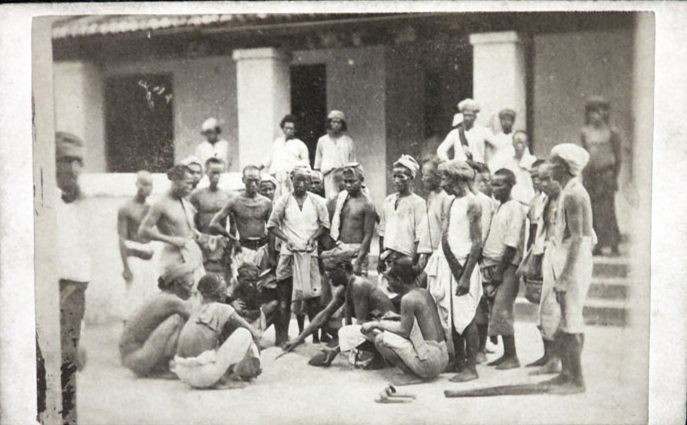

The Thomson Brothers studio cartes include images of dignified Armenians, Malays, and Chinese that may have originated from private commissions (fig. 9). Other cartes are of lower-class Chinese, Malay, Kling, Hindu, Sikh, Burmese, Bugis, Javanese and Vietnamese sitters who appear to have been recruited to pose in the studio (figs. 10 & 11). Their images were sold to the booming tourist and international market for images of exotic peoples.15

|

| #10: Thomson Singapore, Woman in Chinese costume c 1863, albumen silver carte de visite photograph , Lee Kip Lee collection |

|

|

|

| #11: Thomson Singapore, Malay, albumen silver carte de visite photograph, Lee Kip Lee collection |

|

Cartes de visite are generally uniform in posing and backdrop, no matter how remote a location they may have been taken at. Thomson’s portraits have a presence and charm beyond the usual studio production. But portraits walked out the door with the sitters and made few, if any, re-orders.

Views by contrast had multiple sales potential, so Thomson began making forays to Penang and Province Wellesley where as he put it, 'I was chiefly engaged in photography, a congenial, profitable, and instructive occupation, enabling me to gratify my taste for travel and to fill my portfolio'.16

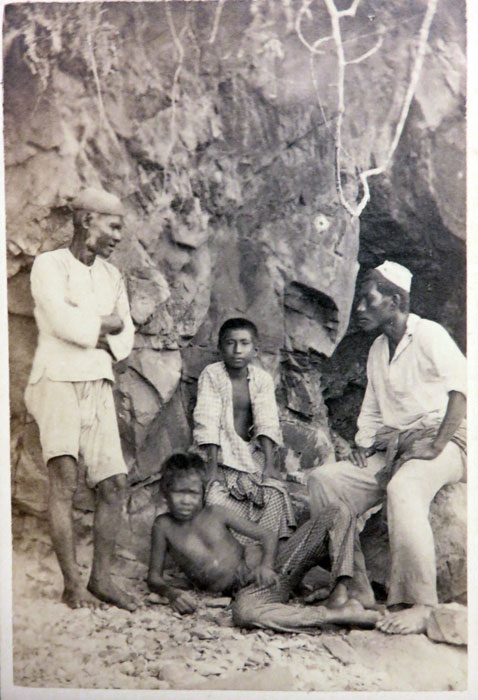

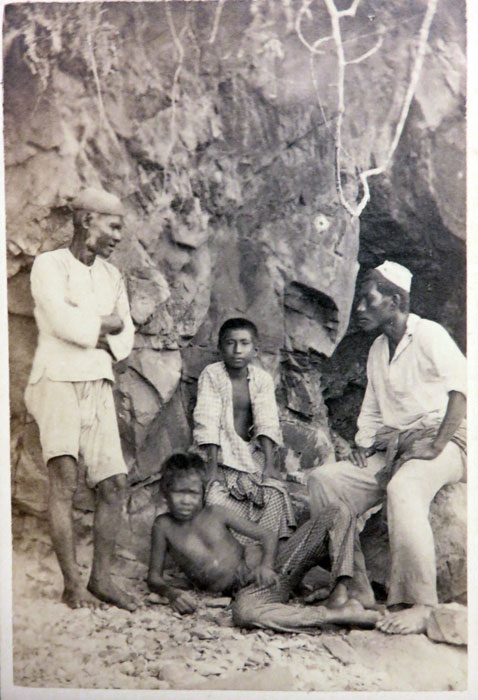

In his landscape images from Penang, Thomson exhibits a gift for placing figures in their tropical environment; a much harder exercise than in the controllable light and fixtures of the studio (fig. 12).

Thomson’s exotic cartes of 'types' appear most regularly in present-day public archives; the commissioned portraits remain only if they have survived in family albums.

It is hoped more examples will come to light to extend the picture of Thomson’s activity in the first phase of his career. |

|

|

| #12: Thomson Bros Indigener de Singapoor c 1863 Penang or Singapore, albumen silver carte de visite photograph , Lee Kip Lee collection |

|

As superb as his topographic photography was, Thomson was not a typical “views” photographer accumulating inventories of pictures for the souvenir trade. His personal interest was in the peoples of foreign lands and their civilisation. His gift in posing and engaging with the people on the streets is evident in his images of the Straits Settlements (fig.13).

These earliest portraits of the Malays reveal how Thomson in these years evolved from a studio-bound portrait photographer to one who embraced documentary photography outdoors and would soon plan a new life as a travel photographer.

Thomson had possibly developed his interest in foreign lands and peoples through his education in Edinburgh. Only at a later stage did he realise that roving travel photography could be a full-time profession. The genre of travel and expedition photography was also gaining respect for the medium from learned geographic and ethnographic societies. Thomson departed Singapore in 1865 for Hong Kong and ever more ambitious travels to discover antiquities, exotic courts, and peoples of Thailand, Cambodia, and China.

|

| #13: Thomson Bros , Convicts Penang c 1863, albumen silver carte de visite photograph , Lee Kip Lee collection |

Singapore where it began

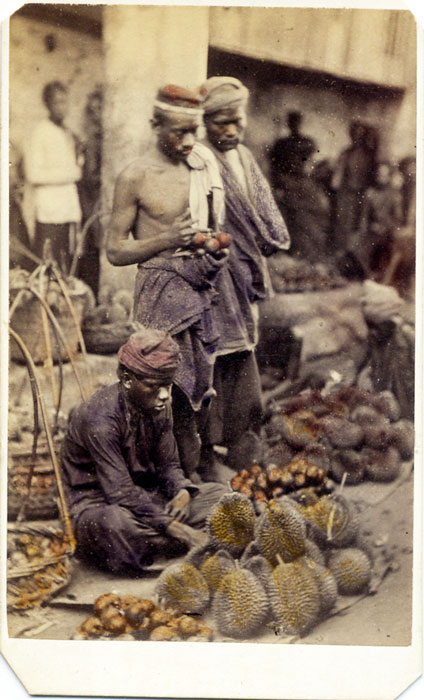

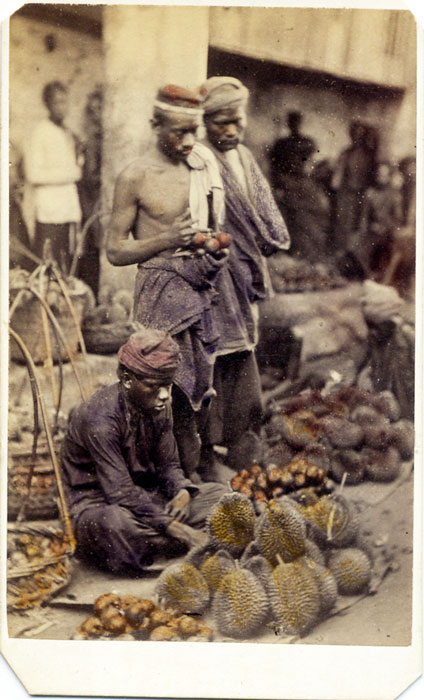

The key images for Thomson’s evolution as a travel photographer are the surviving images made on the streets of Singapore and Penang. A favourite image that Thomson used in his 1875 book The Straits of Malacca, featuring Malay boys selling durians and mangosteens (fig.14), also appears in various collections and publications.

The image looks spontaneous. But the fruit sellers are posed and the onlookers in the background are watching on with interest. For those who know Singaporean hawkers, the image remains very evocative. Other images show groups of locals skilfully posed and directed in the lush tropical landscape. Possibly the two Madras assistants he hired in Penang are the models in some of those images.

These portraits taken in the Straits Settlements precede the street portraits Thomson would make in China in the 1870s and much later his social documentation of shopkeepers and street sellers in London in 1876.

The lack of competition Thomson found on first arrival in Singapore in 1862 did not last. German telegraphist- turned-photographer August Sachtler arrived in 1863. Over the next decade Sachtler built the first extensive quality photographic record of the Straits Settlements and its nearby regions. In contrast with the energetic Sachtler, Thomson rarely advertised or competed with other studios in making panoramas and commercial albums. He did not seek prizes at international exhibitions that served as a showcase for the average mid-to-late 19th century commercial studio photographer.

|

| #14: Thomson Singapore Durian sellers c 1863, albumen silver carte de visite photograph , Lee Kip Lee collection |

|

|

|

| #15: Thomson Singapore, Portrait of Colonel Dana T. McClarrity ca. 1862-1864, albumen silver carte de visite photograph The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Gift of the Hall Family Foundation |

|

The John Thomson legacy

By 1865 Thomson had decided to search out the most exotic antiquities and societies, and feature them in a systematic way. Over time he became more determined to publish them in the tradition of the expedition narrative like those from the Golden Age of Exploration but in a more accessible, journalistic style.

He photographed in Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Taiwan and spent four years in China before returning to Britain in 1872. He was preeminent as a pioneer systematic photojournalist in Asia.

Thomson’s post-Asia career phase saw him return to portraiture. He ran a London high society studio from 1881 until his retirement in 1910 when he returned to Edinburgh. He continued with various writing and lecturing roles from 1886 to 1889, instructing would-be explorers in photography at the Royal Geographic Society and occasionally making portraits of famous explorers. Thomson’s literary ability and engagement in mass communication ensured his legacy.

While so much of Thomson’s formative work in the Straits Settlements is lost, what remains for our instruction and pleasure is a small cache of elegant and lively images (fig.15). What is more significant is the knowledge that it was in Singapore and Penang that he discovered how to capture images of life and landscape and possibly even foresaw how he could marry these to the modern world of global publication though illustrated travel books.

|

#16: back of #02 above, Lee Kip Lee collection.

The chronology of the Thomson studio logos has not been established. Images of Thailand, Indochina and China also appear on Thomson Singapore imprints. |

|

|

|

| #17: Back of #09 |

|

Notes

- Biographic details of Thomson’s education and early career in the Straits Settlements are taken from Montague and Mizerski 2014, pp. 5-22. For the carte de visite focus of this essay, see references to the Janet Lehr collection of Thomson’s Asian cartes de visite, op. cit., pp. 88-95.

- Between 1856-58, Thomson studied natural philosophy, chemistry, and mathematics at the Watt Institution and School of Arts, founded in 1821, in Edinburgh, the world's first Mechanics’ Institute for working-class artisans and technical workers. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heriot- Watt_University.

- Unsourced quote cited by curator Robert A. Sobieszek in White 1985, p. 7, a major monograph on Thomson. The quote has been popular with subsequent writers, but the source has not been identified.

- Thomson 1875. The woodcut illustration of the Straits Settlements in this publication must have been based on the prints Thomson kept with him after leaving Singapore as a base in 1865, as the negatives were left behind, see note 8 below.

- Thomson 1898, p. IX.

- Letter of 12 May 1920, cited on website of the Wellcome Trust, London https://wellcomecollection. org/articles/john-thomsons- china-O. Accessed 18 May 2018. See https://wellcomelibrary.org/ collections/digital-collections/ john-thomson-photographs.

- “Thomson Brothers chronometer, optical and nautical instrument makers”, in Battery Road, was taken over on 15 June 1870 by J. S. Leisk, see Straits Times,

- September 1870, p. 3. On the same page, J. G. Davidson, Trustee, advertised the sale of “Photographic apparatus including negatives of the Estate [sic] of Thomson Brothers" as of 13 August 1870.

- The largest holding of Straits Settlements prints by or attributed to John Thomson is found in Mr and Mrs Lee Kip Lee's private collection in Singapore. Small groups of Thomson’s prints and cartes are held by National Library, Singapore, and the National Museum of Singapore. There are about 30 12 prints and cartes in the John Thomson collection at the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum (provenance: Stephen White); about 14 cartes in 13 the Janet Lehr Fine Arts collection in New York; 13 “Thomson Singapore” imprint cartes are held at the National Gallery Scotland; 8 prints at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri; and 8 prints in an album dated November 1863 held at the University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Special Collections and University Archives. Straits Settlement, 15 prints or cartes may also be held in the John Thomson holdings of the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts.

- The Edinburgh School of Photography in Nicholson Square was opened by French professional Andre Orange at the suggestion of the Photographic Society of Scotland. See Caledonian Mercury, 18 August 1860, p. 1. Orange was skilled in stereophotography and was most likely an early user of the carte de visite. See Andre Orange’s biographical entry at http://www.edinphoto.org.uk/pp_n/ 16 pp_orange.htm.

- Thomson is listed as an optician in the 1861 British census. He did not join the Photographic Society, but on his first visit home in December 1866, he gave members a lantern- slide lecture on the scenery, architecture, and people of Siam and Cambodia. Where and when Thomson gained fluency in French, as seen in his role as a translator of several French photographic texts in later years, is unknown. There are strong connections in Edinburgh between the eighteenth- century Scottish Enlightenment and the French philosophers that may well have influenced John Thomson’s views of Asian society.

- Sack’s identity is unknown, and no examples of William’s or their standard of portraiture are known.

- For an introduction to the first generation of photographers, see Toh 2009.

- Nineteenth-century photographers are usually tracked through their numerous newspaper advertisements, but neither Thomson brothers, nor John on his own account, made use of this form of promotion.

- Attributed to the Thomson Brothers are cartes with the studio stamps - “Thomson Bros Singapore”, “W & J Thomson Singapore”, or “Thomson Singapore” imprinted on the back (figs. 16.17). A chronology of these has yet to be determined. It is not clear from these imprints either what role William played over time in the Thomson Brothers’ service up to his own departure from Singapore in 1870. The brothers had employed assistants and possibly a camera operator to run the day-to-day walk-in portrait business.

- Thomson 1875, p. 8. This line reveals the real motivation for his career change from the prospect of a life spent at a workbench as an optician.

more on John Thomson

|