|

Leo Haks:

Collecting Indonesian photography 1860s-1940s

This text is based on notes supplied by Leo Haks when he was selling his collection to the National Gallery of Australia in 2007. The text includes some information on Leo’s background and information as supplied by Leo on the photographers in that collection. Those notes highlight some of the gems that entered in National Gallery of Australia’s collection in 2007.

Leo Haks was born in Zeist, the Netherlands in 1940. He passed away on January 30, 2021 in Nelson, New Zealand

In the collection Leo assembled over a 30-year period, he tried to show Indonesia as it was between about 1860 and 1940. Staying away from the colonists and their direct influence on the country, Leo placed most emphasis on the Indonesian people, their culture and the landscape, without concentrating on portraiture per se.

Leo wrote that his photography collection was never the end result of a drive to collect in the conventional sense. It was more accidental than intentional; the result of circumstance and opportunity instead of planning and execution.

Leo considered the collection’s location in Australia would see it being used by scholars of different disciplines so as to gain a better understanding of Indonesia, its closest neighbour, to their mutual and lasting benefit. The prospect of this happening made the parting of the collection a happy rather than sad event.

Leo wished the National Gallery of Australia will long cherish the guardianship of his much-loved collection.

Background

On his 13th birthday his parents presented him with a Baldixette, a simple but for the time acceptable 6 x 6 cm camera. In 2007 he still had that camera which remained operational.

The first pictures he took were 5 close-up shots of swans in his neighbourhood pond and they remained in his archive. Both photography and birds remained prominent areas of interest throughout his life. As he grew older, Leo did not photograph birds, rather he observed birds through binoculars or the naked eye rather than through a camera lens. He came to the view that in those circumstances the camera was too much of a distraction.

In 1968 Leo settled in Singapore, working for a food-based company. For him it was work without much personal gratification. In 1977, he became Managing Director of ‘Apa Productions’, a Singapore based publisher of the photography oriented ‘Insight Guides’ series. It was the photography aspect that particularly interested him.

During this time until 1982, he made contact with many photographers and learned about photography; with the result being that he became an amateur photographer. The equipment changed from the old box, to more up-market 35mm or digital cameras, although he preferred the larger size negatives for their potential sharpness in enlargements.

|

In a second-hand book shop in The Hague whilst visiting Holland in October 1977, Leo found a photograph album by P. Klier of Rangoon. It was not dated but he already knew this had to be from the last quarter of the 19th century. He loved the album at first sight and purchased it. Fifty guilders for 60 fine prints seemed a bargain he could not resist. That album remained his most precious possession in the collection. Leo credited it as being something that made him look at photography with different eyes.

Returning to Holland in 1984, Leo began collecting photographs more seriously. Having had some exposure to Indonesia during his Singapore stay, he established an antiquarian book business, specialising in early books on Indonesia. He did not cater for Dutch people, but instead to Indonesian and non-Indonesian clients living in Indonesia. His specialisation was 19th century plate books.

Leo’s view was that the Dutch had colonised Indonesia for 350 years and even if they contributed little to the development of the country and, as history shows, even less to its people, at least a good number of scholarly and less scholarly books were published over the years. Many of the colonists had returned to Holland after Indonesia’s independence in 1945. Others had returned home prior to that.

Consequently, sourcing was made relatively simple as there seemed to be an abundance of supply. The reality showed this not to be the case, as by the late 1990s, supplies began to run low and almost dried up. As the older generation of returned Dutch colonists died, all too often, there were no interested relatives to look after their libraries, which were subsequently sent off to be sold at book auctions. These libraries often included photo albums and / or individual photographs. Some of these subjects Leo was not attracted to such as massacres, official colonial subjects and many more. In that sense the Leo Haks collection became quite personal in its scope.

Collecting by subject was rewarded in 1994, when Leo met Scott Merrillees, a Melbourne resident, who was researching the topography of early Batavia, now Jakarta. Leo sold Scott the Batavia material that went on to form a good part of Scott’s book ‘Batavia in 19th Century Photographs’.

Leo considered it was a very purposeful transaction as he considered Scott’s book admirably displayed a depth of knowledge well beyond Leo’s. The sale of the Batavia section was to finance a book that Guus Maris, Leo’s then business partner were compiling. Being a rather esoteric book, they had to self-finance the ‘Lexicon of Foreign Artists who visualised Indonesia, 1600 - I960’. Guus and Leo decided there was too little known or published about Indonesian photography to risk their inclusion. They saw the irony in this, as who would have visualised Indonesia better than photographers?

To keep up to date on photograph prices, Leo subscribed to worldwide photographic art auction catalogues of Christie’s, Sotheby’s and others as well as book auctions, including specialist sessions on Travel and Exploration and Natural History. It was from the latter auctions that Leo purchased more and higher quality items than from the photography sales.

Features of the collection

The majority of the photographs in the collection were made by photographers who were settled in Indonesia and running commercial photo studios there.

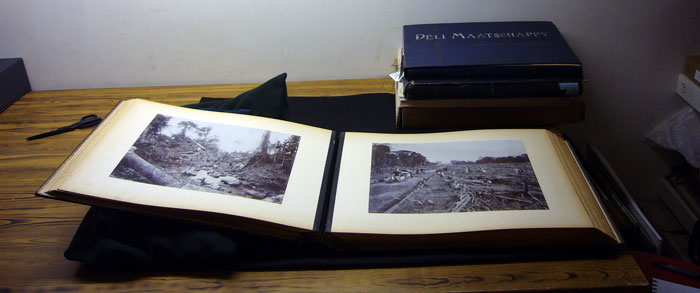

The photographs were mostly documentary in nature. Their purpose varied considerably: Many were commissioned pieces; e.g. factory details, plantations, portraits, townscapes and many landscapes. These photos were often pasted in albums by the photographic studio. This made the albums beautiful objects in their own right. Very early albums are as rare as they had always been, because the images were expensive to purchase.

A returning colonial bringing an album with photographs of where he had lived or worked, was enthusiastically received back home. Because original photographs were uncommon for most people to have seen in those early days, let alone those from exotic countries. |

|

|

| Personal albums |

|

|

These took different forms at different times. The earliest albums comprised professional photographs selected by individuals mostly from stock photography. In more affluent families photographs of the family and their living surroundings were commissioned.

By the beginning of the 20th century, cameras had become affordable for amateur photographers who delighted in the immediate recording of family life, which was sometimes supplemented in the albums by the work of professional photographers.

Many of these albums were taken home to the Netherlands or other countries to show relatives and friends where they lived and what ‘Our Indies' looked like. These documents were very special, since in the second half of the 19th century the distribution of photography was still in its infancy. |

|

|

Corporate albums

Corporations likewise had their enterprises photographed so that they could be shown to potential investors and / or clients. These became the more elaborate albums as witnessed by the Kleingrothe and Kurkdjian albums in the Haks collection.

Many photographs were taken during the so-called Transition period 1945 - 1951 when the Dutch unsuccessfully tried to maintain their hold over Indonesia. Leo had collected photographs from that period but, since that was outside the scope of his usual collecting, he sold a collection of over 25,000 photographs to an Indonesian foundation. The vast majority of these were taken by amateur photographers.

Academic/Research photographers

What may well be the most interesting group of early Indonesian photographs were those taken by professionals in other fields who used photography to assist in their research. One of the earliest such persons was Dr. Franz Wilhelm Junghuhn. (1809 - 1864). Junghuhn, a German doctor and scientist, is recorded to have purchased a complete set of photographic stereo equipment as early as 1860 and used it during the same year. Junghuhn produced his famous lithographs of Javanese volcanoes and landscapes prior to his photography.

In that way, he was similar to the Reverend John Kinder, who had produced similar lithographs, but of New Zealand landscapes. Kinder also purchased a set of stereo equipment in 1860. It seems that whereas Junghuhn printed both images of the stereo photos, Kinder seems to have encountered difficulty or lack of time to do so and mostly printed one of the two images only.

The out-sized panorama photographs of New Guinea by anthropologist C.C.F.M. le Roux, are an exceptional testament to the academic/ photographer. Housed in the collection of the Tropen museum in Amsterdam, they illustrate that a professional attitude can be readily extended to different disciplines. Le Roux’s work belongs to the highlights of Indonesia’s photographic heritage.

Bali especially, became a mecca for academics, tourists and students of the exotic. Lois Bateson, widow of anthropologist Gregory Bateson, told Leo that Bateson took some 12,000 photographs during his stay in Bali from 1936-1938. His books on the subject of Bali corroborate his active interest in photography.

Many others came to Indonesia for research of one kind or another. Botanists, ethnographers, geologists, (mining industry) anthropologists and specialists in many other sciences or disciplines supported their research with their own photography.

Working mostly for universities or other institutions of learning or research, this is a very special body of work. Being specialists in their respective fields, they knew the most opportune moment to take a picture of a dance, exorcism, weaving or any other activity.

Much of the work of these people went to their respective universities or institutions and their photographs were printed in limited numbers and were used for research purposes. Their photographs or negatives were usually archived in their institutions and hence, to survey the entire photographic history of Indonesia would take one to many locations.

Finally on this subject, these photographers would, by the nature of their work, travel to out of the way locations where, often enough, no other westerners had ever set foot. The photographs of Frank Hurley in Papua New Guinea come to mind, even if that was not in Indonesia. However, in the Mitchell library in Sydney there is a small group of large size prints that Hurley took in Java. Leo considered that these Hurley photographs ranked among the finest Indonesian photographs he had seen.

Elio Modigliani’s photographs of Nias and Engano taken during the 1890s are similarly striking and important. EEWG Schröder’s ‘Nias’ of 1917 shows how beautifully a scientist can capture the subject of his interest.

Not to be overlooked are the Land Surveyors. They photographed extensively to record the typography. Jean Demmeni is a fine example. Initially he worked for the topographical service of the military until his retirement. Later he was hired by the civilian branch of the same service. Demmeni also photographed outside of his working brief.

Hak’s book on Demmeni was published in 1987 but later research showed many images were by other photographers.

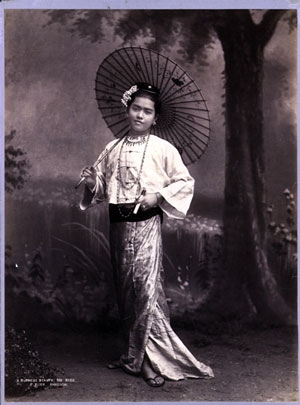

Studio and portrait work

Their work seems also to have been favoured by the local aristocracy. Whether this was politically motivated or not remained unclear to Leo. In album Ref. # 5138 there is a photo of a train carriage with the notice ‘inlanders’, a qualification Haks did not believe was applicable to Chinese people. Even today, Chinese people are less privileged citizens in Indonesia. As a footnote to this little chapter, it must be said that the Chinese were very much greater in number than the Japanese at that time and had already been settled there for generations.

German photographers

Unlikely as it may seem, there have been a large number of German photographers active in Indonesia from the early days. The first photographs of Indonesia ever recorded are the daguerreotypes by Adolph Schaefer, Tassilo Adam, among many others who were also active in Java. G. Krause was in Bali and Borneo. In Sumatra especially, their number was disproportionately large. G.R. Lambert, C.L. Kleingrothe, H. Ernst, H. Stafhell were all active there at some time or another.

Leo had no explanation for the high number of German photographers at this time, but a similar situation prevailed with veterinary surgeons, the majority of which were German. The surgeons were employed by the armed forces to look after the artillery horses which were used in great numbers.

Dutch photographers

Of the best-known photographers to have worked in Indonesia, few were Dutch. C. Nieuwenhuis being one of the exceptions, especially in the 19th. Century.

Female photographers

Other than Thilly Weissenborn, an Indonesian born Dutch woman, Leo did not recall any other professional female photographers who worked in Indonesia during the period 1860s- 1940s.

Amateur photographers

Last but not least, there are the amateur photographers. A large group; the quality of which must be considered of mixed merit. Amateur photography did not commence until early in the 20th century. Leo would exclude Dr. Junghuhn and his ilk as amateurs.

The amateur pictures have a different place in the collection. They tell a story that the studio photographers could not tell; a more intimate one. When purchasing the first family albums, Leo was surprised to see that families were willing to sell their visual histories. It was interesting to see how these families presented themselves when the pictures were taken.

As photographs, few had much merit, but Leo soon realised that although albums hold little interest individually, collectively they become a social history database of significance. From albums, one can read the dress code of the day as well as the interior design of their homes, where the families went on holidays, how they relaxed or related to their servants and very much more. Several researchers have already made good use of that section of the collection.

There is one photo in the collection which is probably an amateur photograph. It is of a Eurasian family at an ‘out-door’ lunch. The man of the household has a pony standing on a fully dressed table with 2 ladies and 2 children sitting around it as if ready to begin lunch! (ref. # 5139). That album shows other purposeful uses being made of horse power from delivery services to garbage collection and more.

As an aside, Indonesian people on the whole do not like to be photographed. The reason is complicated, but Leo learnt that taking photographs is synonymous with the taking away of part of their soul. That seems to explain why one rarely sees an Indonesian smile in photographs. They appear as ‘neutral’ as they can.

Hand coloured photos

There is one such photo in the collection, ref# 5625. It dates from the turn of the 19th to 20th century and is the work of Sem Cephas, son of Kassian Cephas. Being taken by a native Indonesian makes this photograph all the more important. Contrary to worldwide practice at the time, very few hand painted photos of Indonesia from that period are known.

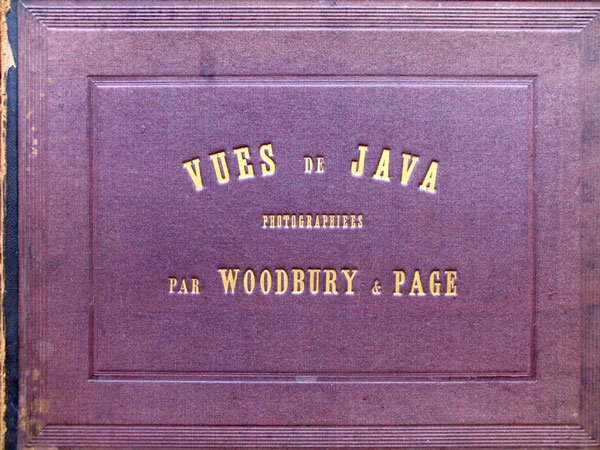

Stereo photos

Besides the stereo photos earlier referred to, both Woodbury & Page and Kurkdjian produced stereo slides on glass plates in 4 x 5 inch size. The earliest of these are of Javanese royalty and were arguably taken by Walter Bentley Woodbury himself.

A small number of these are in the collection of Mr. Wim van Keulen in Haarlem. They are of exceptionally fine quality and are treasures of Indonesian photography.

These slides were duplicated and marketed by Negretti and Zambra in London in 1861. The original images were almost certainly taken before 1860. A hardcopy print from the same shoot is in the collection; four female dancers at the court of Yogyakarta. Here the dancers are sitting while, in the stereo slides, the same dancers are standing. Kurkdjian studio also made stereo photos, some of which are glass plate, others are printed versions.

Around 1900, stereo cards of many subjects were published on Indonesia. Keystone, Underwood, Ingersoll and other publishers are represented in the collection. These are ‘samples only’ as Leo did not make a point of collecting them.

Cartes de visit, and cabinet cards were common from the earliest dates. Like stereo cards, Leo did not afford them much attention and certainly did not collect them, except for a limited number as examples of type. This is mostly on account of them largely portraying Europeans. Since many of these cards have the photographers’ names and addresses printed on them, they are useful for attributing anonymous photos.

Lantern slides do exist from the period and reference can be made to a catalogue listing over 12,000 such slides in the Koloniaal Museum, now the Tropen Museum.

Photo engraving

A complex procedure, whereby a photograph was copied in pencil onto paper and subsequently engraved onto a metal plate to be printed on a press.

Some of the earliest photographs on Indonesia were reproduced in this manner to illustrate printed articles. ‘Le Tour de Monde’ published an account in 1864, by the artist J. de Moulin, who had travelled through Java from 1859-1861. One wonders if de Moulin purchased the accompanying photographs to illustrate his article when he was in Indonesia, or did ‘Le Tour de Monde’ obtain them from a Paris based archive?

What is clear, is that several of the photos in de Moulins article were taken by the Belgian photographer Isidore van Kinsbergen. The dates of de Moulin’s travel and the publishing date of the article leaves the question - when were the initial photographs actually taken? Not normally important, but since we are discussing the very early dates of Indonesian photography; even a difference of four years is considerable.

Photo gravures

There were many photographs reproduced as photo gravures. Leo thought some were exceptional. Chronologically, that these are the large folios produced after the work of C.J. Kleingrothe; 6 items are represented in the collection. Dating from about 1895 to 1910, all were produced by J.B. Obernetter in Munchen. They are of very high quality.

From around 1915 Leo highlighted George P. Lewis’s 3 albums ‘Views of Netherlands India', ref. # 5324. The director of Photographic Atelier Kurkdjian & Co. in Surabaya, Lewis was one the most talented photographers in Indonesia at that time.

Not only that, he seems to also have been a real enthusiast, (witness the attention to detail in these 30 prints). In Leo’s view, this work was as good as looking at an original print. This may also be said of ref.# 5313, G. Krausse’s ‘Borneo’, a 3 set portfolio of 36 prints, some of great beauty.

It seems that more is known of Lambert & Co. photographers since well-known names such as Ernst, Feilberg, Kleingrothe, Salzwedel and Staphell, all worked for Lambert at one time or another. Leo recommended referencing the work by Falconer and Boom & Reed on this. Woodbury & Page did sometimes sign their photographs via a written name in the negative or by a (round) blind stamp from c. 1880.

Kurkdjian, to their credit, signed more of their work than most others. This was done by a rubber stamp or printed details on the reverse, and also by written and / or stamped details in the negative. Lambert & Co. mostly numbered their photographs, but also used a blind stamp later on. A catalogue of their stock photography was published in 1899, (photo copy in the reference library) listing a good number of their photos but by no means all. It may well be that commissioned work was not included in their sales catalogue.

There are still many Indonesian photographs of high quality which remain classified as ‘photographer unknown’.

Postcards, tourism literature, books and illustrated magazines have all contributed towards attributing photographs, as they sometimes credited the photo studio or photographer directly. The only known signed work by George Lewis is the three piece set ‘Views of Netherlands India’ ref. # 5324, making identification of many photographs by Lewis possible.

Postcards

As well as collecting original photographs, Leo also collected postcards depicting photographic images of Indonesia. Postcards are taking an increasingly more important role in the documenting of Indonesia’s visual history. Like films and illustrated magazines, postcards tended to be overlooked by researchers.

Being mechanically produced and reproduced, postcards are not individual artworks. Consequently they fall outside the scope of the acquisition policy of the National Gallery of Australia and art museums in general. Postcards are not only very close to original photography, they usually provide more information that can be found on the original photograph from which the card was made.

Sometimes (about15% of the time) they credit the photographer. Leo estimated that over 100,000 postcards were published in Indonesia up to 1940, 15% makes for a considerable contribution to the attribution of photographs. Since publishing a book on the subject of Indonesian postcards with Steven Wachlin, several researchers have availed themselves of the postcard collection.

Care needs to be taken not to use postcards to date the original photograph, as the same image was sometimes reproduced over a period of as long as 40 years.

What Leo did and did not collect and why

From the outset Leo collected things, including photographs, mainly out of concern that they may get lost over time. Indonesia was and still is a new country as far as its independent status goes. Photographs of the foregone era were not interesting to the Dutch, (as their colonies were something of the past), nor to Indonesians, where they were accorded low priority, as there were too many other things demanding their attention.

These two situations combined, created a kind of vacuum. While confining my time to the collecting of photographs and other relevant items, Leo’s interest did not extend to the technical specifications of the various photographic processes.

Restoration

From his work as an antiquarian book dealer, he became familiar with the restoration of old books and documents. To that effect, Leo enlisted a paper restorer who worked at one of the museums in Amsterdam. (It seems that several museums give tacit approval for these specialists to do some free-lance work as that will, at times, allow them to encounter difficult or unusual items to work on, enhancing their skills further).

Leo took some photographs in for restoration. On inspection of the prints, they were returned. The complex nature of the paper, (an almost non-existent fibrous type), made restoration work impossible for them to attempt. Besides, and crucially, the argument to refuse the job was also based on the complexity and variety of the chemicals used in the early printing processes of the photographs.

Leo then found a professional photo restorer, but sadly, one of his favourite photos was returned in a condition worse than it was previously. He never made use of photo restoration again. This was contrary to the situation with albums and folios, which the paper restorers / book binders had no problem in treating.

A final thanks from Leo Haks

Leo made a point of stating a special thanks go to Gael Newton, then Senior Curator of Photography, National Gallery of Australia. Gael first contacted Leo in 2006. Many emails followed with visits both ways. This included a meeting with Ron Radford, the Gallery's Director. “Gael, who conducted the negotiations, was a treat to work with, always amiable, despite her heavy workload. I learned much from Gael and will remain grateful to her for the knowledge she shared.”

And a thanks from Gael Newton to Leo Haks

It was my privilege to have conversed at length with Leo Haks while we were negotiating the purchase of his collection and in the years that followed including after he moved to New Zealand. As a curator for the national art gallery it was a fantastic experience and opportunity to engage with a private collector who was passionate and knowledgeable about photography.

So much of my research and subsequent exhibitions and publications on Indonesian photography were enhanced greatly from my association with Leo Haks. I remain indebted to his guidance and his generousity of spirit. He always there to offer advice and to share reseach. Thank you Leo, I miss the conversations we were still to have!

for more on Leo Haks and other useful links - click here

|