|

Table of Contents

Close-Up

Ohannes Kurkdjian’s duality

Vigen Galstyan (2014/2025)

|

#VG 1-1: Ohannes Kurkdjian Javanese ploughman c 1905 |

Ohannes Kurkdjian (1851–1903), founder of one of the most famous photographic firms in colonial Southeast Asia, was an itinerant Armenian who had arrived in Java in 1886 looking for a new life and fresh business opportunities. Born in Kyurin (now Gurun), an Armenian town in the Ottoman Empire, Kurkdjian moved to Tiflis in Georgia in 1870 after an apprenticeship in Europe.1

During the Russo-Turkish War of 1878–79, he was a photographer in the Russian Army, soon after which he relocated to Erivan (now Yerevan, Armenia). In this rural Armenian town, he could hope for little more than a bread-and-butter operation, but his ambitions extended beyond money making as his participation and awards in European photographic salons show.

He spent five months in 1879 photographing and studying the monuments of the ancient Armenian capital Ani and published Ruins of Armenia. Ani in 1881. Composed of forty stereoscopic views, this handsome album, purposefully printed in Armenian and French and not Russian, was an example of a local’s attempt to introduce his colonised people to their newly rediscovered heritage. It was part of a bigger project to resuscitate scholarly and national interest in Armenia’s patrimony.2

That these photographs coincided with the 1878–82 Armenian independence movement was no accident: Kurkdjian was active in this aborted endeavour and was subjected to political repression from the Tsarist government, leading to his escape to Vienna in 1881. Less clear is why he relocated to Southeast Asia, arriving first in Singapore in 1885, then Java in 1886. The existence of small but prosperous Armenian communities in both places and his adventurous nature and entrepreneurial zeal were likely reasons.

His Surabaya studio quickly prospered after opening in 1890. As well as studio portraiture, Kurkdjian also ventured into the vast Javanese archipelago, photographing villagers and workers in their immediate environment. Despite the impressive range in subject matter—landscapes, historic monuments, still lifes, ethnographic scenes, royal processions and industrial expansion—his Indonesian photographs adhered to and aided the positivist image of colonialism projected by the Dutch.

Kurkdjian’s enthusiastic collaboration with the Dutch government is further corroborated by the albums he presented to Queen Wilhelmina and by the Royal Warrant that she bestowed upon him in return in 1902. Nevertheless, the photographs that can be attributed to Kurkdjian himself are restrained affairs.

His large-format camera recorded intricately detailed observations of local people at work and at rest. The frisson of these photographs arises from the duality of the subjects’ representations as both subjugated and dignified, a quality also particular to Ottoman-Armenian photographic studios such as G Lekegian & Co and Abdullah Frérés. The theatricality, stiffness and compositional symmetry of these panoramic images hint at their ambiguous nature as recreations and masks, behind which lies a more unnerving reality.

|

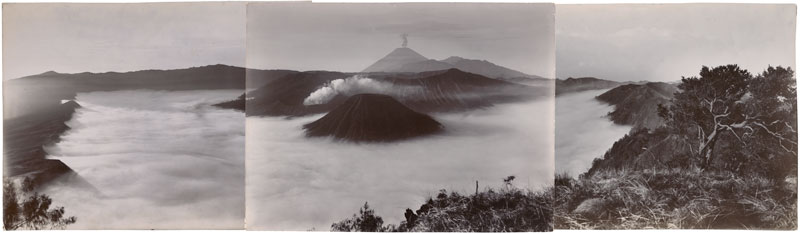

#VG 1-1: Ohannes Kurkdjian The sand-sea with Bromo and Semeru, Tengger mountains, East Java c 1900 |

Kurkdjian’s interest in asceticism and the sublime is evident in his images of Semeru and Bromo volcanoes in 1901. Barren and hyperreal, these photographs (see example, plate no 87) induce a sense of anxiety that transcends the armchair romanticism of nineteenth-century Orientalist landscape art. An exhibition of his photographs taken shortly after the Kloet eruption in May 1901 was praised in De Locomotief for bringing the viewer ‘into the wild world of grandeur, of feeling alone, of becoming a small person facing infinite creation’.3

As landscapes, they forgo topography to become exquisite studies of space. Such protomodernism would soon be replaced by the exoticism that the Kurkdjian brand would be associated with after his ‘sudden death’ in 1903.4

The studio was taken over by Englishman George Lewis, whose practice developed the local strand of Pictorialist photography. By the time the studio shut down in 1936, O Kurkdjian & Co had had a profound impact on how the Dutch East Indies was perceived by the West as well as on later developments in Indonesian photography.5 While ultimately propagating the colonial agenda, O Kurkdjian & Co’s overall output remains a complex picture of a region undergoing tumultuous transitions.

Footnotes:

- See Robert Pashayan, Aram ev Artashes Vruyrner, Hayastan, Yerevan, 1989, pp 15–20.

- In 1880, Kurkdjian had already collated a photographic album of monuments in Western Armenia, which he presented to the noted historian Kerovbe Patkanian.

- ‘Fotogratleen van de Kloet’, review, in De Locomotief, no 50, 17 August 1901, p 187, translation by Mark Hillis.

- Although the year in which Kurkdjian died has been contested, his death by an unknown cause in a hospital in Surabaya on 12 June 1903 was, in fact, reported in Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad, 15 June 1903, p 3.

- Janneke van Dijk and others, Photographs of the Netherlands East Indies at the Tropenmuseum, KIT Publishers, Amsterdam, 2012.

Return to Introduction and the Table of Contents

|