|

Table of Contents

Close-ups

Kassian Cephas, a self-made man

Matt Cox (2014/ 2025)

|

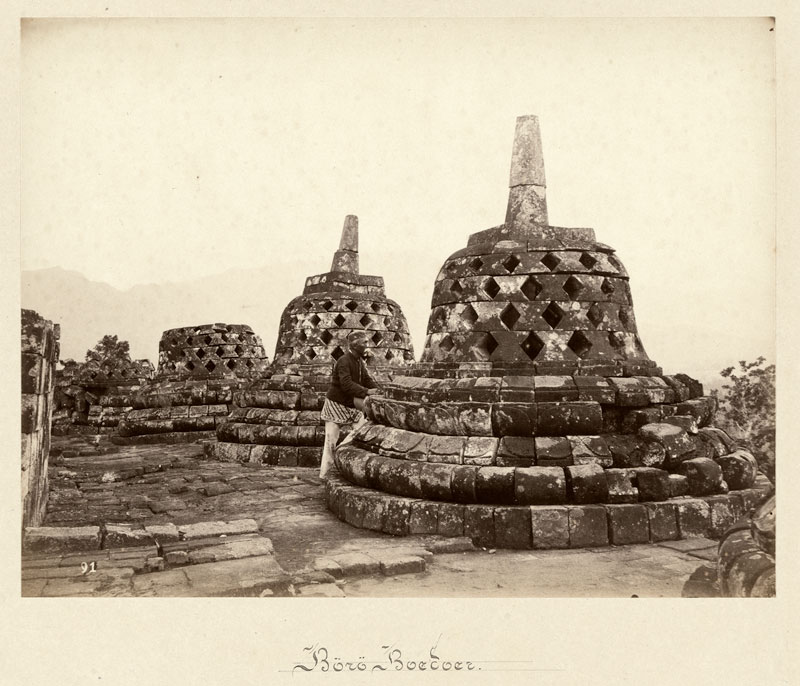

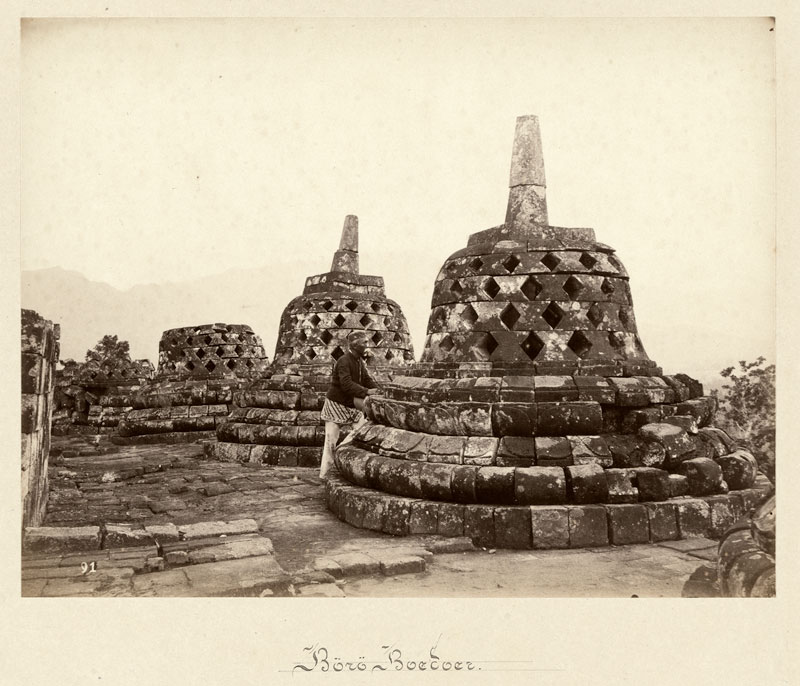

#MC 1-1: Kassian Céphas Borobudur c 1890 |

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, European ideas of the self were informed by a prevailing tension between the competing virtues of Romantic and Positivist thought. These ideas had profound resonance in colonial Java, particularly among the emerging community of Javanese intellectuals and artists who forged their own existence in the space between tradition and modernity.

Indonesia’s first women’s rights activist Raden Ajeng Kartini (and many others) imagined the change of century as the dawning of a new era and the awakening of a people in slumber. On 1 February 1903, she wrote to Jacques Henrij Abendanon, the Minister of Culture, Religion and Crafts in the Dutch East Indies, to express her desire to preserve Javanese culture in a way that would ‘give outsiders a true picture of us Javanese’.1

She wrote: ‘I wish so often that I had a photographic apparatus and could make a permanent record of some of the curious things that I see among our people’.2

Although there is little record of indigenous photographic studios registered for business at the turn of the twentieth century, the studio of Kassian Céphas (1845–1912) and his three sons, Sem, Fares and Jozef, received widespread public attention. Céphas’s desire to support himself and his family though commercial activity was realised in the opening of his Yogyakarta studio in 1872, which afforded him independence from aristocratic and Dutch government patronage.3

In a society divided along ethnic lines since 1854, Céphas’s assimilation into the European middle class is indicative of his ability to forge an identity as a modern self-made man in the space between the colonial project and the Javanese courts.4

Céphas’s mobility between the two sometimes Kassian Céphas Borobudur c 1890 conflicting spheres and his ability to disengage and reconnect himself to both the Javanese and European communities differentiated him and enabled him to form an identity in affirmation of self rather than in opposition to the other.5

Céphas championed the theatricality of the photographic reproduction in his intercourse with colonial policy and used it to describe his own transition from colonial subject to modern Javanese businessman empowered by the technology of the camera. |

|

|

#MC 1-2: Kassian Céphas Young Javanese woman c 1885 |

|

In colonial Java, photography was used to articulate the ambiguous dialectic of old and new, colonial and vernacular. Old was represented by Javanese tradition exemplified by court ceremony and archaeological sites. New was represented by Dutch enterprise illustrated with pictures of industry, machine manufacturing and agricultural projects. Céphas traversed the two, old and new, fluidly.

Céphas’s photographs respond to the ambiguity of his position and of the more general societal changes by at once providing a Javanese presence of order and calm within a period of dramatic economic and social change and expressing the altered perception of the Javanese aristocratic function that gave rise to the Indonesian individual.

The emasculation of the Javanese priyayi (aristocracy) due to colonial pressures coincided with opportunities for non-priyayi in the areas of business, politics and education.6 The rise of the non-priyayi in public life via press media provided them a new means for self-identification and self-reflection, which afforded them a distance from both the colonial regime and their puppet aristocracy.

Céphas, who lived in and operated his studio on Loji Kecil in a predominantly European residential area, was precisely one of those individuals who formed the membership of an emerging middle class who recognised status based on successful commercial enterprise.7

Céphas produced portraits for both Javanese and European clientele. He also created the first Indonesian photographic self‑portrait to be widely published, although it was quite modestly disguised as a documentary photograph of an archaeological site.

In his 164 photographs of Borobudur, taken between 1890 and 1891 for the Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies, Céphas introduces himself to his international audience: the photographs numbered from 86 to 89 include a lonely and likeable modest figure of an elderly man with a proud moustache seated among the architectural monumentality of Borobudur. He seems to caress the stone work rather than stand upon it and is depicted as being in simpatico with his architectural surrounds, especially when compared to the usual bravado embodied by European archaeologists standing defiantly on the highest peak.

One photograph shows Céphas laying his hands tenderly on an ancient Buddhist stupa at Borobudur. Céphas’s photographs of Indonesia’s monuments that were either being studied or undergoing restoration at the turn of the century present him as a man aware of his own agency and capacity to effect change; in other words, a modern man.

These theatrical self-portraits are composed and arranged in a way that simultaneously expresses a critique of the assumed objectivity of the archaeological project and inserts his own persona into the history of Dutch-Indonesian relations.

|

#MC 1-3: Kassian Céphas Three women creating batik fabric c 1880 |

| |

|

#MC 1-4: Kassian Céphas Four male court dancers c 1880–1905 |

Footnotes:

- Raden Ajeng Kartini, letter to JH Abendanon, 1 February 1903, in Hildred Geertz, Letters of a Javanese princess, University Press of America, Lanham and London, & The Asia Society, New York, 1985 (1964), p 215.

- Kartini, letter to Abendanon, in Hildred Geertz, Letters of a Javanese princess, 1985 (1964), p 215.

- Prior to 1872, Céphas had been working for the sultan for a number of years, at least in the capacity of apprentice.

- As part of this claim to modernity and individuality, Céphas pursued equal legal status with the Europeans. His success was confirmed in print in the Statsblad, no 221, 1891, when he and his two sons were granted European legal status.

- Claude Guillot, ‘Un exemple d’assimilation a Java: le photographe Kassian Céphas (1844–1912)’, Archipel, vol 22, no 1, 1982, p55–73.

- Suzanne A Brenner, ‘Competing hierarchies: Javanese merchants and the priyayi elite in Solo, Central Java’, Indonesia, vol 52, October 1991, p 66.

- It was widely understood that the pursuit of wealth was inappropriate and degrading for members of the Javanese aristocracy.

Return to Introduction and the Table of Contents

|