|

Table of Contents

IN FOCUS

Colonial machine: the image of industry

Alexander Supartono

(2014/2025)

|

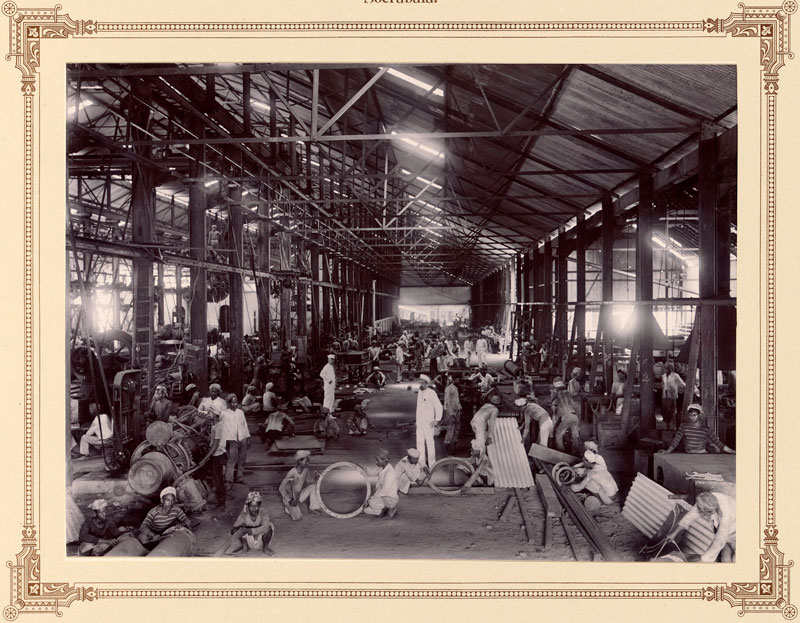

| # AS 4-01: George Lewis Foundry with furnaces towards east west in De Nederlandsch‑Indische industrie 1902 |

The upper part of a giant tyre-rolling mill is suspended in the middle of the factory foundry; the other half is still lying down on the floor with more than a dozen people around it. The floor is unplastered and the workers are barefoot and wearing traditional Javanese batik head cloths. The Dutch supervisor is wearing an all-white outfit, the quintessential European attire in the tropics to keep cool in the heat. He poses against an iron pillar and stares back at the camera.

Similarly, the Javanese workers are not in postures that would indicate an active factory scene: most are squatting, some are standing; they are idly touching the half tyre‑rolling mill on the ground or holding pieces of metal, tools or the dangling iron chains. Their heads are pointing to the floor and only two nervously glance at the camera.

The giant tyre-rolling mill would be the dominant feature of mill houses for the 178 sugar factories that operated in Java by the turn of the twentieth century. This 1902 photograph is from the album De Nederlandsch-Indische industrie, named after the metal manufacture company that was founded in 1878 and responsible for the construction of modern transportation infrastructure and other public works in the Dutch East Indies.1

The photograph depicts the foundry, the most important part in metal manufacture, where tons of bulk metal was cast into shapes. Work safety was an absolute requirement in the foundry. Mistakes had fatal consequences. Precision had to be navigated between physical strength and physical control, where, as the photograph suggests, workers moved extremely heavy and hot metal parts with manual cranes, or even bare hands.

But, in the photograph in question, there is no action. Everybody purposefully paused and the Dutch supervisor performed an apathetic pose. The hanging half tyre-rolling mill is the only indication that work had taken place and would continue after the photograph was taken.

|

| #AS 4-02: O Kurkdjian & Co De Nederlandsch-Indische industrie 1902 |

| |

|

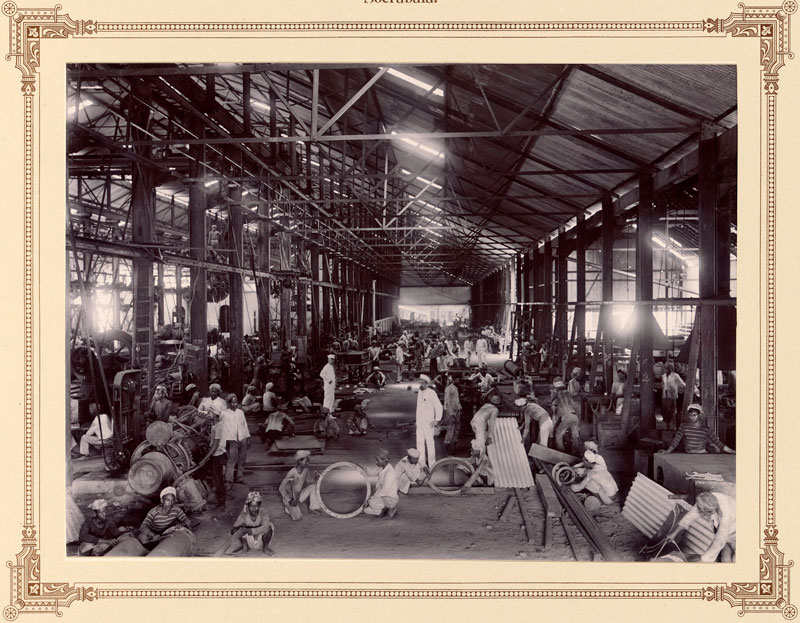

| #AS 4-03: George Lewis Sheet-metal workshop and right forge seen from west-east in De Nederlandsch-Indische industrie 1902 |

The album, with a figure resembling Hephaestus (the Greek god of smiths and industry) on the cover, consists of twenty-one pages and is comprehensive of the kind of visual records that would be equivalent to a company profile album today. It was a common practice for industrial enterprises to commission company albums as a token of their success and riches in the colony as well as for purposes of posterity. This practice provided a socioeconomic basis for the interrelationship between the rapid development of a market for commercial imagery and the colony’s industrialisation.2

However, the working scenes in this album did not follow the thematic and aesthetic glorification of man and machine photographs common in Europe.3 The scenes were orchestrated and sitters were under the photographer’s direction, but the pictures were not particularly tidy; workers are scattered in the space and those that pose as if working are unconvincing.

Although the photographs capture the entire scene, they do not suggest exemplary depictions of unique technological advancements in metal manufacture. Most of the production process took place on the factory floor and relied heavily on manual work. There is a noticeable absence of enticing geometric patterns that would indicate the complex technology and structure of machinery. Perhaps, this is the point; they are manufacturing components for modern and complicated machines rather than operating them.

The photograph on the previous page certainly manifests such an intention, and the monumental size of the suspended half tyre‑rolling mill is an obvious choice to impress viewers (particularly as there are two other photographs of the suspended tyre-rolling mill in the album). With ambient light coming in from the ceiling windows and reflected on the factory’s walls, the photographer used a slow shutter speed to achieve maximum depth of field and sharpness. This allows for close inspection of the different machine components being made and of the number of local workers in the photograph, which reveals four more on the top operating cranes—other photographs in the album include even more local workers partly concealed behind machine parts.

Early machine photographs in the Dutch East Indies rarely showed the actual industrial process—machines were mostly depicted idle.4 This was also the case with depictions of sugar factories. Workers and supervisors in the re-enactments of working scenes were extremely rare due to the technical limitations of photographic material and equipment at the time—the long exposure times that were required meant people had to remain completely still to register clearly in a photograph. These early technical restrictions, however, developed particular characteristics of factory-interior photographs in the Dutch East Indies, where their idiomatic nature as quasi-documents of the colonial industry was to celebrate the success of the colony’s industrialisation.

Such a celebration had turned the factory’s interior into a photographic studio in which the machine became either the backdrop for portraits of proud industrialists or was fetishised as an artistically crafted object. The first type mostly exists in the family albums of industrialists in which the factory interior views were seen as part of the family chronicle, hence the necessity to present people in the photograph whose names were usually identified in accompanying captions.

The second type more commonly features in formal company photo albums. In both cases, the photographer usually had the factory cleared from all working activities, which explains the frequent absence of local workers. While De Nederlandsch-Indische industrie includes two photographs of the second type, it also offers different insights into the industrial image of the Dutch East Indies. First, the enterprise was a machine-making factory but there are no photographs of machinery, which means either machinery had not yet been installed (so that it could be utilised as a portrait backdrop) or machine components were not yet assembled into attractive objects.

Second, the factory floor is not clear, as one would expect; instead, the actual details of the machine-making process is on display, albeit with some element of posing. Third, the depiction of local workers performing work that required knowledge and training to build, for instance a tyre‑rolling mill, was a rarity when technology was the very site of the Dutch to exercise their domination.

By presenting skilled Javanese workers with their Dutch supervisors, it illustrated how race relations worked on the factory floor, where the organisation of work made the social and race hierarchies less visible; class and capitalism had prevailed and moderated racial difference in the course of the colonialism.

- See George Lewis’s De Nederlandsch-Indische industrie 1902 at KITLV digital media library, <media-kitlv.nl>.

- Steven Wachlin, ‘Commercial photographers and photographic studios in the Netherlands East Indies 1850–1940: a survey’, in A Groeneveld and others (eds), Toekang potret: 100 jaar fotografie in Nederlands Indie 1839–1939, Fragment Uitgeverij, Amsterdam, & Museum voor Volkenkunde, Rotterdam, 1989, pp 177–92. Wachlin’s mapping of 540 commercial photography studios in seventy-seven cities and towns in the Dutch East Indies between 1850 and 1940 suggests a geographical interconnection between the industrial centres and the blossoming of commercial studios around them.

- For examples, see the machine photographs in Exhibition of the works of industry of all nations 1851: reports by the juries on the subjects in the thirty classes into which the exhibition was divided, Spicer Brothers, London, 1852; and the indoor factory photographs of well-known German steel company Krupp in Klaus Tenfelde (ed), Picture of Krupp: photography and history in the Industrial Age, Phillip Wilson Publishers, Munchen, 1994.

- This assessment is based on the observation of more than fifty sugar factory albums produced between 1880s and 1920s in Java in the collections of Tropenmuseum and Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and KITLV in Leiden.

Return to Introduction and the Table of Contents

|