|

Table of Contents

IN FOCUS

Personal albums from early 20th century Indonesia

Susie Protschky (2024/ 2025)

|

| 00-05: Three generations posing with photographs and flowers c 1935–41, in an Indo-European family album |

| |

|

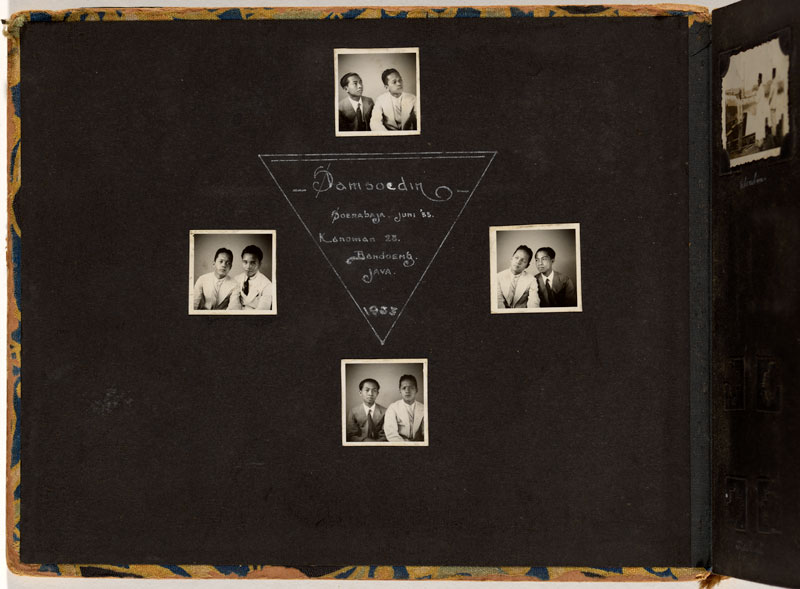

| #SP 3-01: Samsoedin family album c 1933 |

Personal albums have only recently begun to attract scholarly attention for the alternative views of photography’s history they enable, especially insofar as they reveal how amateur practitioners created and collected vernacular styles of photography that were not beholden to the values of high art.

For the greater part of a century, up until the recent digital revolution, which has begun to change the way we take, store and share personal photographs. the tactile book-like album filled with glued-in hand-annotated snapshots was the most widespread and intimate record that ordinary people the world over left of themselves to posterity. Seen through the eyes of social and cultural historians, the shift of photography out of the studios of professionals and into the hands of amateurs in the late nineteenth century created new opportunities for a variety of social groups to amass personal archives and produce visual reflections on the times in which they lived.

|

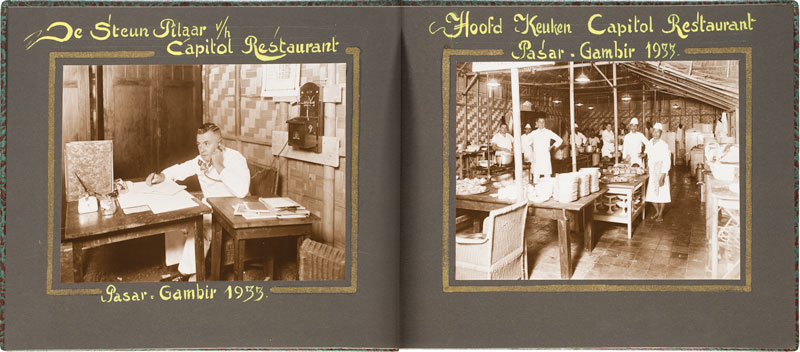

| #SP 3-03: Jan Grader presentation album 1933 |

Work and leisure in Dutch East Indies personal albums

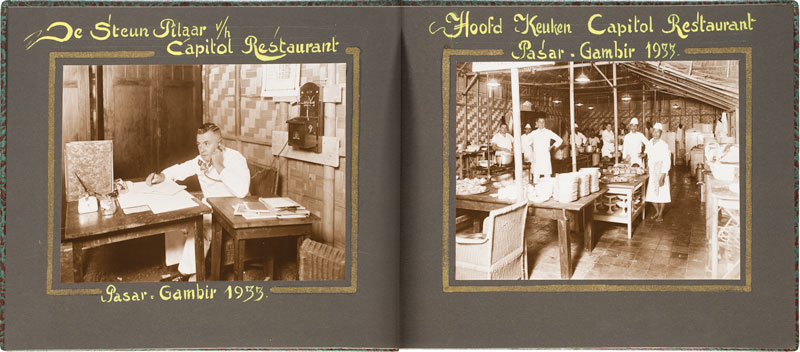

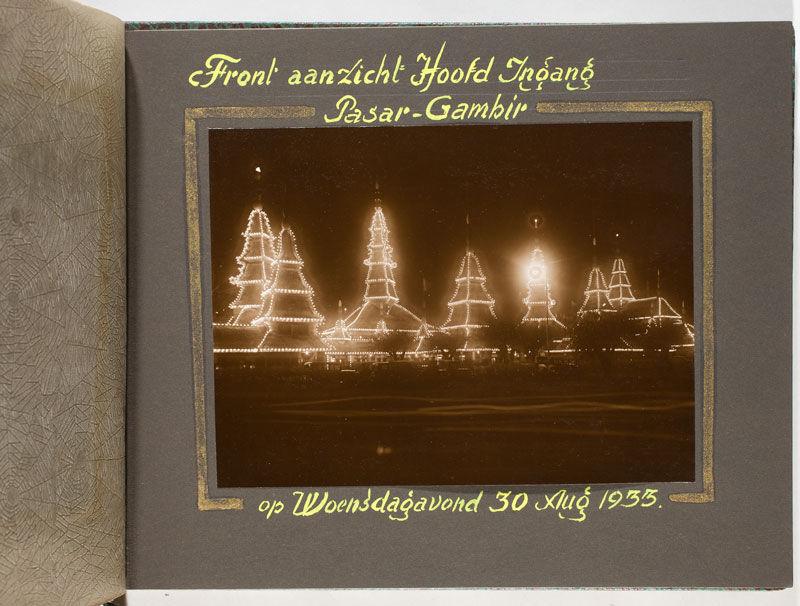

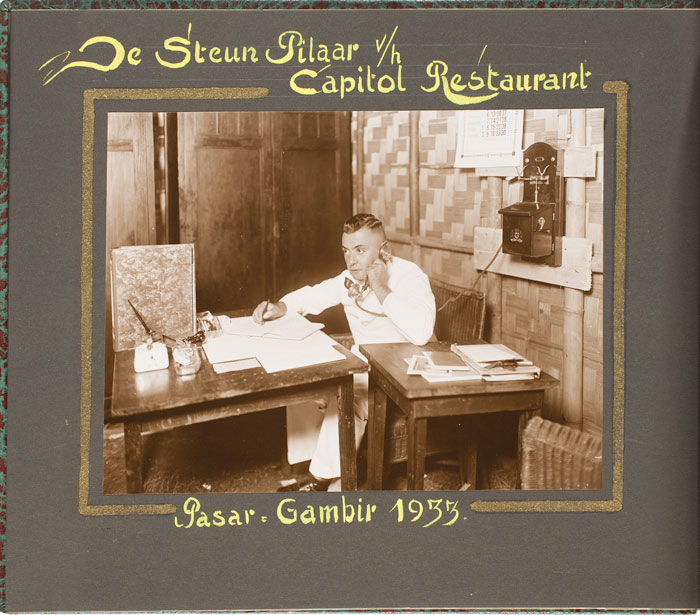

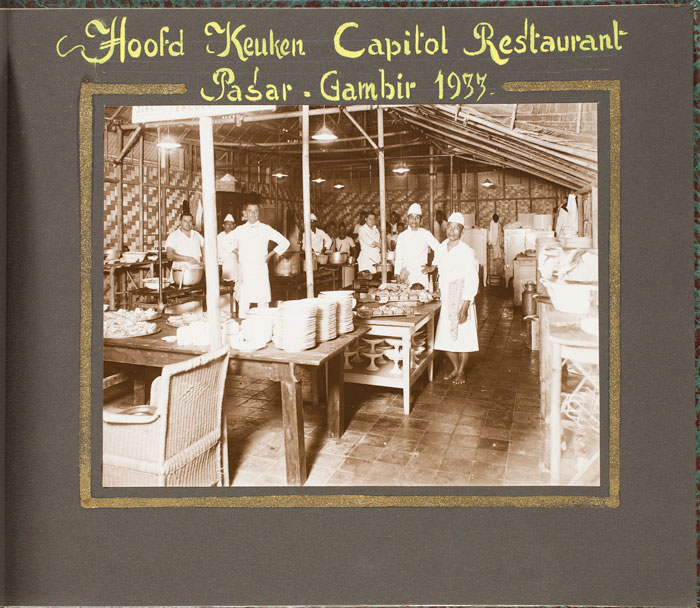

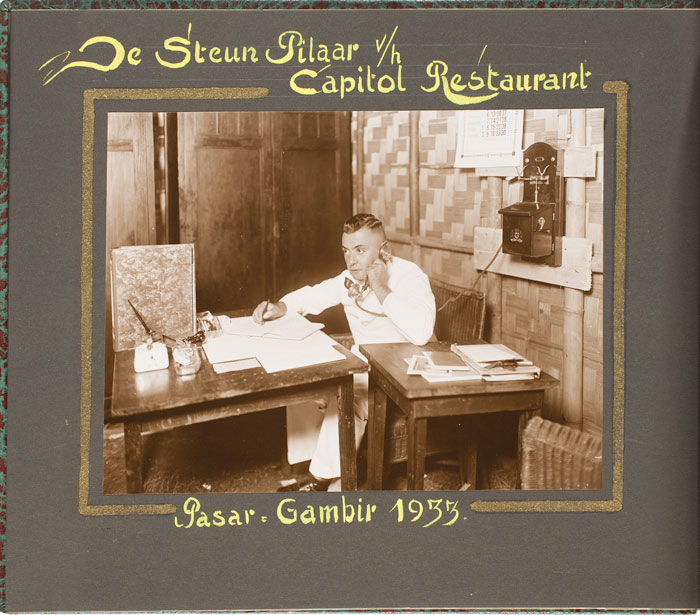

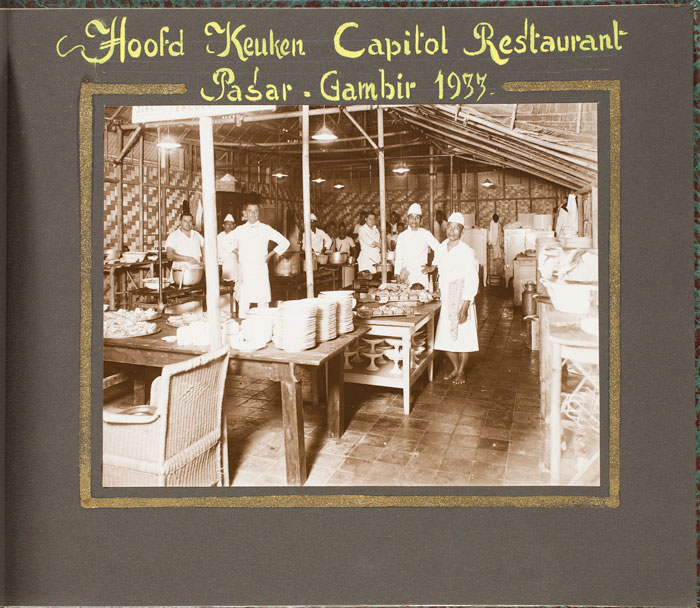

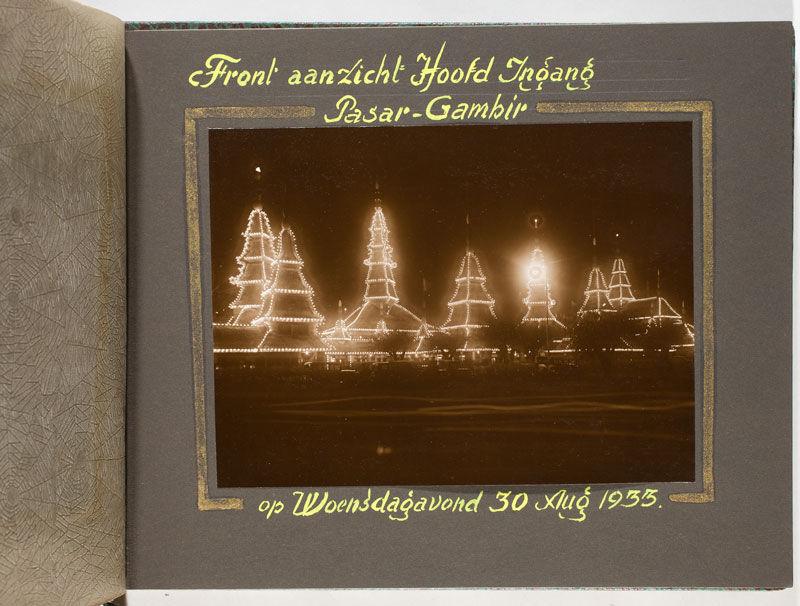

‘Personal’ albums in the early twentieth century did not exclusively consist of ‘family’ photographs; not at least in the narrow sense that is presently conventional. Corporate albums, gifts given by workers at a firm or factory to a (usually more senior) colleague often to observe his or her departure, were also popular. A fine example in this genre is the album created in 1933 that showed Pasar Gambir, the famous market held annually in Batavia (now Jakarta) to celebrate the Dutch queen’s birthday (koninginnedag).

The hand-painted dedication on the opening page of the album reveals it to have been a gift to Jan Grader, probably from his coworkers. It appears Grader was manager of the Capitol Restaurant, an establishment for more illustrious visitors to the market. A portrait showing him in his office, posing with good-humoured exaggeration as the hardworking ‘support pillar’ (steun pilaar) of the restaurant, is interleaved between striking examples of night photography that make the most of the dazzling electric lights festooning the market buildings, as well as snapshots of Grader’s team of Javanese and European staff labouring in the Capitol’s kitchens and cellars.

|

| #SP 3-04 & 3-05: Jan Grader presentation album 1933 |

At first glance, a second album in the National Gallery collection also appears to be a corporate album belonging to another manager, but closer inspection reveals it to straddle the two genres of work and family photography. The album dates from the period 1915–20, and seems to have belonged to the European manager of Modjo-Agoeng, a major sugar estate to the west of Surabaya (East Java).

The firm was established in the 1880s by a private Dutch entrepreneur and was acquired in the 1920s by the powerful Dutch Trading Company (NHM, Nederlandsche Handel-Maatschappij).1

Most of the album’s pages are filled with photographs of the processes involved in growing and processing sugar, from the field to the factory floor. The first pages, however, show the well-appointed private house and grounds of the manager and a little girl who was probably his daughter. One page combines a photograph of the manager standing at the entrance to his office (kantoor) with snapshots of interiors from the residence: one of the kitchen, the other of the child posing (together with a favourite doll) in her elegant little nursery.

The Modjo-Agoeng album lucidly illustrates a common feature of personal albums from early twentieth-century Indonesia, namely that the separation between public and working and private and family lives and by extension corporate and family photography was not then as distinct as it has become in vernacular photographic practice today.

For European factory managers, office workers and colonial administrators, the bureau was often contiguous with the home, and the daily rhythms of life were not entirely dictated by industrial time. Work and family spheres also overlapped in the households of the professional elite in other ways.

A vast number of personal albums produced by well-to-do Europeans and Indo-Europeans (people of mixed descent) reflect the widespread reliance on indigenous servants among this class. The National Gallery collection is representative in this regard, as illustrated by a typical album belonging to an unknown European family comprising a mother, father and their two small boys.

Viewed from the perspective of the family, particularly the children, the Javanese houseboy (jongos) and especially the nanny (babu) who feature so often in such albums evoke fond feelings of intimate domestic life. However former servants recollecting the same scenes in the present day often remember their housekeeping and childcare duties more narrowly as work, and their relationship to the adults in the household as one between employers and employees.2

Lifestyles of the well-to-do

Family albums from colonial Indonesia frequently provide glimpses into the comfortable lives of those who could afford to pursue amateur photography, a hobby that remained relatively expensive in the early twentieth century, even if it required less skill and capital than it had in the previous century.

The vast majority of albums now in public institutions, including the National Gallery, suggest that it was mainly Europeans, Indo-Europeans, Javanese nobility and prosperous Chinese, the elite in Dutch East Indies society, who could afford to take photographs for their own pleasure. Where many historians often focus (quite aptly) on the legal, cultural, political and economic inequalities between these groups, family photograph albums reveal some of the intriguing similarities between them and, as such, provide special insights into the social history of traditional as well as emerging ruling classes in early twentieth-century Indonesia.

|

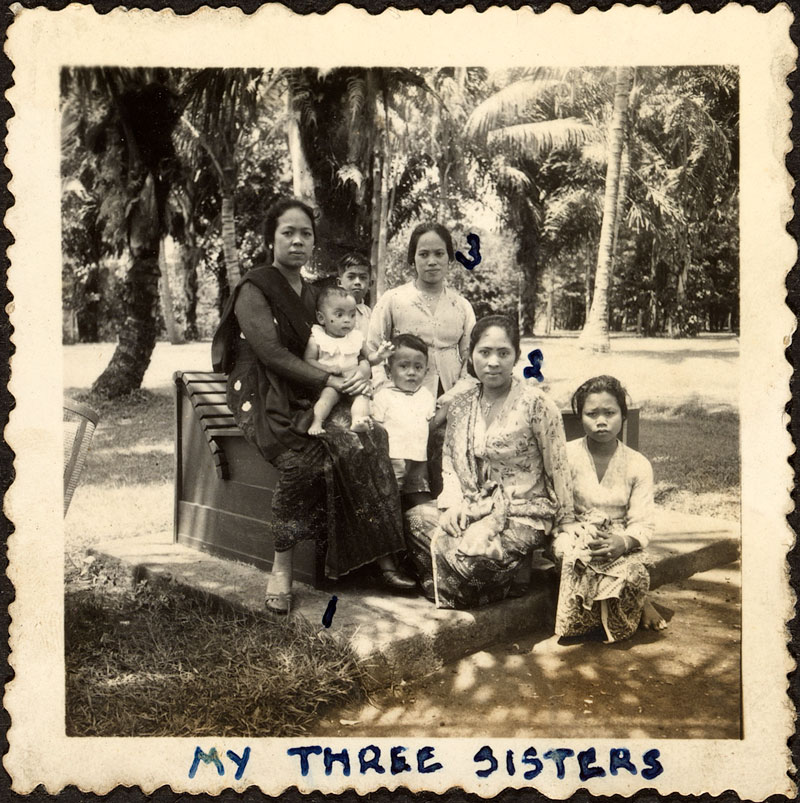

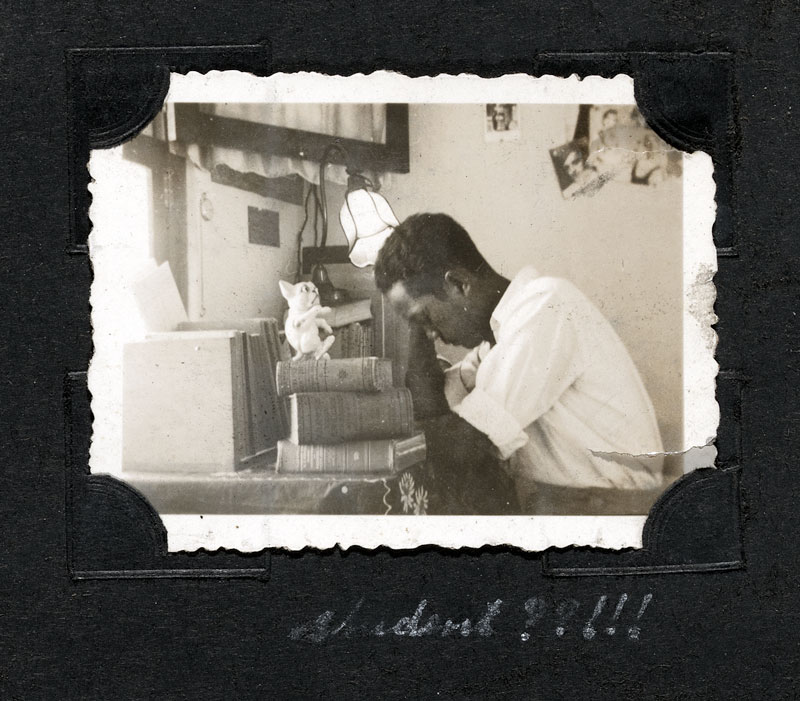

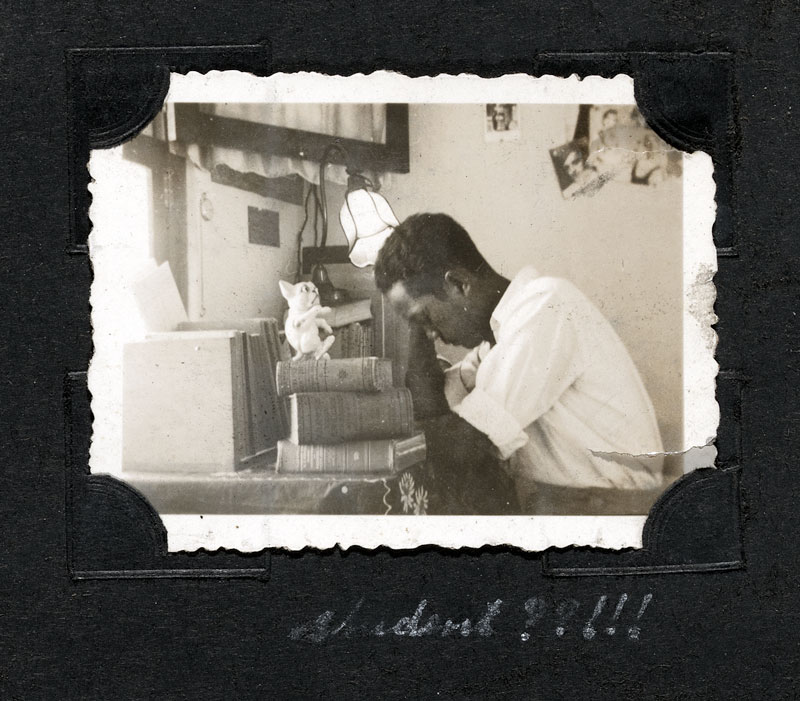

| #SP 3-06, 3-07 & 3-08: My three sisters, Student??!!! and My ‘sister’ in the Samsoedin family album c 1933 |

|

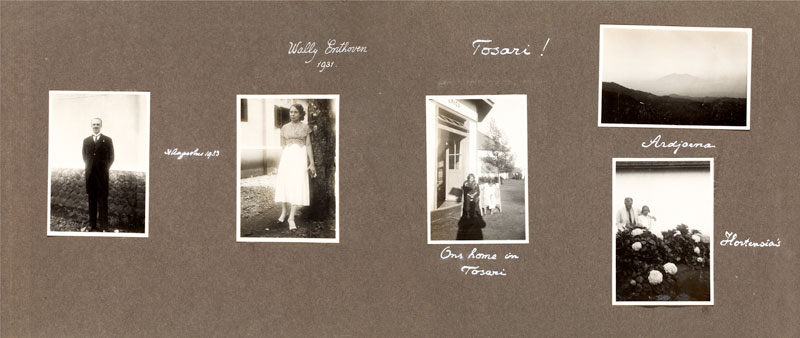

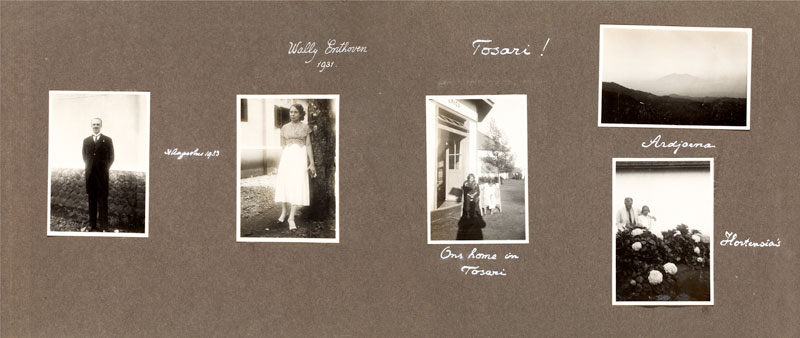

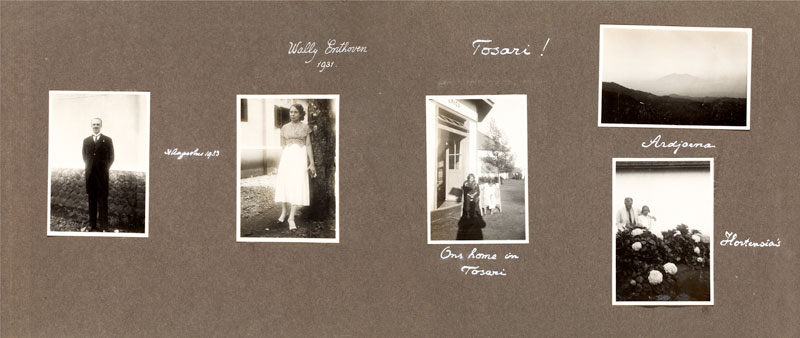

| #SP 3-09: Wally Enthoven album c 1931–34 |

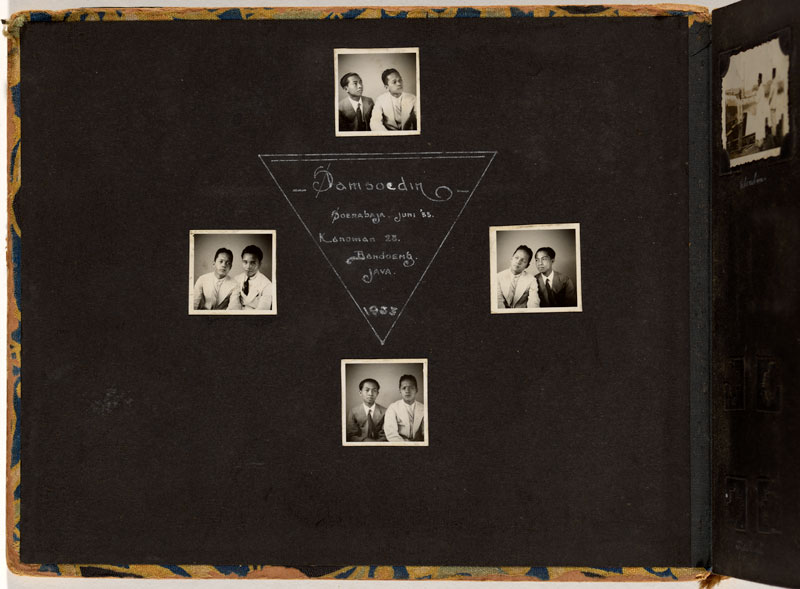

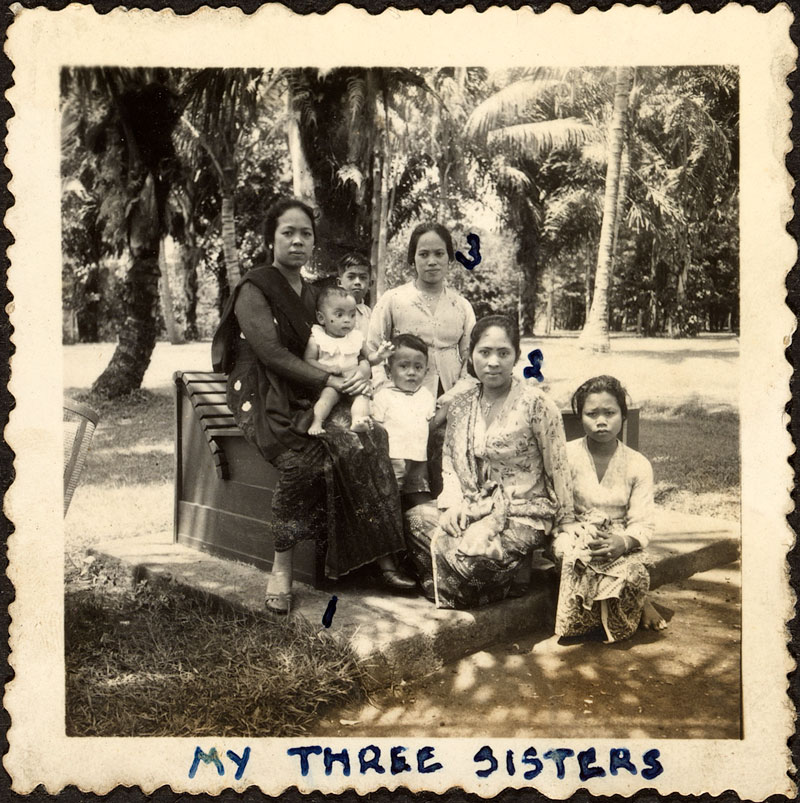

This is illustrated by three particularly fine albums in the National Gallery collection, all made in the 1930s. The first belonged to an affluent Western-educated and possibly aristocratic Javanese family by the name of Samsoedin. While studio portraits of Javanese from this class proliferate in archives, amateur family albums are rare. This example is noteworthy for giving visual form to the complex social world such families inhabited in the early twentieth century, one that combined aspects of elite Javanese culture with middle-class European lifestyles.3

The former is evident in this album in several studio portraits of men and women wearing the traditional costume of aristocrats, and in the references to polygamy, being a common feature of elite Muslim households, contained in several captions that identify the album maker’s ‘sisters’ (sister wives). Although difficult to confirm, it remains an intriguing possibility that the album was assembled by the fourth wife not pictured.

The captions throughout in English, Dutch, Malay and Javanese reveal the level of education that members of this family clearly received. The photograph of the diligent student with his head in the books shows some of this process in action. Indo-European families made the other two albums.

Given that the vast majority of people with legal European status in the Dutch East Indies were in fact born in Indonesia and sometimes also had Asian relatives, albums made by Indo-Europeans represent an important social group.4

The first example belonged to Wally Enthoven, the daughter of an Indo-European mother (known only as ‘moes’, or ‘mum’, in all the captions) and Karel Lodewijk Jan Enthoven, a senior Dutch official, expert on customary law (adat) and Director of Justice in the Dutch East Indies. The unknown family pictured in the third album were typical of less eminent Indo-Europeans. The family consisted of a Dutchman serving in the colonial military and his Indo-European wife, together with their extended, ethnically mixed relatives, including a couple of Asian matriarchs.

One trait all three albums share, regardless of their makers’ ethnicity, is a focus on the comfortable lifestyles and pleasant times the families at their centre seem to enjoy together. This trait reflects the existence of a multi-ethnic elite who shared certain notions of respectable domesticity in early twentieth century Indonesia and the growing importance of family photography in the self-representations of this class.

The albums all show for example stylish home interiors, sometimes with the latest consumption goods on display such as sewing machines.5

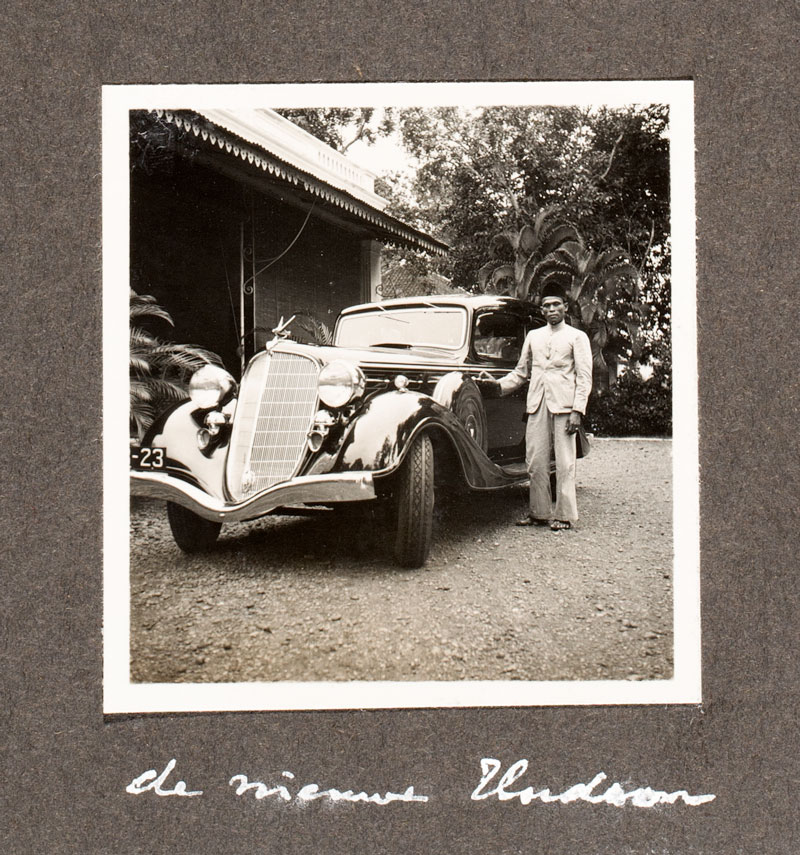

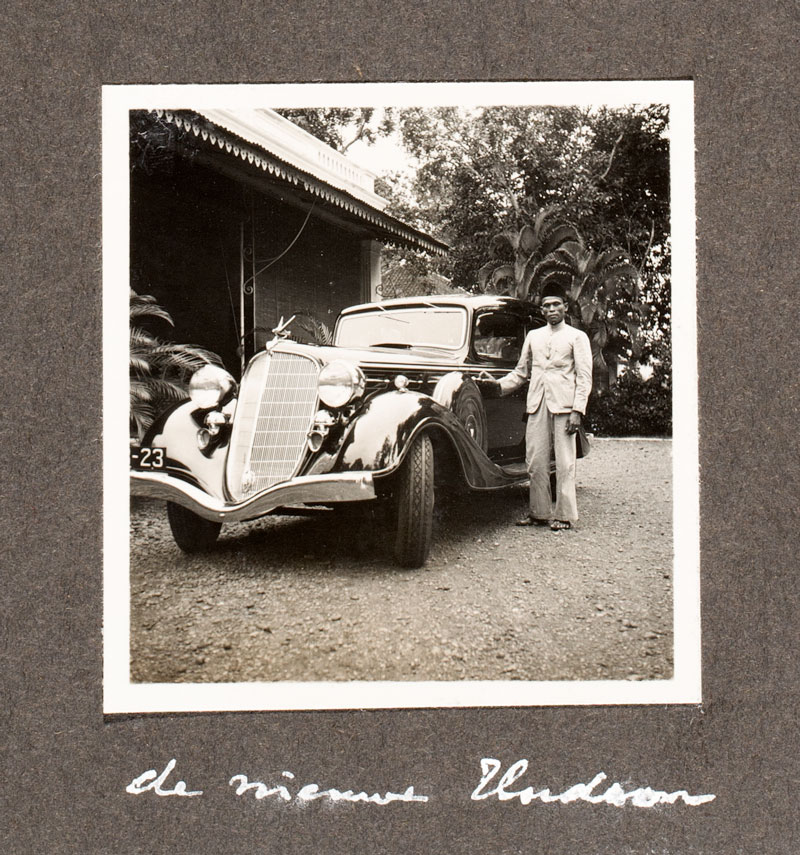

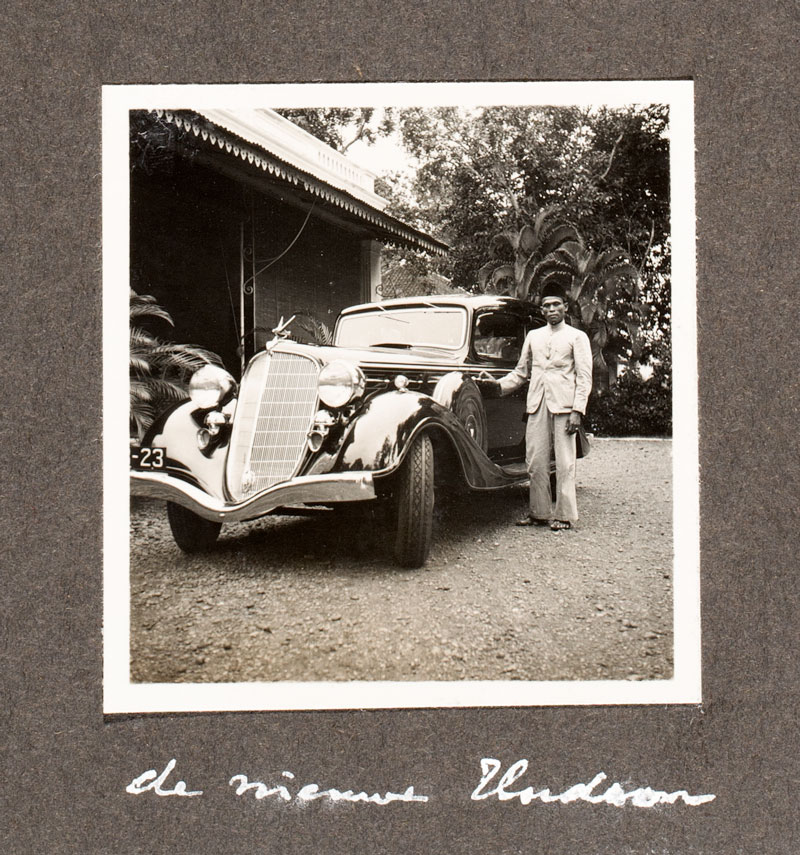

Each family saw fit to photograph its most expensive status symbol, the car, in ways that communicate the social distinctions within the elite from the privileged Enthovens, with their shiny Hudson attended by its chauffeur to the more quotidian utility vehicle of the unknown middle-class family. In the Samsoedin’s album photographs of the car are combined on a page showing other modes of motorised transport such as buses and trains.

|

|

|

#SP 3-10: The new Hudson

in the Wally Enthoven album c1931–34 |

|

#SP 3-011: Couple posing before their utility vehicle

in an Indo-European family album |

All three albums show the families vacationing at mountain resorts. Tours of Central Java’s Hindu-Buddhist antiquities were also popular. The Javanese family even journeyed to Bali, a destination that is strongly represented in other personal albums as well as art photographs in the National Gallery collection. Bali gained international attention in the early twentieth century for the variant of Hinduism that informed the religious ceremonies, arts and theatre of the island.6

The unknown Indo‑European family visited relatives in Europe, another destination that is often pictured in personal albums from the period. Photographs of an Asian man abroad subvert the orthodox narrative of Europeans monopolising the privilege of travel in a colonial world and provide visual evidence of the ‘colonial migration circuit’ between Europe and Indonesia that was one of the defining experiences of the multi-ethnic Indies elite.7

Uniting scattered families in a colonial world

Such images also illustrate an important social function of family photographs in late colonial Indonesia. Family photographs are defined not just by their content, but also by what is done with them, whom they are shared with, how and to what purpose. When such images are looked at together by family members, or mailed to relatives who live far away, albums of personal photographs not only represent family, they constitute it.8

Early twentieth-century family photography introduced a new form for uniting scattered families in a colonial world. It brought people together in recollection over the pages of an album and visually reunited family members who were separated by space or divided by time, as in the case of descendants looking back on deceased relatives. The material quality of both photographs and albums,being their status as tactile objects, enabled these practices as it made images portable, able to be printed, copied and reused in different venues, and the images could be elaborated by texts such as letters and annotations.9

The miscellanies at the back of the anonymous Indo-European album illustrate some of the typical social functions of family photography. One image shows three generations of the clan together, seated among flowers and various portraits of relatives who may have passed away or lived in other places. As Australian art historian Geoffrey Batchen has perceptively noted, photographs of photographs visually reunite separated family members and commemorate the act of relatives being remembered.10

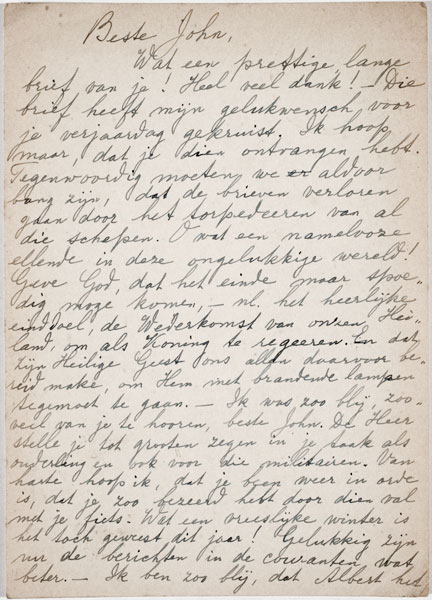

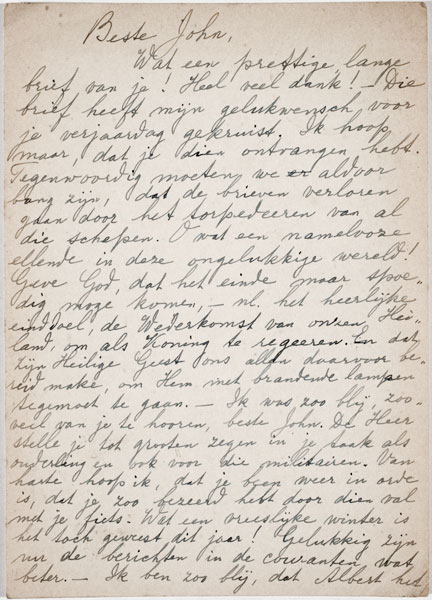

The sitters in these portraits are looking into the eyes of several audiences – in the present it is their own and those of absent relations; in the future it is those of their descendants. The same bundle of loose items in this album includes a common textual partner to the family photograph, the letter.

‘Dear John’, it begins in Dutch and then meanders over the commonplaces of correspondence in the age of mail by steamship: thanks for the last epistle received (a long one), fears that such letters will be lost in transit. Complaints of a freezing winter suggest the letter came from a relative in the Netherlands, and wishes that God might soon return to reign as king on earth show that the writer was a pious Christian.

Such letters remind us that these albums have made a further journey, beyond the trip to their intended private ‘home’ where a viewer knew and could name all the subjects in the photographs.

The story of how each of these albums became separated from their families and part of the National Gallery collection is, on the individual level, often irretrievable. However, at the collective level the albums are part of a larger story of war, revolution, migration and decolonisation in the 1930s and 1940s that gave rise to the Republic of Indonesia and that replaced the social elite we see in many of these albums with a different ruling class.11

- G Roger Knight, Commodities and colonialism: the story of big sugar in Indonesia, 1880–1942, Brill, Leiden & Boston, 2013, pp 192, 194.

- Ann Laura Stoler & Karen Strassler, ‘Memory-work in Java: a cautionary tale’, in AL Stoler, Carnal knowledge and imperial power: race and the intimate in colonial rule, University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles & London, 2002, pp 162–204.

- Susie Protschky, ‘Tea cups, cameras and family life: picturing domesticity in elite European and Javanese family photographs from the Netherlands Indies, c 1900–1942’, History of Photography, vol 36, no 1, 2012, pp 61–2.

- Ulbe Bosma and Remco Raben, Being ‘Dutch’ in the Indies: a history of creolisation and empire, 1500–1920, trans W Shaffer, Research in International Studies Southeast Asia Series, no 116, Ohio University Press, Athens (Ohio), 2008, p xvi.

- Jean Gelman Taylor, ‘The sewing-machine in colonial-era photographs: a record from Dutch Indonesia’, Modern Asian Studies, vol 46, no 1, 2012, pp 71–95.

- Adrian Vickers, Bali: A paradise created, Periplus, Singapore, 1996.

- Harry A Poeze, In het land van de overheerser: Indonesiers in Nederland 1600—1950, Foris, Dordrecht, 1986; Ulbe Bosma, Indiegangers: Verhalen van Nederlanders die naar Indie trokken, Bert Bakker, Amsterdam, 2010.

- Gillian Rose, Doing family photography: the domestic, the public and the politics of sentiment, Ashgate, Surrey, 2010.

- Elizabeth Edwards and Janice Hart, ‘Introduction: photographs as objects’, in E Edwards and J Hart (eds), Photographs, objects, histories, on the materiality of images, Routledge, London & New York, 2004, p 1–15.

- Geoffrey Batchen, Forget me not: photography and remembrance, Van Gogh Museum, Princeton Architectural Press, Amsterdam & New York, 2004, p 10.

- Pamela Pattynama, ‘Tempo doeloe nostalgia and brani memory community: the IWI collection as a postcolonial archive’, Photography and Culture, vol 5, 2012, pp 268–77.

Images for this essay

|

| |

|

| |

|

| #SP 3-02 & 3-03: 3 images above from Jan Grader presentation album 1933 |

| |

|

| #SP 3-04: The lights of Pasar Gambir in the Jan Grader presentation album 1933 |

| |

|

| #SP 3-05: Modjo-Agoeng album 1915–20 |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| #SP 3-06, 3-07, 3-08: My three sisters, Student??!!! and My ‘sister’ in the Samsoedin family album c 1933 |

| |

|

| #SP 3-09: Wally Enthoven album c 1931–34 |

| |

|

| #SP 3-10: The new Hudson in the Wally Enthoven album c 1931–34 |

| |

|

| #SP 3-11: Couple posing before their utility vehicle in an Indo-European family album |

| |

|

#SP 3-12: Letter from an Indo-European family album,

‘Dear John, What a lovely long letter from you! Many thanks! …’ |

|

Return to Introduction and the Table of Contents

|