|

Table of Contents

A Change of Pace

professional, pictorial and personal photography 1890s – 1940s

Gael Newton AM (2014/2025)

|

| #GN 2-1: Unknown photographer, The Berg, de Yong and Stubbe families and friends 1911 |

In the original catalogue, 18 photographs were placed throughout this essay.

For this online version, besides the one above, the images have been placed together lower down this page – after the footnotes.

When people pose within a photograph they may pose new possibilities for themselves,

but they also present these possibilities for those who may view the image and imagine themselves in its frame.

Karen Strassler, Refracted visions, 2010

From around 1900, the worldwide distribution of commercial dry plates, easy-to-carry cameras and roll film processing for the amateur greatly expanded the numbers of photographers at work. The camera could be used to capture daily life and became a companion at home and away.

Early twentieth-century cinematography also created a taste for more animated and varied images, which shaped the way photographers and their clients approached the still image. Cheap picture postcards and the halftone process which allowed for fast, economical, integrated printing of photographs with text similarly expanded the kinds of photographic images in circulation.

These images opened up new visual and social possibilities to both Asian and European communities in the Dutch East Indies.

Over the next decade or so, European and Chinese bookstore publishers expanded their photographic products, while hotels and shipping companies worked in collaboration with favoured local studios. International photography suppliers, chiefly Kodak, established agencies across Asia and assisted chemist shops and others, including Chinese operators, in the processing business.

The pictorial revolution envisaged by Henry Fox Talbot in England in the 1840s was in place and photography was on the path to being the chief illustrative medium of the modern age. The graphic and photographic arts merged. Pictorial magazines in this period routinely added decorative touches to plates made from photographs, but it was a two-way street: illustrations became more lifelike and animated, and photographs became more artistic. As public taste for an informative and effective promotional photograph increased, so too did the personal identity of the photographer.

This trend reflected claims that camera art could be personal in vision and execution, as advocated by the new art photography movement known as Pictorialism. Centred in Europe and then America, the art photographers had a network of exhibiting societies, salons and specialist publications.

In Indonesia in the nineteenth century, no photographic societies were active, but amateurs had been taking lessons from professionals since the 1860s. Indische Lux, a magazine for amateurs, lasted a few issues in Jakarta in 1902. The Dutch Indies Amateur Photographers Association was started in Jakarta in 1923, and salons based on the international model were held in 1923 and 1925, paralleling similar activities in Australia.

Most of the work of these societies appears to have vanished. While the internationally active Pictorialist movement did not evolve as strongly in Indonesia as it did in Australia and Japan in the early years of the twentieth century, some of the longest established Dutch East Indies photographers did respond to the challenge and stimulus of the new visual tastes and economy in aestheticising and reforming the image of the ‘Garden of the East’ for the new century.

Largely hidden from public view were the Asian amateurs, including those who turned professional after 1900, such as brothers Tan Gwat Bin (1884–1949) and Tan Bie Je. The majority of twentieth-century amateur photographers would be upper and middle-class Chinese Indonesians.1

In 1897, when American travel writer, National Geographic Society Board member and amateur photographer Eliza Scidmore (1856–1928) published her popular travel book Java: the Garden of the East, she drew readers’ attention to the tourist guide to the Dutch East Indies recently published by the Royal Packet Navigation Company (KPM, Koninklijke Paketvaart Maatschappij).2

Both publications were photographically illustrated, although the photography was not attributed. They targeted English speakers who had not yet discovered the charm of the Dutch East Indies but who might have become interested through the living Javanese villages and performers at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1889 and the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893.3

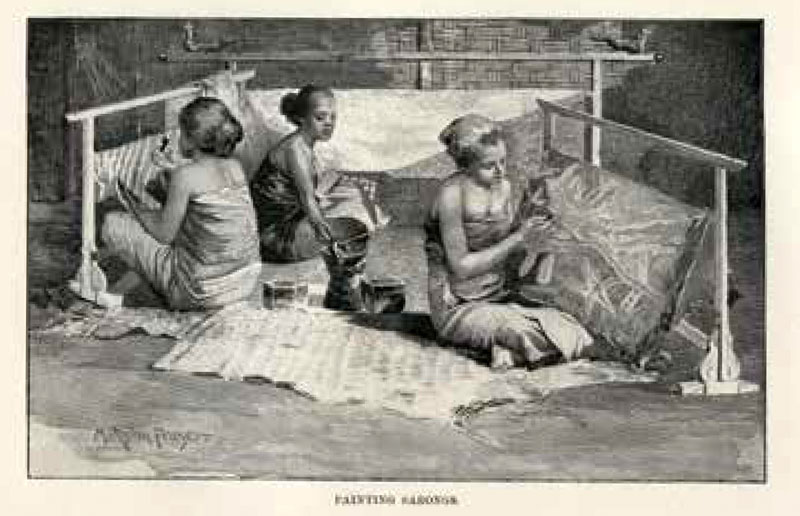

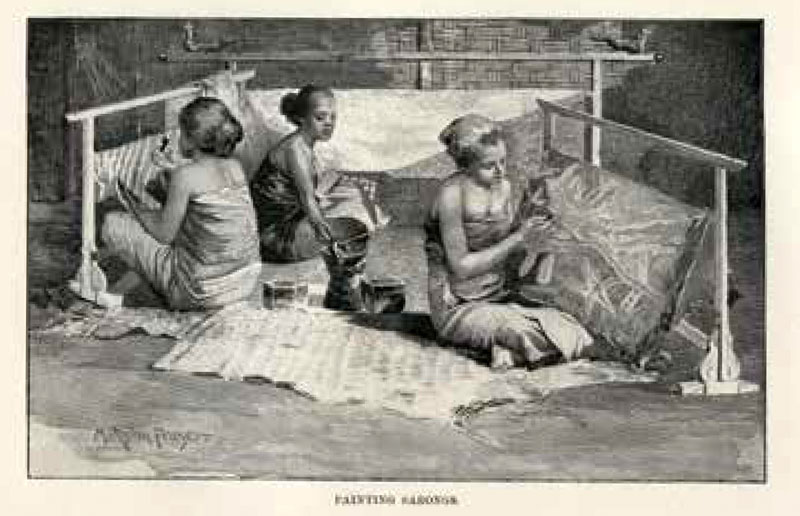

For French travellers, there was Jules Leclercq’s Un sejour dans l’ile de Java of 1898, which had quite good halftone photographs, similarly uncredited, from Kassian Céphas (1845–1912) and other studios. Before 1900, it was typical that such books acknowledged engravers but not photographers.

The anonymity of photographers, however, would become a thing of the past in the next decade. By the turn of the century, the elderly Céphas had considerable recognition, which aided him in securing equal legal status as a European for himself and sons Semuel and Fares in 1891 and to become a Freemason in 1892.

He was also made an extraordinary member of the Batavian Society of the Arts and Sciences (Bataviaasch Genootschap der Kunsten en Wetenschappen) in 1892 and an honorary member of the Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies (KITLV, Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal‑, Land- en Volkenkunde) in Leiden in 1896.

Finally, from the Dutch Crown in 1902, he received an Honorary Gold Medal of the Royal Dutch Order of Orange-Nassau in recognition of his work on Javanese cultural heritage. No other Asian colonial‑era photographer received any comparable level of official recognition, other than perhaps Deen Dayal in British India. Kassian retired from the studio in 1905 but continued in service at the Yogyakarta palace. After Kassian died in 1912, his son Sem managed the studio until he died accidentally in 1918.

Sem’s authorship is attached to a view of tiny figures of Chinese bird-nest collectors climbing down vine ladders to the sea cave at Ngungap in Gunung Kidul regency, and he may have collaborated on other gentle landscapes of the region’s coast. A wonderfully coloured image of a Javanese lady is attributed to Sem, suggesting that he was likely behind the studio’s popular series of Javanese beauties that circulated as postcards.

These postcards have a relaxed charm and personality in contrast to the blank stares and soft-porn aesthetic of other publishers.4 The honours shown to Kassian Céphas reflected the new Dutch Ethical Policy (Ethische Politiek) that aimed to develop a class of Indonesian leaders loyal to the Crown. An examination of his work from this period suggests he had a new sense of self and incipient nationalist spirit.5

Photographers on the whole leave few self‑portraits, and Céphas is unique in Indonesia in making the first. He also stands out for the frequency with which, from around 1890, he places himself in photographs of significant sites. His prints were usually titled and signed in the image area and his bearded figure in Javanese dress and cap would have been easily recognised, in Yogyakarta at least. It is as if the positioning was a gesture both personal and political. He was perhaps also seeking his own union with princess Loro Jonggrang of legend and the indigenous cultural values in which the land and spirits harmonise.

A new generation of studios

From the 1890s, studios run by Chinese and Peranakan (Chinese- Indonesian) appeared in increasing numbers. Photographic companies were making studio processing easier and cheaper, and these local studios were more welcoming to passing trade from all classes.6 A family portrait was within the reach of a larger pool of customers and had the prestige of something previously restricted to the elite.

A noticeable change in studio names from the 1890s is the number of Chinese-run portrait studios, which developed rapidly as processing and supplies became easier with support from international photographic companies. They catered to all comers while maintaining their high-class clientele. One of the first Chinese studios was Tan Tjie Lan (active 1895–1935) in Jakarta, which provided views and society portraits and won medals that, like the European studios, were immediately splashed on his cards.

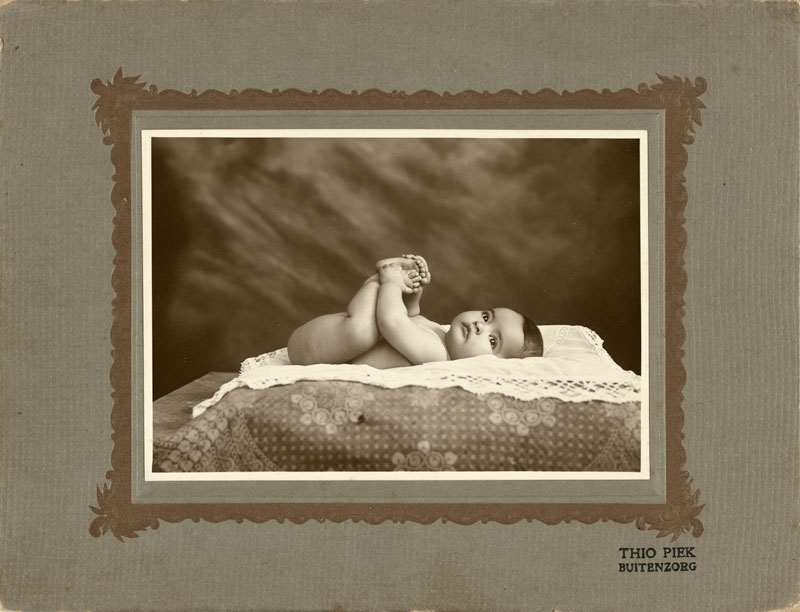

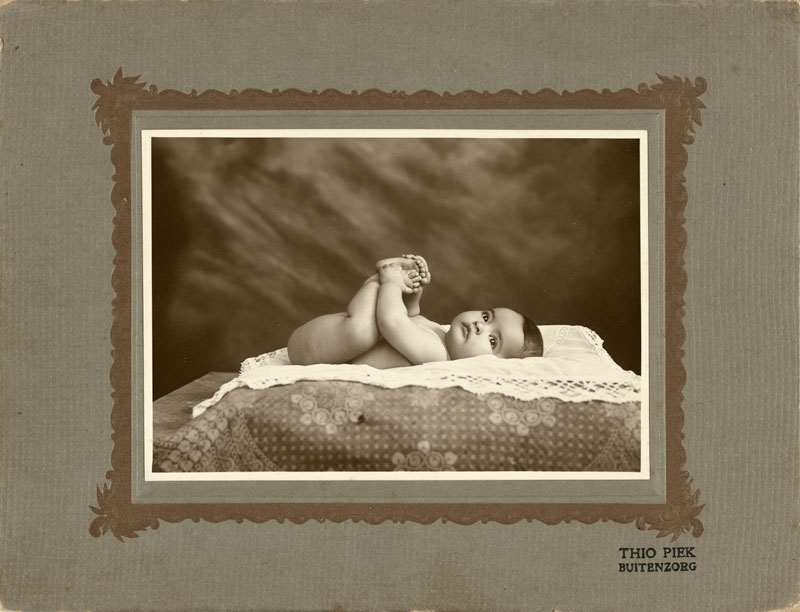

Others were Thio Piek (active 1920–1940), who ran a busy studio store in Buitenzorg (now Bogor) and made fine baby pictures; Beng Ik Tjiang (active 1920–1930) in Bandung, who made fine military portraits; and prominent Jakarta merchant and postcard publisher Tio Tek Hong (active 1902–1940), who may have commissioned a series of evocative tableaux with something of the character of Hollywood film stills.

These Chinese or Peranakan businesses, for political and economic reasons, used romanised Indonesian forms of their names.

American anthropologist and photographer Karen Strassler recently made a pioneering study of amateur photographers and vernacular trends that existed before the independence of Indonesia, retrieving the lost picture of the nature and extent of activity from the 1920s to the 1940s.7

Photography was a purveyor of all things modern as well as a means to raise the consciousness of possible future identities. Increasingly, both the dress and the stance in studio portraits expressed the modernity and aspirations of young nationalists. One of the few gifted amateurs of this era who has a record that has survived is Peranakan Tan Gwat Bin, a publisher of cards and postcards whose work was published in De Orient magazine.

He was one of the first Chinese-Indonesian to cut off his queue in the 1920s.8 Future research will surely broaden the understanding of the activity of art photographers in Indonesia beyond the tourist trail.

The grand scale of modern times

In face of the millions of new images from all amateur and professional quarters, many turn-of-the-century studios, in both Australia and Indonesia, applied a more aesthetic and design approach to modern subjects.

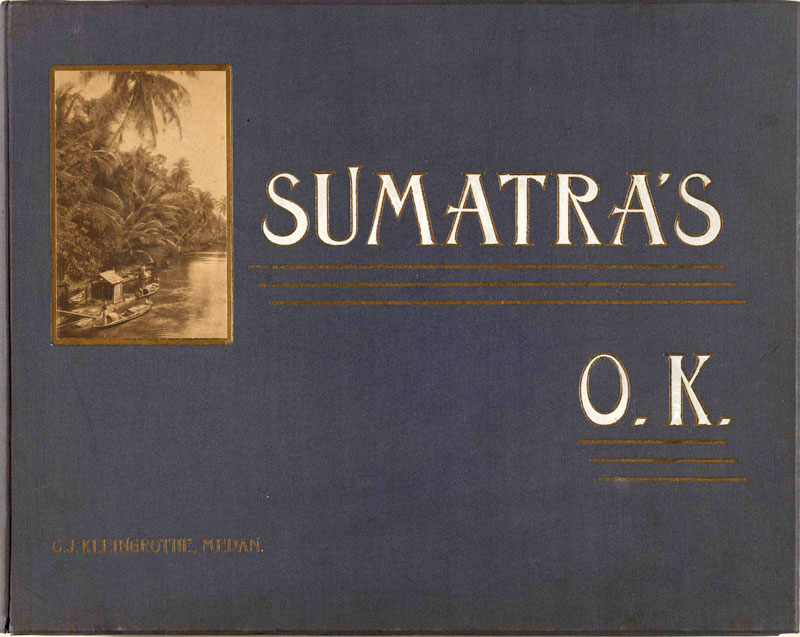

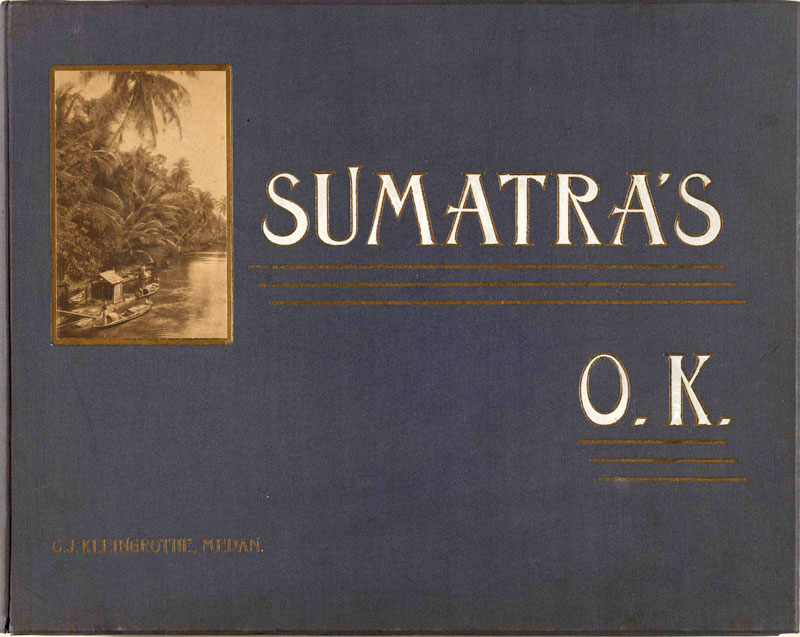

The Kleingrothe studio was one of the first firms to produce high-quality photogravure portfolios of natural and constructed features in north-east Sumatra. The lavish folios, Sumatra and Sumatra’s OK, or Sumatra’s Oostkust (East Coast), were packaged in smart blue linen cases and included some sixty photogravure plates printed in blue, brown and green ink. They imparted charm to scenes of workers and tribal cultures, and a few pretty girls for good measure unified the picturesque with the proprietorial.

Kleingrothe’s folios were hugely popular, running unchanged through ten editions in four languages between 1898 and 1925. By 1910, O Kurkdjian & Co chief photographer George Lewis was making picturesque views and moody twilight scenes around the resort area of Tosari in the highlands of East Java. These closely followed styles favoured by the Pictorialist art photographers in Europe.

Lewis also published three folios of views of the Dutch East Indies with rich dark-toned brown photogravures on resort areas of Tosari and Garut. ‘Geo P Lewis’ was printed under each image. Lewis returned to Britain to aid the war effort in 1916, making a few return visits in the 1930s. He continued to publish his Java images in the American journal Camera Craft in February 1934 and in the Dutch East Indies section of JA Hammerton’s multi-volume Peoples of all nations: their life today and the story of their past first published between from 1922 and 1938.9

Scale in these years was not just a matter of folios. The Kurkdjian studio produced metre-wide matt gelatin silver prints showing stages of sugar production in Java. Most ambitious and influential of all was the Dutch printers Kleynenberg & Co in Haarlem, who produced a series of one hundred and fifty huge (73 x 60 cm) zinc photogravures of the Dutch East Indies.

The series, Platen van Nederlandsch Oost-en West Indie en Suriname, was issued between 1911 and 1913 for use in schools in the Netherlands. The images were supplied by the Topographic Unit (Topografische Dienst) in Jakarta and credited to their photographer, Padang born French-Javanese photographer Jean Demmeni (1866–1939), although they were actually drawn from a number of major studios.

Mezzotint-like collotype was used by Jean Jacques Vink (1883–1941) in 1908 for his studies of the Buddha statues at Borobodur, while photogravure printing was used by Haarlem printers H Kleinmann & Co (active 1896–1902) for a series of rich brown photolithographs on plantations, plants and peoples for the educational portfolios issued by the Kolonial Museum in Haarlem from 1896–1901.

Pictorial and promotional

Photographers played a part in the genre of painted and graphic art known as Mooi Indie (Beautiful Indies) art from the 1930s (although evident decades before), which collectively reinforced an image of timeless tropical landscapes, native beauties and contented rural peasantry with no trace of modern lifestyles, industry or exploitation. The trend synchronised with the romantic aesthetic of Pictorialist photography, which was also recruited by advertisers and editors to glamorise their products and promote places and people.

Alliances between hotels, resorts and cruise ships and the new tourist organisation in Jakarta boosted the sales of souvenir images as well as illustration work for the photographic studios. Itineraries advertised available darkrooms, photo suppliers and scheduled stops at the grand white corner studio of Ohannes Kurkdjian in Surabaya, the principal agent for Kodak supplies in Indonesia.

After the studio founder’s death in 1903, George Lewis continued as O Kurkdjian & Co’s chief photographer until 1916, after which the studio passed through various owners until 1935. The firm made a range of products for the tourist market, even supplying photographic materials for amateurs. A new appreciation for photographic art is evident in Thomas H Reid’s preface to his 1908 book Across the equator, a holiday trip in Java, where he thanks ‘Mr GP Lewis’ for providing illustrations of ‘the finest and most artistic collections we have seen of landscape work’.

In 1912, the Royal Packet Navigation Company (KPM) even published Isles of the East: an illustrated guide, a travel brochure made specifically for the Australian traveller and illustrated with O Kurkdjian & Co photographs. The following year, the company commissioned Australian professional Frank Hurley to photograph in Java.10 He was just back from the well-publicised Australian Antarctic Expedition with Douglas Mawson. Hurley published his Java images in the February 1914 issue of the Australian arts and literature magazine The Lone Hand.11

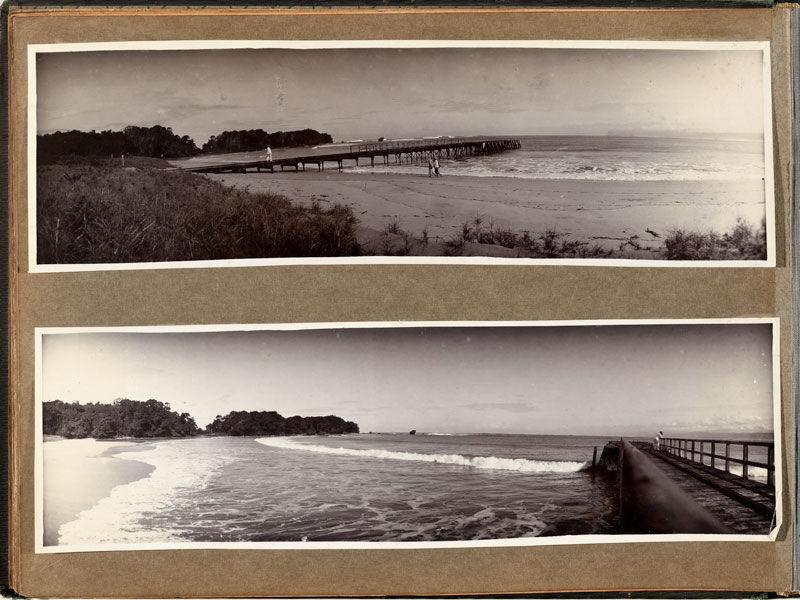

From the O Kurkdjian & Co, under Lewis’s training, came the only woman professional photographer of note in colonial Indonesia, Thilly Weissenborn (1889–1964), and one of a very few anywhere in Asia with her own studio.12 In 1917, Weissenborn was asked by amateur photographer Dr DG Mulder to run the GAH Photo Studio in his Garut pharmacy in the rapidly developing health resort town in West Java.

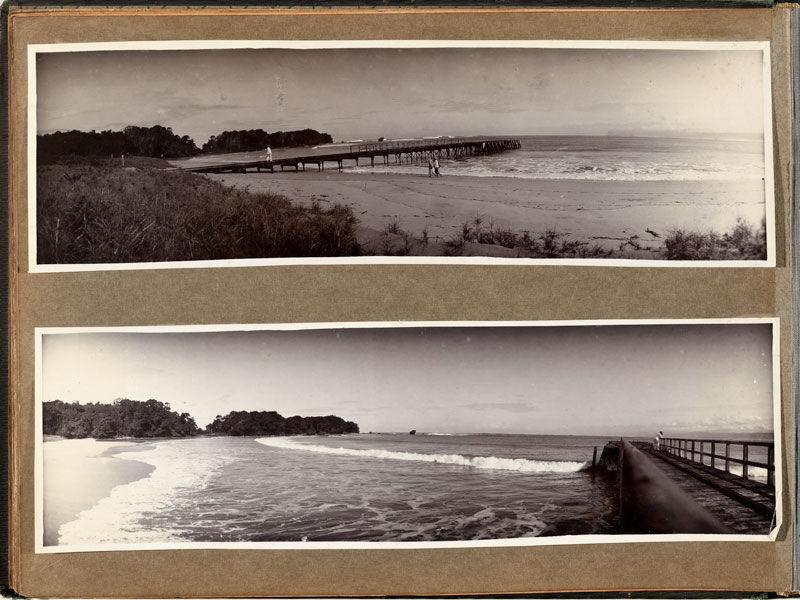

She then acquired the studio in 1920 and renamed it Lux Studio. Throughout the 1920s and early 1930s, her studio produced a steady stream of work from Java, Sumatra, Lombok and Bali for souvenir albums, the most popular of which Weissenborn published in a portfolio on Bali in rich photogravure.

‘Th Weissenborn copyright’ appears under each plate. As part of the generation of women taking up the profession in their own names, rather than as the backroom assistants they had been since the mid nineteenth century, Weissenborn was typical in running a small operation but unusual in not confining her activity to studio portraiture. She clearly loved to work outdoors like her younger Australian contemporary Olive Cotton (1911–2003).

Her work is not modernist but is suffused with an inner luminosity and gentle naturalist Pictorialist mood. Weissenborn also trained several Indonesian women assistants.

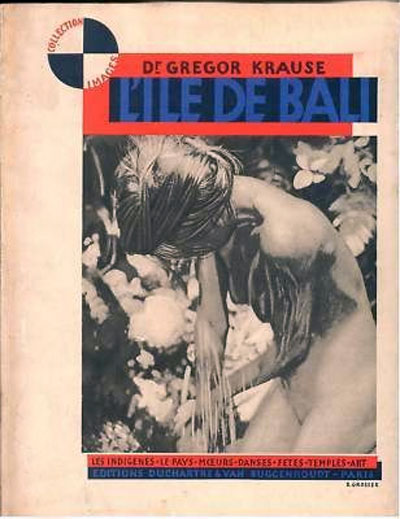

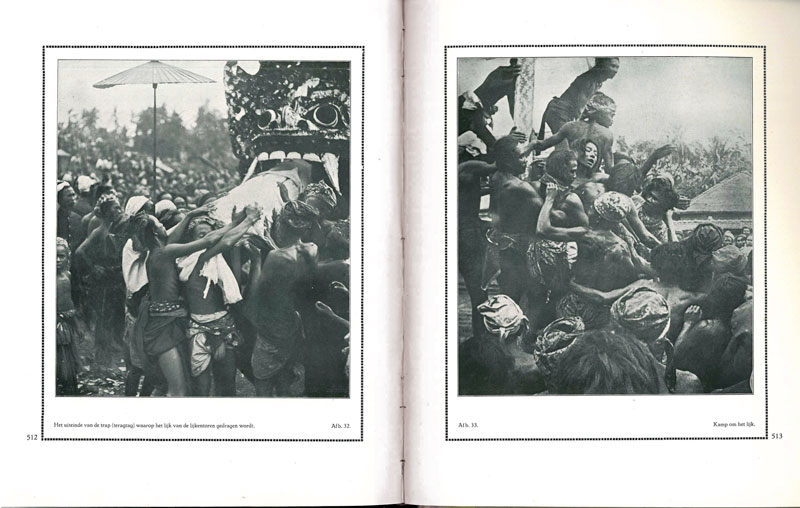

Dr Krause, an inspired amateur

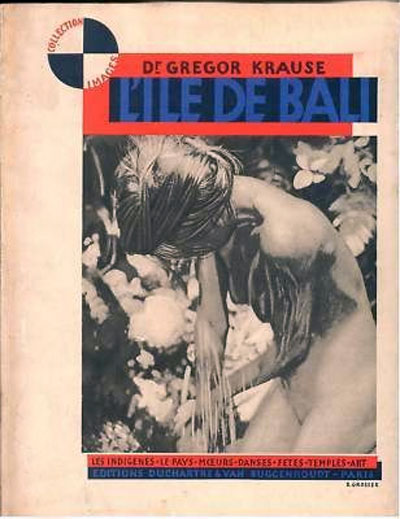

Of greatly under-appreciated significance today is the work of Gregor Krause (1883–1959) who used a small hand-held German camera during a residence in Bali in 1912 to record what seemed to him the idyllic life of the people around him.13

‘Everything is beautiful, perfectly beautiful—the bodies, the clothes, the gait, every posture, every movement’, he recalled, ‘nobody even noticed I was taking them’.14

His Bali images were sensuous and erotic—perhaps more than he saw but, arguably, not sly and not predominant by number considering his entire output. They reflected the modern nature philosophy and body culture prevalent in Germany in the early years of the twentieth century.

Krause’s Bali work is truly remarkable for its anticipation of the photo-essay format developed first in German illustrated magazines in the 1920s. The First World War intervened, but in 1920 Asian art historian and director of the Folkwang Museum Karl With (1891–1980) published a two volume set, Insel Bali: Land und Volk (Bali: land and people) and Insel Bali: Tanze, Tempel und Feste (Bali: dance, temples and festivals) in the series Folkwang-Verlag on Asian culture.

The set rapidly went to a second edition, a single abridged poorer quality volume in 1922, a revised German edition in 1926 and French translation in 1930.15 It also captured the attention of numerous artists and writers. The Austrian novelist Vicki Baum who visited the island in 1935 and published her novel A tale of Bali in 1937 was inspired to do so by a set of Krause’s Bali images she possessed.

They were, she wrote, an escape from ‘the horrors my generation was exposed to—war, revolution, inflation, emigration’.16 Baum acquired the photographs in 1916 presumably, they were in a portfolio Krause was using to find a publisher. Krause published detailed, informed articles and research in Nederlandsch-Indie: Oud en Nieuw, which captured the reportage flow of his work and the look of the modern picture magazine ‘photo-essay’ being developed in the 1920s in Germany.17

The photographs in his portfolio on Borneo flora and fauna, published in 1926, are among the finest animal and nature studies of their day. Krause brought the amateur art photographer’s quest for spirit and beauty, in the manner of a number of early twentieth-century photographers like Edward S Curtis (1868–1952) and Robert J Flaherty (1884–1951), to a genre now defined as ethnographic Pictorialism.18

The portrait

The style of portrait photographs for both European and Asian clients in Indonesia in the first decades of the twentieth century also followed the artistic trends of Europe with matt surfaces and dark tones like Pictorial salon photographs, often mounted on multicoloured dark papers. For the most part, little effort was made to locate the portraiture in the tropics and the images were interchangeable with those of relatives in Europe—perhaps that was the point.

A new stylishness, however, can be seen in studio portraiture in the 1920s and 1930s. Norwegian Hjalmar Bodom (1866 – after 1935), formerly of London, Singapore and Penang, brought European high-society aplomb to his portraits of clientele in Bandung from 1925 to 1935.

This prosperous city in the cooler climate was among the most modern in Indonesia and its sophistication was best captured by the firm of partners Charls & van Es & Co in Bandung. The firm, also with a branch in Jakarta, prided itself as specialist in ‘MODERNE FOTOS’. Immaculately composed and lit and printed on matte papers, the confidence and also hedonism of an era is captured in the many images of gatherings, parties and fancy dress events shown in studio photographs of the 1920s, which was one of the high points of colonial economy in Indonesia.

Looking for ‘the last paradise’

Along with the tourists in the Royal Packet Navigation Company (KPM) boats in the 1920s and 1930s came artists and writers and photographers seeking a new life or some kind of postwar renewal in the paradise of Bali. They were forerunners to the hippies of the jet age who descended on the beach at Kuta in the 1970s.

Little is known of one of the earliest, the gifted Japanese S Satake, who arrived in Bali in 1902 from Tokyo as a dealer in Japanese prints. By 1912, he had become an accomplished photographer under the studio name Tosari and travelled around in his photographic studio caravan. His images drew inspiration from the glimpses of distant mountains and lively figure placement of ukiyo-e print styles.

Satake was quite prolific. He provided illustrations for the 1918 travel booklet See Java: the Garden of the East for a motor touring company and the booklet Tengger en de Tenggereezen (Tengger and the Tenggerese) by JE Jasper around 1928. In 1935, his work was reproduced under the name KT Satake in the large photo book Java Sumatra Bali. The latter included a number of colour autochrome portraits, although colour work from Asia is very rare for this period—the feast of colour photo books was to come with the printing and film advancements of the 1960s.19

The Russian-born German painter, musician and amateur photographer Walter Spies (1895–1942) arrived in Java in 1923 and then Bali in 1927 and became involved with attracting tourists and assisting researchers. He also co-founded arts cooperative Pita Maha. His photographs were not just documentary; they appeared as attractively worked-up plates in the Royal Packet Navigation Company’s posh tourist guide Bali: godsdienst en ceremonien (Bali: gods and ceremonies) in 1930.

Spies acted as a guide and promoter of Bali as ‘the last paradise’ but also collaborated with researcher Beryl de Zoete in 1938 on a scholarly study Dance and drama in Bali. His influence on others in creating the Bali myth was strong. Mexican artist Miguel Covarrubias (1904–1957) and his dancer and photographer wife Rosa (1897–1962), inspired by Krause’s books, visited Bali for the first time in 1930.

During their second visit in 1933, Spies assisted them, and Covarrubias soon published his popular Island of Bali in 1937, which in turn inspired others to visit. And so it went on throughout the 1930s, with boatloads of foreign celebrities and artists visiting Bali, including French born American filmmaker, photographer and adventurer Andre Roosevelt (1879–1962).

Roosevelt provided illustrations for Hickman Powell’s travel book The last paradise in 1930 and made two films on Bali, Goona-Goona, an authentic melodrama of the island of Bali and Kriss, in two-strip Technicolor with Belgian documentary filmmaker Armand Denis (1896–1971) both released in 1932.

Goona-goona (Guna guna), meaning ‘magic spell’ in Balinese, became a Hollywood film category. The films in the category were defined by their sentimental scripting thinly veiled under the guise of ethnographic interest, showing actual footage of tropical customs and bare-breasted native women. This was in contrast to the pure costume fantasies such as Mata Hari of 1931, starring Greta Garbo.

Among artist photographers who passed through Bali around 1930 was Hong Kong–born Portuguese dentist Arthur de Carvalho (1890–1969), who arrived from Shanghai around 1935. Carvalho’s images are striking for their sense of the camera as an invisible eye, right in among the action. This was possibly by using a telephoto lens—as a short-term visitor he could hardly have built up a relationship with the locals. The manipulation of tone and mood in his warm-toned Pictorialist-style exhibition prints gives the images the look of a film set.

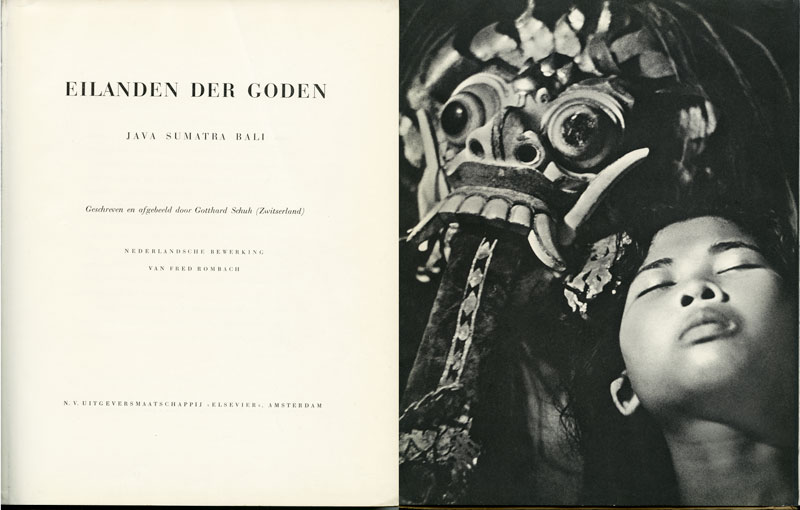

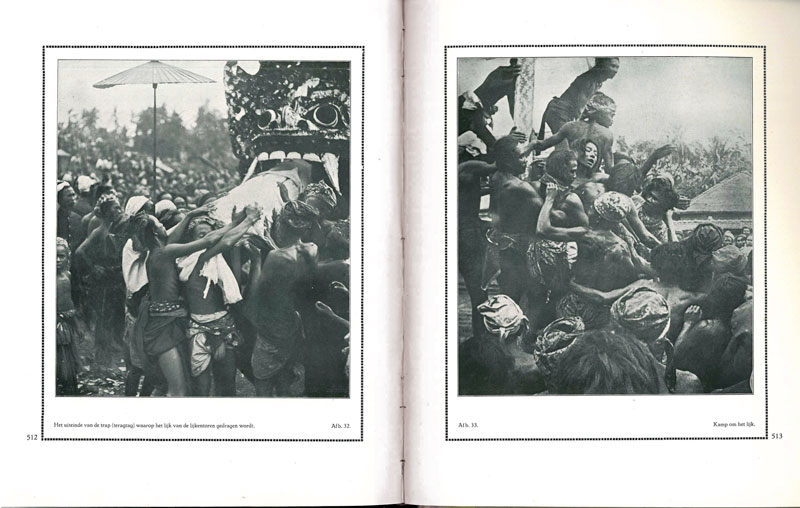

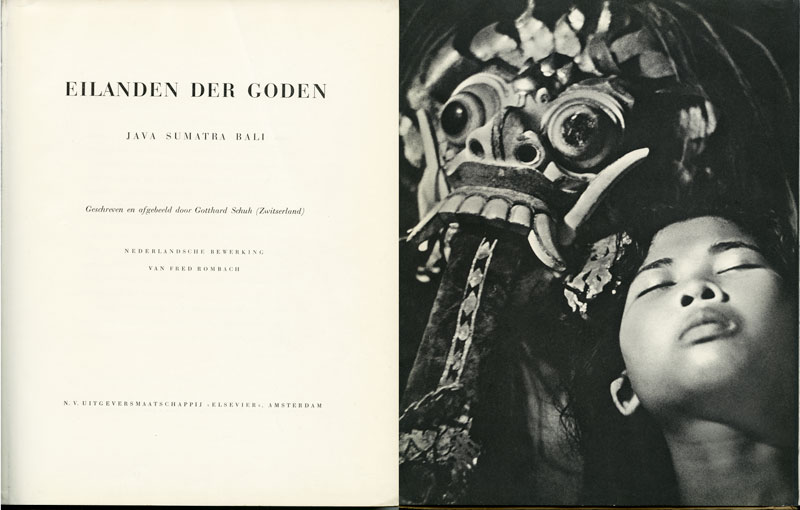

The first to produce modern high-quality large-format travel photo books were American photographer, explorer and journalist Philip Hanson Hiss (1910–1988) and Swiss photojournalist Gotthard Schuh (1897–1969) in 1941. Hiss’s book Bali was a modernised textbook with pictures, while Schuh’s best seller Inseln der gotter: Java, Sumatra, Bali (Islands of gods: Java, Sumatra, Bali) was a photo book with text following the trend of animated layouts of word and image, single- or double-page spreads, of photo-essays in picture magazines such as Life. Schuh had visited Indonesia in 1938, and his closeups taken at unusual angles have clear modernist influences.

The role of movies and newsreels is considerable in the 1930s and 1940s in fuelling public expectation for more animated imagery in still photography and in establishing a Hollywood type of the oriental glamour. Similarly, dancers who were based overseas, including Raden Mas Jodjana and Indra Kamadjojo, promoted Westernised versions of traditional Javanese and Balinese dance culture.

The vernacular mirror

By the 1910s, modest-scaled commercial photographic albums of black paper pages with special corners to affix the photographs replaced the nineteenth-century embossed leather-covered albums for carte-de-visite and cabinet-card portraits. As with other photographic industry developments, family albums were fairly uniform across the world. Dutch East Indies albums often have Japanese or batik patterned cloth covers to signify life in the tropics. They present the same images, as elsewhere, of (affluent) happy families, whether European, Asian or mixed‑race, but with the addition of a cast of named and unnamed native servants as part of the household.

Albums from Dutch families in Indonesia tend to show off interiors more than European examples, perhaps since distant family members would never see their tropical home. They also mix the corporate and plantation images with the domestic scenes in unconscious recognition of the economic source of the family’s wellbeing. Unlike the rigid slots for portraits in nineteenth-century albums, the compilation, rearrangement and inscribing of the modern family album could show the creativity, wealth and success of each compiler. Some arrangements of photographs on the page harmonise with the patterns of wall plaques and posing.

They reflect the status, power and self-image of the assembler and even become ‘plays’ scripted in captions. The sequencing and doubling of images taken a few seconds apart mimic the layouts of pictorial magazines. Some family photographers were engaged and technically competent and occasionally gifted in some aspect of album making such as Wally Enthoven, whom we see grow from girl to a young woman in her neatly assembled album started in 1931.

By its nature, a family album was meant to be shared and handled, but Wally could not have imagined her life would be viewed by strangers in 2014. Thousands of dispossessed family albums from early to mid twentieth-century colonial Indonesia ended up in estate and book auctions in the Netherlands in the 1980s.

Some hundred of these are now in the National Gallery of Australia’s colonial Indonesian photography collection, and their histories can be shared with a much wider audience, including historians, researchers, the interested public and even genealogists.

This was not the grand commercial application of photography that Henry Fox Talbot envisaged over a century before in the 1840s for his invention of photography on paper and photomechanical methods of reproduction. Talbot might possibly be as intrigued as we are by the entertaining, challenging and enriching story such diverse photographs made between the 1850s and 1940s tell of the history of Indonesia and the first century of photography in Southeast Asia.

Introduction and the Table of Contents

Footnotes

- Only a few European amateurs in Indonesia had work featured in the London magazine Photograms of the Year from 1894 to 1960, compared to considerable numbers of Japanese amateurs. See also, ‘Amateur visions’, chapter one, in Karen Strassler, Refracted visions: popular photography and national modernity in Java, Duke University Press, Durham, 2010. Strassler’s is the first study of amateur art photography in Indonesia that highlights the indigenous perspective.

- JF van Bemmelen and GB Hooyer, Guide to the Dutch East Indies, composed by invitation of the Royal Packet Navigation Company (KPM, Koninklijke Paketvaart Maatschappij), trans BJ Berrington, Luzac & Company, London, & G Kolff & Company, Batavia, 1897. This was the first of many editions and variants by the shipping company KPM, formed in 1888.

- See also Marieke Bloembergen, Colonial spectacles: the Netherlands and the Dutch East Indies at the World Exhibitions, 1880–1931, trans B Jackson, Singapore University Press, Singapore, 2006.

- A similar phenomenon can be seen in the work of Céphas’s Indian contemporary Deen Dayal, whose portraits of Indian dancers have presence and personality compared to the usual ‘native types’.

- Strassler, ‘The aura of power: Ratu Kidul’s photographic appearances’, paper presented at Cornell University, New York, USA, 8 March 2012, to be published at time of printing in Comparative Studies in Society and History, vol 56, no 1, 2014.

- See Anneke Groeneveld and others (eds). Toekang potret: 100 jaar fotografie in Nederlands Indie 1839–1939, Fragment Uitgeverij, Amsterdam, & Museum voor Volkenkunde, Rotterdam, 1989, for listings of the 471 studio and personal names: 265 have European-style names of which some 48 personal names are of Dutch character; 72 are Japanese names; and 134 are Chinese names (many in romanised Indonesian form).

- See Strassler, Refracted visions, 2010

- Strassler, ‘Modelling modernity: ethnic Chinese photography in the ethical era’, in S Protschky (ed), ‘Camera ethica: lenses on modernity, civilisation and being governed in late-colonial Indonesia’, book manuscript, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, forthcoming 2014.

- See JA Hammerton (ed), Peoples of all nations: their life today and the story of their past, abridged, 2 vols, Amalgamated Press, London, 1934, pp 997–1013 & 3677–96.

- The Royal Packet Navigation Company does not appear to have used the images but did bring out Isles of the East: an illustrated guide in 1914 for the Australian market.

- Frank Hurley, ‘Java: some notes and pictures by Frank Hurley’, The Lone Hand, 2 February 1913, pp 189–91.

- Other women worked in or owned studios. Weissenborn worked with a Mrs Weustman in 1913, and Jean Brandt had a studio in Medan, North Sumatra, from 1915 to 1920.

- Annabelle Lacour, ‘La representation de Bali dans le livre photographique: de Gregor Krause a Henri Cartier-Bresson 1920–1950’, masters thesis, Ecole du Louvre, 2013.

- Gregor Krause, quoted in Hugh Mabbett, ‘About Gregor Krause’, in Bali 1912: photographs and reports by Gregor Krause, H Mabbett (trans), January Books, Wellington, 1988, pp 8–9.

- The two-volume set was first published in English as a single book, Bali 1912, in 1988. See assessment of Krause’s books, in terms of German photo books, by Rainer Stamm, ‘Vom imaginaren Weltkunst-Museum zur Neuen Sachlichkeit: Folkwang-Verlag, Auriga-Verlag, Folkwang- Auriga Verlag’, in M Heiting and R Jaeger (eds), Autopsie: Deutschsprachige Fotobucher, 1918 bis 1945—Band 1, Steidl, Gottingen, 2012, pp 83–5.

- Vicki Baum, cited in Jojor Ria Sitompul, ‘Visual and textual images of women: 1930s representations of colonial Bali as produced by men and women travellers’, PhD thesis, University of Warwick, 2008, p 57.

- Julie A Sumerta, ‘Interpreting Balinese culture, representation and identity’, MA thesis, University of Waterloo, 2011.

- Heather Waldroup, ‘Ethnographic Pictorialism: Caroline Gurrey’s Hawaiian types at the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition’, History of Photography, vol 36, no 2, 2012, pp 172–83.

- National Geographic published the first colour images of Asia and autochromes of Bali by Franklin Price Knott (1854–1930) in March 1928 and by Maynard Owen Williams (1888–1963) in March 1939. Tassilo Adam (1878–1955) also made autochromes in the 1920s.

Click here for the Introduction & the Table of Contents

Images for this essay

|

| #GN 2-2: Tjantian, Insulinde Fotographisch Atelier Surabaya couple and child in their carriage with Indonesian servants c 1915 |

| |

|

| #GN 2-3: H Ernst & Co Sumatra postcard of Chinese opera performers c 1899 |

| |

|

| #GN 2-4: Kassian Céphas (after) Painting sarongs, engraved plate by Malcolm Fraser in Java: the Garden of the East 1897 |

| |

|

| #GN 2-5: Sem Céphas Kassian C.phas at Kawah Candradimuka, a volcanic crater in Central Java c 1895 |

| |

|

| #GN 2-6: Sem Céphas Javanese woman c 1900, painted photograph |

|

| |

|

| #GN 2-7: Thio Piek Baby portrait c 1910 |

| |

|

| #GN 2-8: Unknown photographer Pasar Baru, Jakarta c 1900 |

| |

|

| #GN 2-9: Charles J Kleingrothe Case for his Sumatra’s OK c 1905 edition |

| |

|

| #GN 2-10: Charles J Kleingrothe Medan. Kesawan Street from south c 1900, from his Sumatra’s OK c 1905 edition |

| |

|

| #GN 2-11: Thilly Weissenborn Cilaut, Eureun Bay, Cikelet, West Java c 1920 |

| |

|

| #GN 2-12: Gregor Krause L’Ile de Bali 1930 |

|

| |

|

| #GN 2-13: Gregor Krause Temple festival in South Bali in Nederlandsch-Indie: Oud en Nieuw, July 1928 |

| |

|

| #GN 2-14: Charls & van Es & Co Mother and child c 1915 |

|

| |

|

| #GN 2-15: KT Satake Women on a road in Bali c 1928 |

| |

|

| #GN 2-16: Gotthard Schuh Eilanden der goden 1941 |

| |

|

| #GN 2-17: Andre Roosevelt Legong dancer [named Ni Pollok], Bali 1928 |

|

| |

|

| #GN 2-18: Dutch-Indonesian family album c 1925–30 |

Return to Introduction and the Table of Contents

|