|

Table of Contents

Essay One:

Silver streams

photography arrives in Southeast Asia 1840s – 1880s

Gael Newton AM (2014/2025)

|

| #GN 1-1: Walter B Woodbury River scene, Java 1860, woodburytype plate from his Treasure spots of the world 1875 |

In the original catalogue, 24 photographs were placed throughout the essay.

For this online version, except for photograph above,those images have been placed together lower down this page – after the footnotes.

The means have been found to raise sunlight itself to the rank of an artist, and to reduce faithful depictions of nature to only a few minutes work. Opregte Haarlemse Courant, Amsterdam, 13 January 1839

Around 1840, ships crossing the Indian and Pacific oceans carried news of mirror-like photographs on metal plates perfected by the French diorama artist Louis Daguerre (1787–1851) and of soft ‘photogenic drawing’ impressions and tiny camera images on light-sensitive paper developed by English gentleman scientist Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877). In 1841, Talbot patented his superior ‘calotype’ process, which used a translucent photograph on paper as the negative from which multiple positive prints of the image could be made.

This quest for replication, aligned with the production-line mentality and global reach of the Industrial Revolution in Europe, would be the real future of photography. The commercial launch of photography dates from 19 August 1839 in Paris when the French Government made the technical details of the ‘daguerreotype’ freely available to the world.

By early September 1839, cameras, manuals and apparatus from Paris were on the high seas, sometimes accompanied by practitioners who had received a crash course in their use. For many of those who joined the new vocation of ‘daguerreian artist’ or ‘photographist’ (among other variants), their childhood picture books and magazines had already created desires to see exotic foreign lands.

When launched, photography on metal or paper could only record inanimate objects but rapid technical developments saw the world’s first portrait studio open in London in 1841. The novelty of a photographic likeness was initially only for the affluent, but the lure of such vanity-driven income propelled itinerant daguerreotypists to the network of European colonial ports in Asia.

In the very first years of photography amateurs were as numerous as professionals, and the earliest surviving images of Southeast Asia are daguerreotypes made in 1844 in Singapore, Macau and Saigon by the French trade negotiator Jules Itier (1802–1877).1 Talbot’s paper processes were popular in British India but their use in Southeast Asia is currently unknown. Between 1844 and 1846, Talbot published the world’s first photographically illustrated book, The pencil of nature.

The book demonstrated the industrial applications of his patented positive-negative calotype process. In 1851 his efforts were made redundant by the release of the patent-free wet-collodion emulsion on a glass plate developed in England by Frederick Archer (1813–1857). The new ‘wet-plate’ process gave far superior clarity of detail and, when paired with brilliantly detailed printing papers coated in silver-sensitised albumen (egg white), provided the means for photographic images and photographers to multiply and circulate worldwide.

After the introduction of the wet plate, Talbot applied himself to experiments with photoengraving. Photographs on metal and paper, including examples of both in the new three-dimensional stereoscopic process, were prominent at The Great Exhibition in London in 1851 and at the first purely photographic international exhibition held in 1855 by the Society for Promoting Crafts and Industry in Amsterdam.

The latter included 700 daguerreotype and paper photographs by sixty-five European and American exhibitors. A taste for pictures based on photographic facts from across the world was also stimulated by the huge success of pictorial newspapers, beginning with the launch of The Illustrated London News on 8 May 1842. Economic reproduction of photographs alongside text in newspapers, journals and books was not possible until the adoption of the halftone screen process in the 1890s, but photographs had an influential ghost-life as the basis for drawn illustrations, which subtly changed the naturalistic style and variety of content of graphic art and public taste.

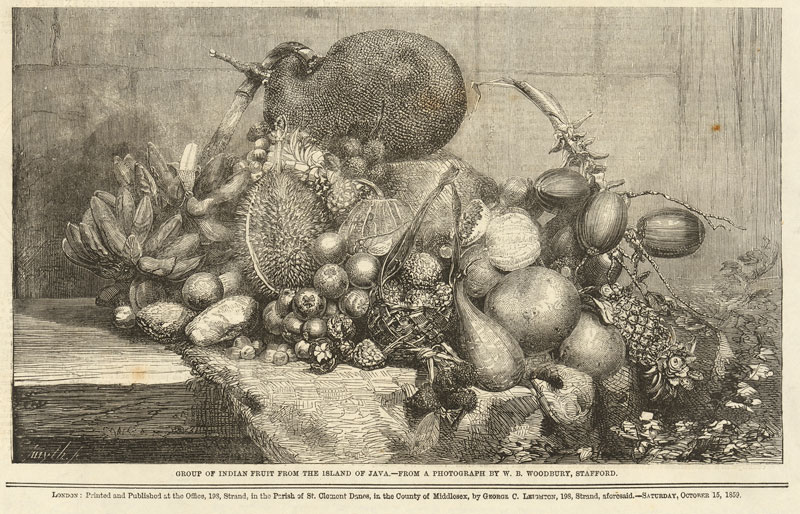

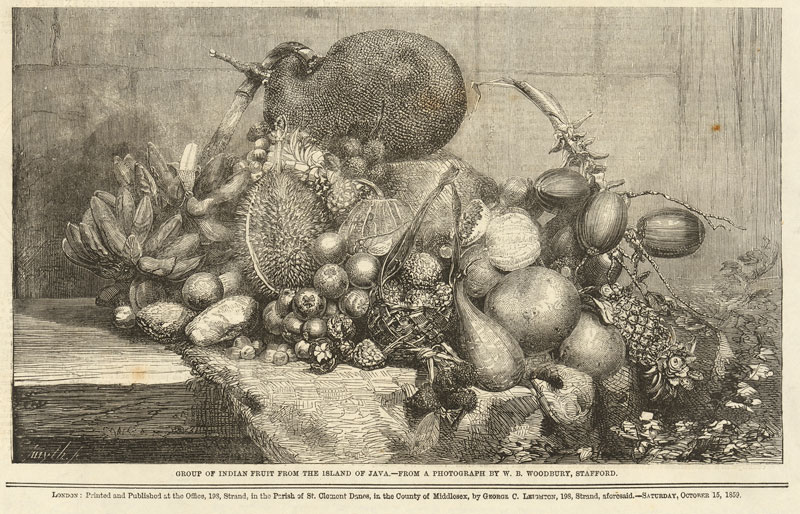

On 15 October 1859, The Illustrated London News published a half page engraving ‘from a photograph by W. B. Woodbury of Stafford’, depicting ‘Indian fruit’. This image, artistically improved by the engraver, is the earliest known published image after a photograph from Indonesia. The original was a print or stereograph on glass by British photographer Walter B Woodbury, who was, at the time, visiting London from his new studio in Java.

From the 1860s, the trickle of actual photographs and images ‘after a photograph’ became a flood, shaping the public image of Southeast Asia and how people worldwide saw themselves and the world.

Trial runs: the first photographers in Indonesia

The Ministry of Colonies in Amsterdam can be credited as the first government body to use photography to gather information. By October 1839, Amsterdam painter and art supplier Christiaan Portman (1799–1868) was exhibiting daguerreotypes in The Hague, and a translation of Daguerre’s manual and other photographic news could be found in the Nederlandsch Magazijn. The ministry equipped Jurriaan Munnich (1817–1865), a surgeon at National Hospital in Utrecht, to ‘test and employ photography in our tropical regions’ with a chief goal of photographing Borobudur, the ancient Buddhist stupa complex in Central Java.2

In Batavia (now Jakarta), members of the Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences (Bataviaasch Genootschap der Kunsten en Wetenschappen) were well-informed about the new medium and the ministry’s plan. Both the society and ministry were keen to disseminate archaeological information to enhance the international image of the Netherlands as a colonial power. Munnich made sixty-four plates of antiquities at the society’s premises, but these were deemed too poor to use.3

More exciting, perhaps, to locals in Jakarta in 1842 was the report published in the local newspaper Javasche Courant of 15 October on a new method being used to colour daguerreotype portraits in Europe. Munnich’s failure, however, led to the arrival of someone able to provide such likenesses.

Back in Amsterdam, news of Munnich’s difficulties prompted Adolph Schaefer (c 1820–1853), a struggling German-born daguerreotypist working in The Hague, to seek government support to take over his debts and equip him to work in Java and undertake the desired pictures of antiquities. Schaefer, who arrived in Jakarta in June 1844, solved the problem of tropical exposures.

The Javasche Courant of 22 February 1845 reported on his ‘beautiful and numerous’ portraits that ended the ‘despair that Daguerre’s art could ever be exercised fully’ in the tropics. However, the same paper added a warning for those unfamiliar with the new art that the results could be unflattering.4

Having shown his worth, Schaefer was commissioned in April 1845 to photograph antiquities in the collection of the Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences. By photographing the pieces outside in full sun against a plain cloth, Schaefer succeeded with sixty-six dramatic plates. He was then assigned to undertake the grandest of outdoor ‘sculptures’, Borobudur, where under much greater difficulties he successfully made fifty-eight plates of the monument. Schaefer’s estimate of the time and cost to photograph the whole site meant that no further commissions were approved.

Schaefer returned to making portraits but was unable to generate enough income to service his ministry loan. He was bankrupt by 1849 and his fate is unknown. His archaeological plates survive as a testament to his skill. None of his fine portraits are known.

Daguerreotypists were circulating like nomads throughout Australia and Southeast Asia in the 1840s and early 1850s but few could find enough customers in any one place to make it worthwhile staying for more than a few weeks. One of the more colourful characters was the upper-class Swedish adventurer and artist Cesar Duben (1819–1888) who had worked as a daguerreotypist in North and South America, China, Hong Kong and Macao, before arriving in Jakarta on 1 July 1854.

By 12 July, Duben was advertising in Java-Bode that his improved daguerreotypes were ‘durable against the climate’. He departed on 10 October 1854 to work in India and Burma and returned to Java in July 1856. A year later, he opened his Nieuwe Photographische Galerij (New Photographic Gallery) in the Hotel der Nederlanden in Jakarta.

Duben was now a ‘photographist’, and the title change may indicate he was working with the wet‑plate process. He worked in Surabaya in September and departed for Sweden from Semarang on 8 January 1858.5 Prior to his departure, Duben was photographing the family of Sultan Hamengkubuwono VI in Yogyakarta. At the sultan’s request, Duben instructed a court member in the photographic process. He also presented his camera to the sultan as a parting gift.

Like most indigenous royals in Asia, the sultan quickly realised the value of having portraits to exchange with visiting dignitaries and the distant Dutch royals. But the sultan had to wait until 1871 before one of his Javanese entourage, Kassian Céphas (1845–1912), was trained as court photographer.6

None of Duben’s work is known to survive, but his lively memoir, published in Stockholm in 1886, tells how he had realised his ‘childhood dream … to see many extraordinary countries and people’.7 The dozen lithographs after photographs sold as supplements to the memoir are all that survives of his photographic work. The work of daguerreotypists in Java similarly survives only in lithographs.

The wet-plate process on paper was in the ascendant by 1854, as was its early sideline of an attractive cased miniature on glass known as an ambrotype.8 This was evident from an advertisement by painter and photographer AAP Roeder in the Semarangsch Nieuws en Advertentieblad of 28 August that his portraits on paper did not fade and were easy to ship.9 The new was no guarantee of success: paper photographs were cheaper but had to be made in greater numbers and variety to make an equivalent income. Roeder was not heard of again.

From the early 1850s, a wide range of photographs arrived as commercial imports. Bookseller and printer HM van Dorp & Co (1853–1910) in Jakarta was one of the most active suppliers of all things photographic. The firm’s advertisement in Java-Bode on 23 September 1854 listed a treasure trove of daguerreotypes, stereoscopes, lanternslides and microscopes (no doubt a good quantity of French erotica was also sold under the counter).

The first studio of any longevity in Indonesia was that of Frenchman Antoine F Lecouteux. He began an enterprise in Jakarta in 1854 offering an extensive range of accessories such as albums and lockets for the new paper photography. On 30 May 1855, Lecouteux announced in Java-Bode that he was now associated with painter Isidore van Kinsbergen (1821–1905) and could offer a fuller range of services.

Belgian-Dutch van Kinsbergen was well known in Jakarta as an energetic lithographer, set painter, opera singer and actor. He had arrived in Jakarta in 1851 as a member of the Theatre Francais in Batavia and decided to stay on. Lecouteux sold up in 1856, while van Kinsbergen continued throughout the 1860s and 1870s. Van Kinsbergen would have noted, perhaps with some concern, the report in Java-Bode on 27 May 1857 of the arrival from Australia of photography partners Walter B Woodbury (1834–1885) and James Page (1833–1865).

Born and educated in Manchester, Woodbury had been heading for a career in engineering when he quit his apprenticeship in the Patent Office in 1852 to try his luck on the Australian goldfields. Soon after his arrival in Melbourne, Woodbury’s only discovery was that the easy pickings on the goldfields were already gone, but he was resourceful enough to manage odd jobs until finding employment with a surveyor.

As a youth Woodbury had experimented with the new wet-plate photography and a chance sighting of a camera for sale in Melbourne in 1853 led to his gaining expertise in the wet-plate process, making views of Melbourne that attracted attention and an award and ultimately led to his decision to become a photographer in 1855.

Woodbury worked in ambrotype, paper photographs and stereographs in Melbourne and the goldfields, but competition was tough even with partners.10 In Beechworth in 1857, he joined up with his latest new partner, young Page from Kent. Page had similarly experimented with the earliest wet-plate photography as a clerk in London before succumbing to gold fever in 1852.

In April 1857, the partners in the Woodbury & Page studio left for Java, arriving in June. Aboard ship, Woodbury wrote to his mother on 4 May to say their plan was a brief stop in the Dutch East Indies then onto Borneo, Manila, China, India and home.11

Woodbury’s earlier plan to do the Pacific and then settle in South America was abandoned. His first letters from Jakarta told of his delight in the tree-lined streets of the uptown suburb where foreigners lived and, best of all, there were only three photographers as competition, although he does not name them.12

By 1858 HM van Dorp & Co advertisements promoted albums for the new paper photographs as well as photographic supplies for travelling photographers and amateurs. HM van Dorp & Co continued to be active in photo publishing until the mid 20th century.

Few amateurs are known to have been working in the area at the time other than German naturalist and artist Franz Wilhelm Junghuhn (1809–1864), who recorded family life from the late 1850s, and the circle of the Holle, van den Berg, van der Hucht and Pryce families in the 1860s including Thomas Pryce (1833–1904) from Wales, who wrote a few years later on the difficulties of photography in the tropics.13

Woodbury & Page offered portraits, large and small and were well armed with cases and mounts. The studio also engaged an artist to colour its most expensive one-guinea portraits, and Woodbury soon reported home on a dream come true: ‘Every day we have had carriages at the door every ten minutes and have got engagements for the next week. You at home can have not have the faintest idea of what a lovely place this is’.14

The exceptional quality of the few surviving examples of his ambrotypes shows that Woodbury’s skill and artistry were the reasons for the studio’s success. Woodbury was also fascinated by his exotic surroundings and by the diversity of the locals and visitors that came to the studio: ‘we have an extraordinary variety of customers in this part Dutch Chinese Malay half castes, Madurese, Bandanese, Arabs countesses, chevaliers Javanese and a variety of nations’.

The partners’ first field trip was to the Dutch Governor’s palace and botanical gardens in Buitenzorg (Bogor) in September 1857; but of most interest were the monuments of Central Java and the sultan’s courts of the principalities that they planned to visit. Woodbury reported in March 1858 that he was dispatching a box of large glass views to The Illustrated London News.15

Photographic rambles: working in the tropics

Moving from one temporary branch to another in Surabaya and further afield was still essential to business survival. Field trips remained crucial throughout the existence of Woodbury & Page until 1908. By 1859, business was good enough for Woodbury to persuade his brother Henry to join him. Henry arrived in April 1859, enabling Walter to travel to England to buy supplies, sell views and do some self-promotion.

He sold a set of some forty stereoscopic views to the London photographic publishers Negretti & Zambra, who later promoted them in the British Journal of Photography in April 1861 as the first ‘to show the beauties of tropical scenery’.16 By then, the firm had already published stereoscopic views of China by Swiss photographer Pierre Rossier in 1859, among the first images of Asia widely seen in Europe.17

In England, Woodbury caught up on the new trends, one of which was an upsurge in the production and exhibition of albums of views and now that the wet-collodion process was established, making multiple copies possible.18 At the other end of the spectrum, Woodbury invested in the new miniature carte‑de-visite portrait camera and cards patented in 1854 in Paris. Woodbury & Page could now offer the economical carte-de-visite portrait to customers and began making a range of portraits of ‘native types’, indigenous aristocrats and residents of the Chinese quarter.

Woodbury’s own servants were arranged in tableaux illustrating native lifestyles. Woodbury made a second trip to Central Java in June 1860, this time with Page and brother Henry, which he curiously described the following year in the British journal The Photographic News as a ‘ramble’ by a ‘Photographic tourist’.19

Others, such as Tom Pryce, who was also a customer of Woodbury & Page in the 1860s, found photography in the tropics a little more demanding. Pryce despaired over the heat, bright light and dark foliage always in motion from slight breeze, but he was frustrated above all by the difficulties of procuring chemicals and ‘the dampness of the atmosphere, which seems to delight in damaging everything to which it has access’.20

Woodbury & Page advertised its first set of six views of Kediri, Malang and Ngantang in 1861 and a series of ‘Batavia views’ in 1863. Before this, Batavia had not been a subject of primary interest. Page and Woodbury operate separately at this time so that when the business moved into a fixed address in Jakarta, in premises formerly occupied by HM van Dorp & Co, it became the Photographisch Atelier van Walter Woodbury.

In January 1863, Woodbury married Marie Sophia Olmeijer, a beautiful teenage Dutch–Malaysian girl and the couple departed Java, signing over the business to Henry and Page. Walter set up a studio in London and had future fame as the inventor of the woodburytype, but no enduring fortune. While Page and Woodbury had had periods of disassociation in Java in 1861–62, Page was involved in early tours in Java and the development of the first suite of ‘Batavia views’ in May 1863 before he became ill from a tropical fever. He returned to England shortly before his death in 1865.21

Woodbury & Page: the brand

A Woodbury & Page print is usually immediately identifiable by its distinctive rich tone, fine detail and classic, distanced topographical perspective. The firm was attentive to its logo and many works are stamped. Woodbury’s technical expertise and establishment of a work culture and aesthetic for the studio made the brand and earned him his role as master of the atelier. Although, without Henry and, more importantly, brother Albert, who joined the business in 1864, to maintain the brand over the next decade and a half, Woodbury & Page would have slipped from view.

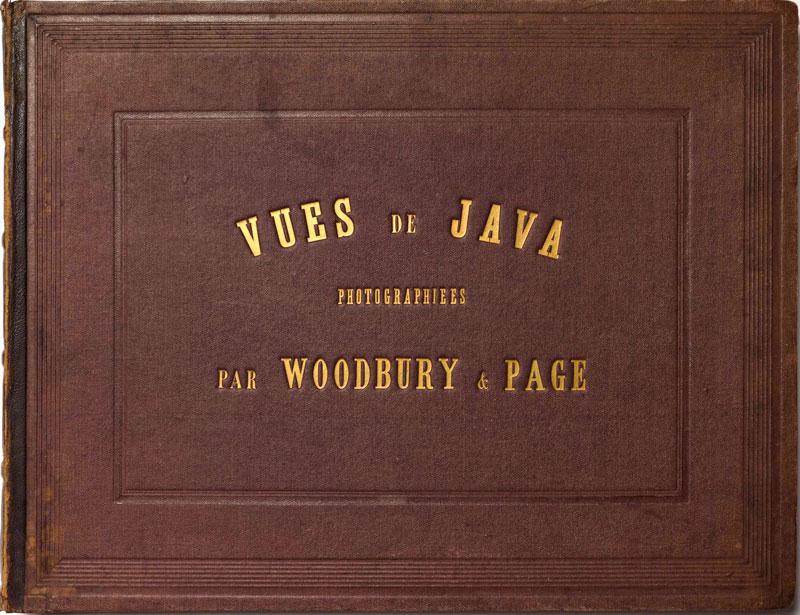

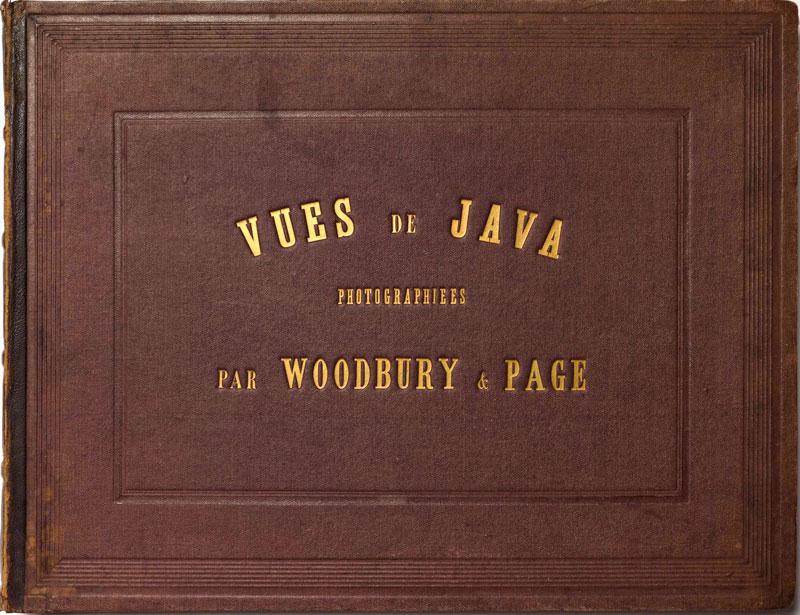

Early Woodbury & Page albums for affluent clients such as the Pryce family were in scrapbook format. By the 1870s, the firm had a standard plain-cover album, approximately forty-two centimetres high by thirty-one wide, into which customers could have a standard or personal selection of prints mounted. The cover was imprinted with titles such as ‘Vues de Java / photographies par Woodbury & Page’ because French was the language of high culture in the Netherlands.

The firm appears to be the only studio in the 1860s and 1870s to have its own album covers, which assisted in the international recognition of the brand in its own time as well as in today’s auction rooms. Within the brothers’ output for the Woodbury & Page studio, relatively few prints survive from Walter’s six years, and no work is firmly attributed to James Page or to Henry specifically, who was based as much in Surabaya as Jakarta.

From mid 1864 to 1870, Woodbury & Page was owned by German Carl Kruger, with Albert Woodbury as a major participant. Albert then bought out the firm in 1870. He had the longest association with the firm, returning to England in 1882 with his wife, having sold out to ACF Groth.

Credit for maintaining the signature style over seven hundred images from across the archipelago, as well as five hundred ‘types’ listed in a sale of inventory in Java-Bode on 19 October 1879, may suitably belong to Albert. The studio ceased to advertise in 1896, but a core inventory remained in use by German FF Busenbender, who had worked with and was the successor to Groth. In 1908, he auctioned the property, equipment and negatives.

Monumental visions

Soon after arriving in Jakarta in 1857, Woodbury had heard of the archaeological photography activities sponsored by the Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences and hoped to gain a commission. He sold the society a few prints from the Woodbury & Page excursions in Central Java but the first grand-scale project to photograph antiquities using the wet-collodion process went to van Kinsbergen, who had worked with Lecouteux’s studio until it closed in 1856.

Van Kinsbergen had continued juggling his photography with duties as an actor and set painter and as the director of the Theatre Francais from 1858 until it also closed in 1860. He remained involved in theatre in Jakarta until his death in 1905, but photography provided him with a living from 1860. His skill as a photographer was evident enough by 1862, as he was invited to join the Dutch East Indies Government mission to Bangkok that year.

On his return, van Kinsbergen joined a series of tours the residential districts in Java, Madura and Bali and the four independent royal territories, including the palaces of Susuhunan Pakubuwono IX at Surakarta, Hamengkubuwono VI at Yogyakarta in Central Java and I Gusti Ngurah Ketut Jelantik of Buleleng on Bali.

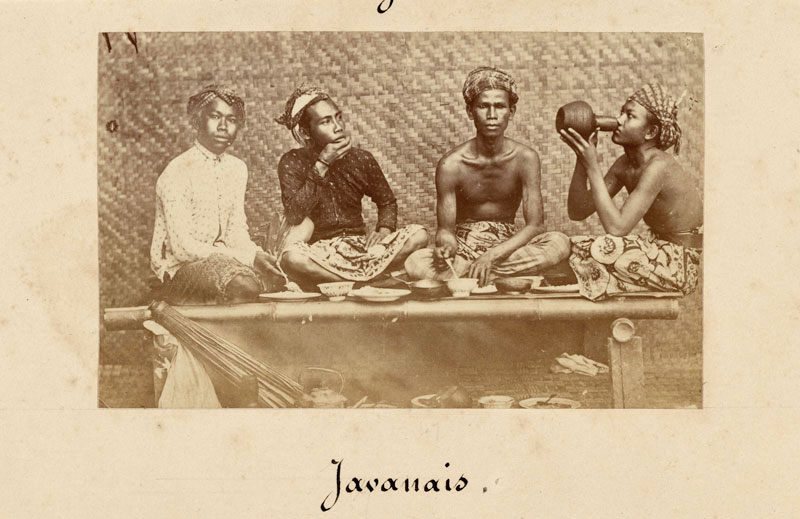

By the mid 1860s, van Kinsbergen had a repertoire of impressively baroque still-life studies as well as fine portraits and tableaux of Javanese ‘native types’ and royal portraits, often taken up close, in which the models have a strong presence as individuals.

Van Kinsbergen’s tableaux are more adeptly directed and engaging than those of Woodbury & Page and were as widely published, although usually uncredited. His image of a Malay family at home appeared in The Illustrated Australian News in 1867 and in Le Tour du Monde in 1880 in an article by photographer and explorer Désiré Charnay (1828–1915). Van Kinsbergen’s Javanese children was particularly popular.22

Despite only a few photographers operating in Jakarta, there was no lack of images. French traveller Count Ludovic de Beauvoir reported being besieged by Chinese and Malays trying to sell him ‘photographs from Paris’ on the veranda of his hotel in Jakarta in 1866. He was also given royal portrait photographs at the Surakarta palace, including one by van Kinsbergen that he reproduced in his frequently reprinted 1869 travel book Java, Siam, Canton: voyage autour du monde (Java, Siam, Canton: travel around the world).

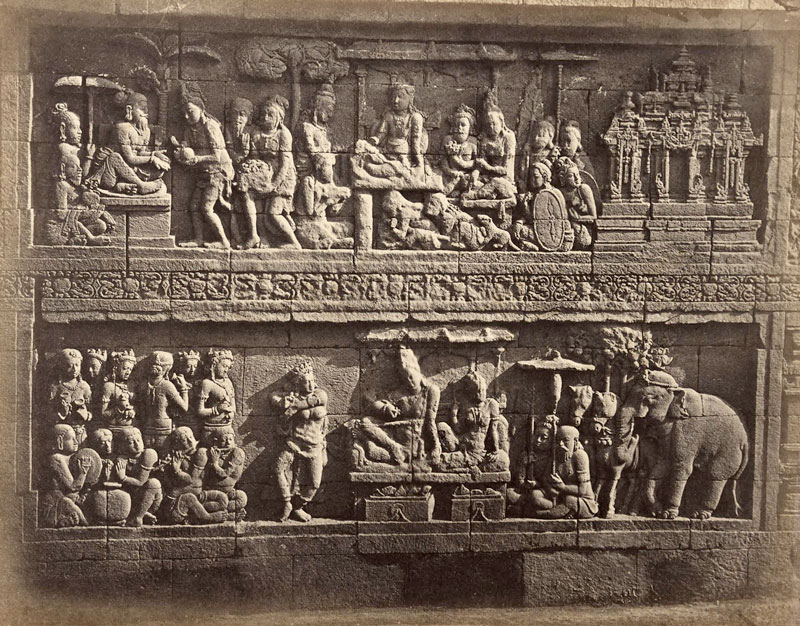

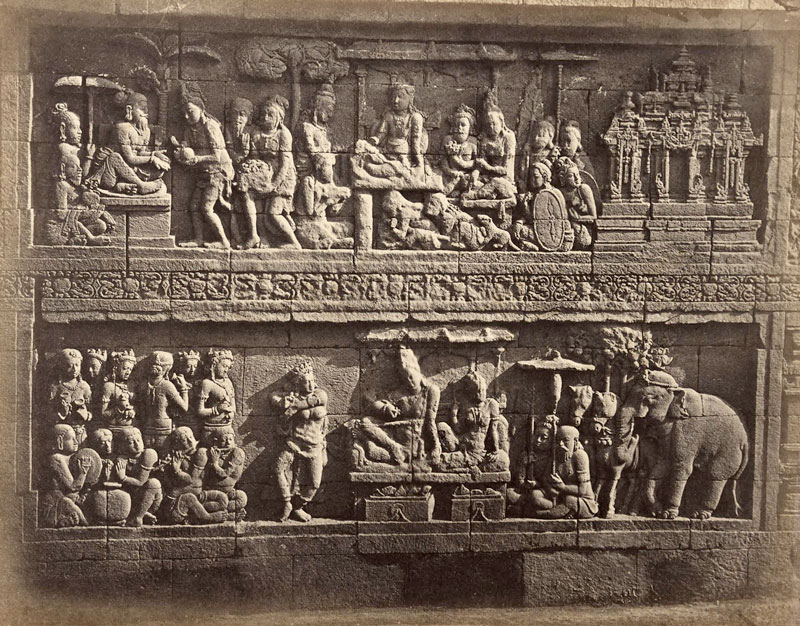

What would bring van Kinsbergen his greatest fame, however, was a commission in 1862 from the Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences to photograph the recently restored Borobudur. He was initially guided by Reverend JFG Brumund, a local specialist in Javanese antiquities, but Brumund died in 1863, which left van Kinsbergen to his own approaches. He quickly became ardent about archaeology and, while photographing at Candi Panataran in East Java in 1867, he expressed his newfound enthusiasm in a letter to a friend: ‘when I see a treasure lying in the ground for archaeology and for photography I can’t put up any resistance’.23

To capture the spirit of sculptures at Candi Panataran, van Kinsbergen worked in direct sunlight, which created dramatic contrast in his images. The style displeased scholars but enraptured others. For more drama, he scratched away the backgrounds so that, when printed, the pieces were set off against a plain black backdrop. Van Kinsbergen had difficulties delivering the huge numbers of prints the Batavian Society needed for itself and overseas institutions.

The society was finally able to publish a folio of 341 plates titled Oudheden van Java (Antiquities of Java) in1872 and a folio of forty plates on Borobudur in 1874. A dozen or so presentation sets were made of both.

Van Kinsbergen’s major archaeological commissions were over by the late 1870s. The antiquities folios earned a gold medal at the Vienna International Exhibition in 1873 and were widely displayed over the next decade, including at the International and Colonial Exhibition Colonial Exhibition in Amsterdam in 1883. The Dutch exhibition in 1883 was where artist Paul Gauguin saw and obtained prints of Borobodur and where ethnographic researcher and collector Prince Roland Bonaparte gathered several hundred for his collection (later deposited in the Société de Géographie in Paris).24

As van Kinsbergen did not own his negatives, he could not publish under his own name. He also felt he lacked the literary skills, so he could not follow the example set by Scottish pioneer-publisher of travel photo books John Thomson (1887–1921), even if he had wished to do so. Van Kinsbergen’s dramatisation of the monuments and his techniques of using sunlight as a theatrical spotlight and blacking our backgrounds came from his love of the subject. He set the model for the twentieth-century specialist architectural photographer. With few signed prints, however, van Kinsbergen disappeared from view until the late twentieth century, when his reputation (like that of the monuments he worked on) was restored by a major exhibition and monograph in Amsterdam in 2005.25

The first indigenous Indonesian professional studio

Although van Kinsbergen and Woodbury & Page seem to have been the most esteemed and prolific studios in the mid 1870s, at least a half dozen others were at work in the port cities of Jakarta, Surabaya and Semarang before 1880.26 One of the first to appear in the Yogyakarta Sultanate was also the first known Indonesian photographer, Kassian Céphas. He was born in Yogyakarta in 1845 and, as a youth, was among the Javanese mentored by lay Protestant evangelist Christina Philips-Steven’s Javanese Christian Church in Purworejo, outside.27

In 1860, Kassian was one of the first converts to be baptised, taking the Biblical name of Peter. He married a fellow Javanese Christian in 1866. It appears that Céphas initially took up photography while working in a minor administrative capacity at the Yogyakarta palace of Sultan Hamengkubuwono VI. This was the same sultan who had sought photographic training for a court official from Cesar Duben in 1857.

The sultan had been photographed by Woodbury & Page and van Kinsbergen in the 1860s and early 1870s and was being served by Simon W Camerik (1830–1897) by 1866.28 Camerik was a Banda-born Dutch photographer based in Semarang from 1864. He provided five photographs of the earthquake in Yogyakarta in July 1867 for a small booklet published by CJ Morel, and he published views of the region and sets of portraits of the royal households.

Céphas was perhaps Camerik’s assistant on field trips as his own earliest known image is inscribed in the negative in his distinctive elegant script, ‘Baraboedoer 1872, No 70’.29 Céphas used the wet-plate process until the 1890s. By 1875, Céphas was advertising his services as ‘CÉPHAS Photographist … photographer to the Sultan’, which appeared in the De Locomotief of 9 July.

Throughout the 1870s, Céphas built up his business from a home studio in Yogyakarta. He also began an association with the sultan’s Dutch physician Isaac Groneman (1832–1912), who was a dedicated student of Javanese culture on which he published numerous articles and books. By 1884, Groneman was illustrating his early articles with photographs by Céphas.

Groneman was a founder of the Archaeological Union (Archaeologische Vereeniging) in 1885. Céphas’s first published works were sixteen collotype plates in Groneman’s elaborate folio on Javanese dance performance for Hamengkubuwono VII, In den kedaton te Jogjakarta (In the palace of Yogyakarta) published in Leiden in 1888. Groneman wished to generate interest in Javanese culture in the Netherlands and the lavish album was presented to important visitors and retiring Dutch officials.

The images for In den kedaton te Jogjakarta were of tableaux staged for the camera—although published as small plates, their richness can be best appreciated in modern enlargements.30

In 1889, the Archaeological Union began efforts to study and preserve monuments of the Hindu Buddhist civilisation in Central Java. One of the high-priority locations was the temple of Prambanan, part of the larger complex attributed in Central Javanese legend to the virgin princess Loro Jonggrang (literally ‘Slender Virgin’). Céphas was assigned to photograph the site, while his eldest son, Sem, drew the profiles and ground plans.

After delays due to the cost of using original prints, Tjandi Parambanan op Midden-Java, na de ontgraving (Candi Prambanan in Central Java, after the excavation) was published by EJ Brill in Leiden in 1893 with sixty-two collotypes. In 1890, Céphas was commissioned to photograph the one hundred and sixty reliefs on the hidden base of the Buddhist monument Borobudur. The reliefs were discovered by IW Ijzerman, president of the Archaeological Union. They were uncovered between 1890 and 1891, photographed and then reburied for the stability of the monument. The series was published thirty years later as a set of collotypes by the Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies (KITLV, Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde).

The set of 164 photographs remains the only record of the narratives on the now reburied base. It was an extraordinary partnership between Groneman, the European doctor and self-taught archaeologist and ethnographer, and Céphas, the Javanese photographer who had embraced Christianity and Masonic culture. Céphas received status and recognition for his work for Groneman, although he did not work on the doctor’s later projects, perhaps due to age. A different phase of his career followed in the last decade of his life.

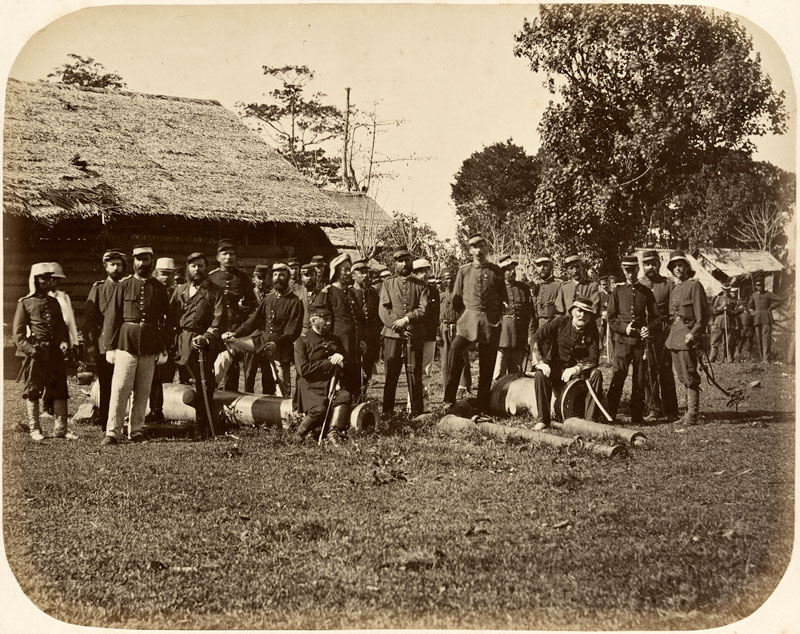

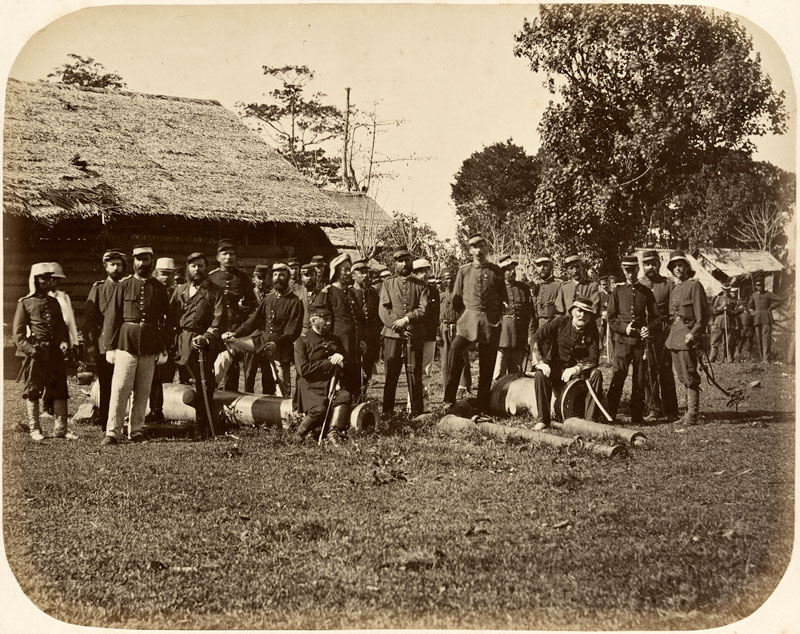

Behind the lines: military photographers

In the sixty-year period from the 1870s to the 1930s, numerous battles were fought across the Indonesian archipelago, providing the impetus for publications illustrating the colonial military, Koninklijk Nederlands-Indisch Leger (KNIL), in action in the colonies. Units of the army were dispatched to Bali, Lombok, Sulawesi, Borneo and Sumatra to incorporate them into the colonial state. While Java was under Dutch control by 1880, Sumatra remained a mysterious wilderness. In particular, the much‑desired province of Aceh and its long-standing main port Banda Aceh remained out of reach.

Aceh was a heartland of devout Muslims, and wars of resistance raged for decades. Two Aceh folios of albumen prints from the colonial topographical service, Topografische Dienst, were published by HM van Dorp & Co in 1874 to mark Dutch victories. They show troops and forts but were a little premature as the war raged on for decades.

An operator from the Woodbury & Page firm at Aceh in 1877 was also making some of the earliest images in Sumatra. A more varied and comprehensive folio of a military expedition was made by Indonesian-born Christiaan Johan Neeb (1860–1925), who was from a family of doctors. He served in a medical unit of the Dutch colonial army and documented the 1894 military expedition against the Balinese ruler of Lombok, which he published in his book Naar Lombok (To Lombok) in 1897.31

As bookplates, the images are small and not very dramatic, but a folio of large prints made by the firm of Charls & van Es & Co (1880–1940) reveal in Neeb’s photographs a livelier sense of the soldiers at work. As with all colonial wars in Asia, the often successful indigenous resistance fighters had no photographers and came to posterity in a few images of defeated former rulers on their way to exile.

Generally, reports of the many hostilities in colonial Indonesia appear distant and disengaged in comparison to the earlier war photography of Felice Beato (1832–1909) in India and China in 1858–60 and the massive published albums of the American Civil War in the 1860s.

A new generation and a new mood

The worldwide Great Depression in the 1880s may have prompted the arrival in the Dutch East Indies of a new generation of professional photographers from Europe, some also moving due to the increased competition as photographic equipment became cheaper and easier to use. Herman Salzwedel, who had worked out of van Kinsbergen’s studio in Jakarta in 1878–79, soon set up in the busy Indonesian port Surabaya and then in Shanghai from 1884 until 1893.

Salzwedel most likely worked with the new dry plates that had become available. Pre-prepared and more sensitive to a range of tones as well as requiring shorter exposures, dry plates made field work a much more pleasant activity, rather than lugging heavy wet-plate gear and volatile chemicals. In the mid to late 1880s, an interest in natural beauty appears internationally, supporting the emergence of specialists in landscape photography.

Salzwedel made very atmospheric and picturesque landscapes, even the jaunty portrait of a man at Singosari temple (likely a self-portrait) has a relaxed mood— the same prints reissued around 1900 in the cool-toned, high-gloss sharp new gelatin silver printing papers have a modern air.

Another arrival in Surabaya in 1886 via Europe and briefly Singapore was the Armenian Ohannes Kurkdjian (1851–1903). Although a political refugee and activist at heart Kurkdjian was an astute businessman. Over two decades, he established one of the largest and most successful studios in the Indonesia, eventually located in an impressive white building on a prominent corner and with some thirty staff.

Kurkdjian became known for his series of views of Java’s extraordinary volcanic region. He may have liked the outdoor expeditions in terrain not entirely unlike parts of his arid homeland. He was praised for his artistry as much as technical expertise. The Kurkdjian studio was the favoured choice for corporate and official events such as the visit of Queen Wilhelmina in 1898 for which the firm took records and presented a fine album to the Dutch Crown, after which Kurkdjian stamped all his work with the Dutch coat of arms.

From 1896, Kurkdjian was assisted by a talented young English professional photographer from Bath, George Parham (Geo P) Lewis (1875–1939). After Kurkdjian’s death in 1903, Lewis became manager and developed a picturesque aesthetic for the new tourist trade.

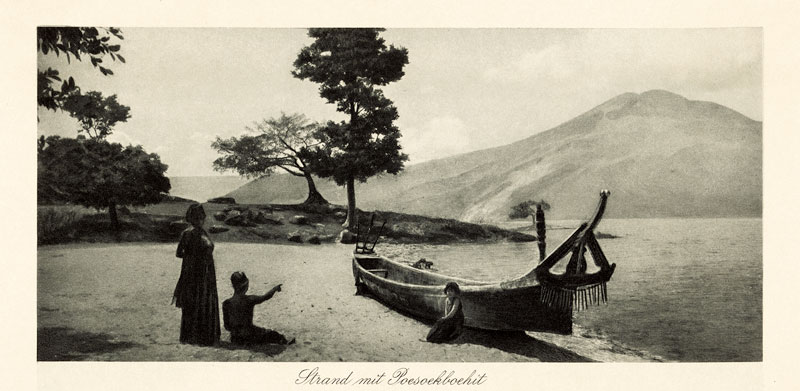

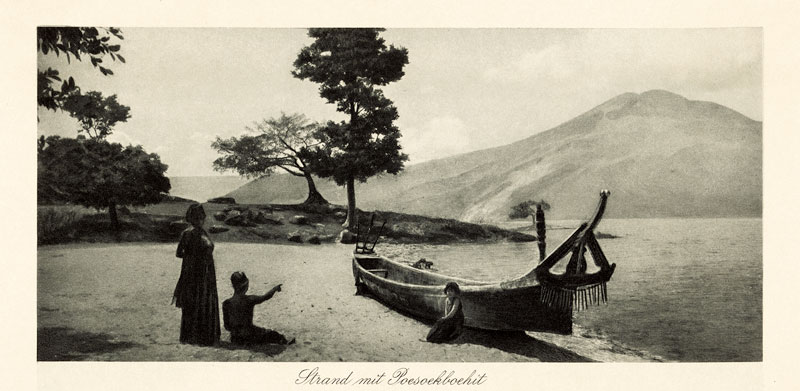

Dutch nationals made up less than half the three hundred foreign photographers at work in colonial Indonesia, but one of the most versatile and prolific was Christiaan Benjamin Nieuwenhuis (1863–1922). He was a trained musician in Amsterdam and arrived in Jakarta in 1883 as part of the wind section of the Royal Military Band. He remained in the band until 1890. The following year, he opened a photography studio in Padang, the busy port of Sumatra’s rapidly developing west coast, where he married Dutch‑Indonesian Federika van Ginkel in 1893.

Up to the 1870s, Sumatra was remote and undeveloped from a Western perspective, but an influx of foreign firms (increasing from two dozen in the 1870s to over a hundred in 1905) saw massive forest clearing for new plantations of tobacco and other crops and intensive infrastructure construction. The region was catapulted into the modern era and services such as photography swiftly moved in to cater to foreign nationals, families and imported labourers. Nieuwenhuis developed an expertise in landscape work and is distinct in his fondness for elevated overviews typical of earlier topographical paintings.

He used diagonals receding to a vanishing point to capture the scale of not only the dramatic natural landscape of Sumatra but also modern engineering works. Quite in contrast is Nieuwenhuis’s use of the new dry plates and improved exposure times for more relaxed portraiture of the Batak, Minangkabau and Nias people as well as European residents.

Nieuwenhuis had a brief tour as photographer to a military expedition in Aceh in 1901 and published his own account, Expeditie naar Samalanga onder leiding van Generaal JB van Heutsz (Samalanga expedition led by General JB van Heutsz), in Amsterdam in 1901. In the same year, he was commissioned by Isaac Groneman to work at Borobudur and brought to his depiction of the monuments a rather gentle and romantic quality. Nieuwenhuis also produced publications on the tobacco industry and numerous postcards.

Germans from national communities in Penang and Singapore were also attracted to Sumatra at the turn of the century, including Gustav Richard Lambert (1846–1916) from Dresden, who had successive studios in The Hague and Singapore from 1867 until 1914. While most studios in Southeast Asia sold a few images from neighbouring countries, GR Lambert & Co (1867 – c 1918) came to specialise in a vast Southeast Asia–wide inventory, especially of ‘native types’ and costume studies.

The studio was also one of the first to operate on a corporate scale, with some forty employees. Before returning to Europe in 1886, Lambert’s last project was to establish branches of GR Lambert & Co in Medan and Deli in Sumatra in 1885. The branch in Deli was run by Herman Stafhell (1853 – after 1898), an established portrait photographer from Sweden.32

He joined German Carl Josef (aka Charles Joseph) Kleingrothe (working 1880s–1910s), another former Lambert employee, in opening the first studio in Medan in 1889. The partners catered to the expanding tobacco industry. Stafhell relocated to Singapore in August 1897 and Kleingrothe continued on his own, reissuing earlier images around 1905 in a series of large gravure folios. He was unusual in including a folio on the Federated Malay Peninsula in 1907, when few Indonesian studios went beyond the Indies archipelago.

What had started with an engraving after a photograph of a bunch of exotic Indian fruit in The Illustrated London News in 1859 had become an encyclopedia of images by the early 1900s. But it was a one-sided one. Foreign photographers had dominated with information rather than an appreciation of the land and its peoples. Over the next half century, however, modern photography would create a more diverse and intimate image of Indonesia’s tanah air kita (our homeland).

Introduction and the Table of Contents

Footnotes

- Jules Itier travelled along the coast of Borneo but did not land there. Gilles Massot, personal communication with author, from Massot’s research project on Jules Itier’s itinerary, 2013.

- From Ministry of Colonies archives, Amsterdam, quoted in Steve Wachlin, ‘Indonesia (Netherlands, East Indies)’, Encyclopedia of nineteenth-century photography, vol 2, Routledge, New York, 2008, p 739.

- For Munnich and archaeology, see Paulus Bijl, ‘Old, eternal, and future light in the Dutch East Indies: colonial photographs and the history of the globe’, in A Erll and A Rigney (eds), Mediation, remediation, and the dynamics of cultural memory, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin & New York, 2009, pp 49–65.

- See Petra Notenboom, ‘Schaefer, Adolph (c 1820–1853)’, Encyclopedia of nineteenth-century photography, 2008, p 1248; and HJ Moeshart, ‘Adolph Schaefer and Borobudur’, in JL Reed (ed), Toward independence: a century of Indonesia photographed, Friends of Photography, San Francisco, 1991, pp 20–8.

- Duben was in partnership with Ludowick Saurman (c 1828 – after 1855) in the first professional studio in Shanghai in 1852. Saurman was Dutch and had also taken up the daguerreotype in America. He proceeded from China to work in Jakarta in 1853, Australia in 1854 and Singapore in 1855. See Terry Bennett, History of photography in China, 1842–1860, Bernard Quaritch, London, 2009, pp 20–7.

- For the continued role of photographic exchange among royalty, see Susie Protschky, ‘Negotiating princely status through the photographic gift: Pakualam VII’s family album for Crown Princess Juliana of the Netherlands, 1937’, Indonesia and the Malay World, vol 40, no 118, 2012, pp 298–314.

- Cesar Duben, Reseminnen fran Sodra och Norra Amerika, Asien och Afrika, CE Fritzes, Stockholm, 1886, p 186, cited in Bennett, p 25. I am also grateful to Bennett for additional translations of Duben’s memoir.

- ‘Ambrotype’ is the term for the wet-collodion process in which a unique positive image on glass was made by blacking out the emulsion side of a glass negative. It could be gilded and coloured and had the sharpness and three-dimensionality of the daguerreotype, and was similarly cased.

- The same issue carried a long article, ‘Photographie of lichtteekening op papier’ (Photography or light images on paper), in which APF de Seyff reported that the great illustrated newspapers in Europe ‘always choose photographs on paper’ for portraits of famous people.

- Walter B Woodbury, ‘Reminiscences of an Amateur Photographer’, The Amateur Photographer, 26 December 1884, pp 185–6.

- Woodbury, letter to Ellen Lloyd, 4 May 1857, in AF Elliott (ed), The Woodbury papers: letters and documents held by the Royal Photographic Society, AF Elliott, Melbourne, 1996, letter no 15.

- Woodbury, letters to Lloyd, 9 June & 2 September 1857, in AF Elliott (ed), The Woodbury papers, letter nos 15 & 16. The photographers were most likely the soon-to-depart Cesar Duben, possibly the recently closed studio of Antoine F Lecouteux and Isidore van Kinsbergen (who was still a part-time photographer).

- See Franz Wilhelm Junghuhn, Rob Nieuwenhuys & Frits Jaquet, Java’s onuitputtelijke natuur: reisverhalen, tekeningen en fotografieën, AW Sijthoff, Alphen aan den Rijn, 1980; and Norbert van den Berg & Steven Wachlin, Het album voor Mientje: een fotoalbum uit 1862 in Nederlandsch-Indie, Thoth, Bussum, 2005.

- Woodbury, letter to Lloyd, 9 June 1857, in AF Elliott (ed), The Woodbury papers, 1996, letter no 15.

- Woodbury, letter to Lloyd, 2 March 1858, in AF Elliott (ed), The Woodbury papers, letter no 17.

- See British Journal of Photography, 1 April & 15 April 1861, pp 127–8 & 156. The almost two-year delay in publishing the images came from the publisher’s decision to produce them as the highest quality transparencies using the albumen on glass process. A list of twenty-seven Molucca and forty-six Java stereographs was published in Negretti & Zambra’s Encyclopaedic Catalogue, 2nd edn, Negretti & Zambra, London, 1865.

- See Bennett, History of photography in China, 1842–1860, 2009, pp 227–9.

- John Hogarth published two folios of Dr John Murray’s (1809–1898) mammoth-plate Indian views in London in 1858 and 1859. Felice Beato (1832–1909) published views of the mutiny sites in 1858. Alongside Pierre Rossier (1829 – c 1898), these two photographers produced the most commonly seen images of Asia in these years.

- Woodbury’s article was published across three issues. Walter B Woodbury, ‘Photographic tourist: photography in Java—account of a short photographic ramble through the interior of the east end of the island’, The Photographic News, 15 & 22 February & 15 March 1861, pp 78–9 & 91–2 & 126–7.

- Thomas Pryce, ‘Photography in India’, The Photographic News, 7 & 14 October 1864, pp 484–5, 497–8.

- See Scott Merrillees, Batavia in nineteenth century photographs, Editions Didier Millet, Singapore, 2007, pp 268–9. Merrillees argues that Page, as the principal in Jakarta, was responsible for the first Batavia topographical set offered in the Java-Bode of 27 May 1863. He also notes that the quality of the set is poor and suggests that Page’s role in the signature style of the Woodbury & Page brand appears weak. Similar albums of city views and panoramas on paper were being marketed worldwide from the mid 1850s.

- For examples, see editions of Count Ludovic de Beauvoir’s best-selling travelogue Autour du monde, which began in 1868; the Dutch travel magazine Eigen Haard, which launched in 1875; and ‘Six semaines à Java par M Désiré Charnay’, Le Tour du Monde, vol 39, no 991, 1880. Désiré Charnay visited Java in 1878–79; his own collodion negatives transferred to waxed albumen paper are held at the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris.

- Isidore van Kinsbergen, letter to L Norman, 14 June 1867, quoted in Gerda Theuns-de Boer & Saskia Asser, Isidore van Kinsbergen (1821–1905): photo pioneer and theatre maker in the Dutch East Indies, KITLV Press, Leiden, Uitgeverij Aprilis, Zaltbommel, & Huis Marseille, Amsterdam, 2005, p 68. This is the definitive work on van Kinsbergen.

- Boer & Asser, Isidore van Kinsbergen (1821–1905), 2005.

- Boer & Asser, Isidore van Kinsbergen (1821–1905), 2005, n 21.

- Museum voor Volkenkunde, Toekang potret: 100 years of photography in the Dutch Indies 1839–1939, Fragment Uitgeverij, Amsterdam, & Het Museum, Rotterdam, 1989, includes a directory for some 450 photographers. Jakarta, Surabaya, Bandung, Medan and Semarang had the highest numbers of photographers (in that order), although only the first three had studios before the 1880s. European names dominate until the late 1890s, when Chinese studios appeared.

- Radin Abas Sadrach (1834–1924), another adoptee in Philips-Steven’s circle, became an influential leader of Javanese Christian Church.

- Camerik marketed a set of ‘principal native grandees’ of Surakarta, Yogyakarta and Magelang as well as some views of Prambanan in the De Locomotief of 29 August 1864. In the Java-Bode of 17 February 1866, he is listed as ‘Photograaf en Kunstschilder’ (Painter and Photographer) to the Sultan.

- A 1912 obituary refers to Céphas learning from Camerik. See Gerrit Knaap, Cephas, Yogyakarta: photography in the service of the sultan, KITLV Press, Leiden, 1999.

- In full, In den kedaton te Jogjakarta: oepatjara, ampilan en tooneeldansen, EJ Brill, Leiden, 1888. In keeping with the technological advances of photography, Céphas bought a new camera in 1886 that could capture pictures in 1/400th of a second.

- CJ Neeb, Naar Lombok, Fuhri, Surabaya, 1897. CJ Neeb was a half-brother of Dr HM Neeb, who was famous for his documentation of the dead Acehnese in the Aceh campaign; see Anneke Groeneveld, ‘HM Neeb: a witness of the Aceh War’, Toward independence, 1991, pp 72–7; and Jean Gelman Taylor, ‘Aceh histories in the KITLV Images Archive’, in RM Feener, P Daly & A Reid (eds), Mapping the Acehnese past, KITLV Press, Leiden, 2011, pp 199–239.

- See John Falconer, A vision of the past: a history of early photography in Singapore and Malaya—the photographs of GR Lambert & Co, 1880–1910, Times Editions, Singapore, 1995 (1987); and Ian Charles Sumner, ‘Lambert & Co, GR (1867–1918)’, Encyclopedia of nineteenth-century photography, 2008, pp 815–6.

Click here for the Introduction & the Table of Contents

Images for this essay

|

#GN 1-2: Walter B Woodbury (after) Group of Indian fruit from the island of Java 1858,

woodcut in The Illustrated London News, 15 October 1859 |

| |

|

| #GN 1-3: Woodbury & Page Indian fruit c 1858, carte de visite |

| |

|

| #GN 1-4: Woodbury & Page Batavia roadstead c 1865 |

| |

|

| #GN 1-5: Woodbury & Page Javanese fruit seller c 1863, carte de visite |

| |

|

#GN 1-6: Adolph Schaefer Sculpture of Hindu god Karttikeya 1845,

daguerreotype, courtesy Leiden University Library |

|

| |

|

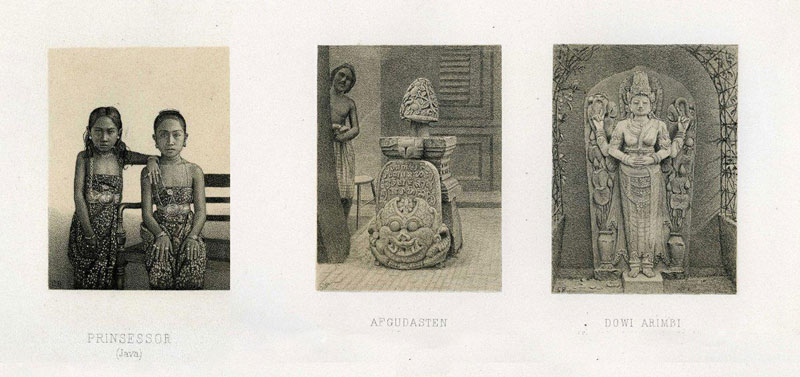

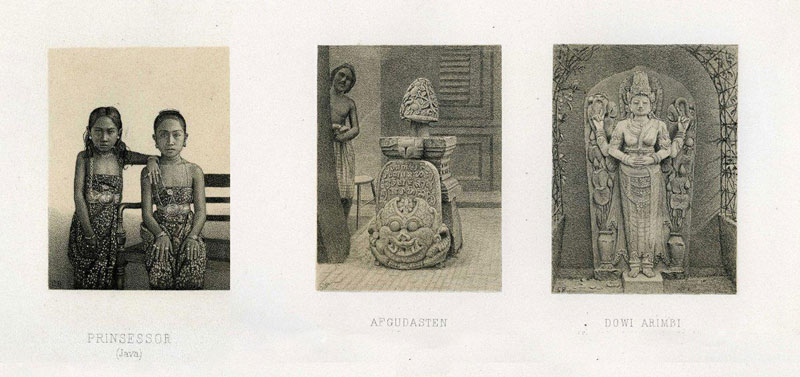

| #GN 1-7: Cesar Duben Princesses and Antiquities 1857, photolithographs from supplement to his Minnen fran Java 1886 |

| |

|

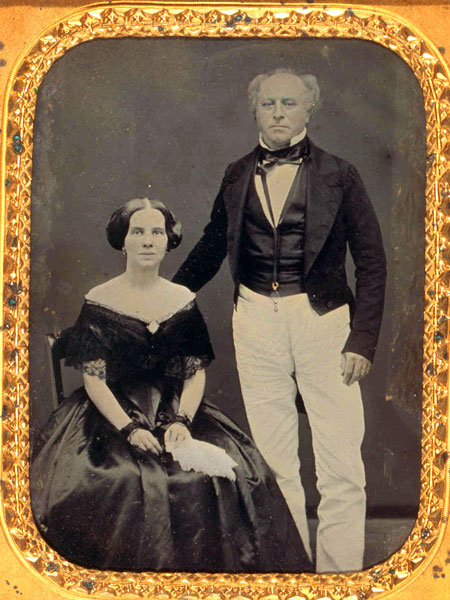

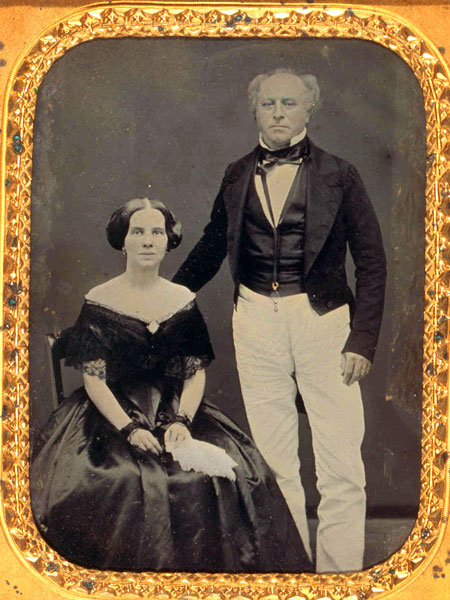

#GN 1-8: Woodbury & Page

Ernst Willem Cramerus and his wife Ambroisine Marie van Son 1857,

ambrotype, courtesy Leiden University Library |

|

| |

|

| #GN 1-9: Woodbury & Page River in Chinese camp 1859, Negretti & Zambra stereograph, courtesy Wim van Keulen |

| |

|

| #GN 1-10: Woodbury & Page Khouw family residence, Jakarta c 1870 in Vues de Java assembled 1880 |

| |

|

| #GN 1-11: Woodbury & Page Java. Borobudur 1866 |

| |

|

| #GN 1-12: Woodbury & Page Vues de Java assembled 1880 |

| |

|

| #GN 1-13: Woodbury & Page Anai Valley, West Sumatra c 1875 |

| |

|

| #GN 1-14: Isidore van Kinsbergen Javanese fruit c 1865 |

|

| |

|

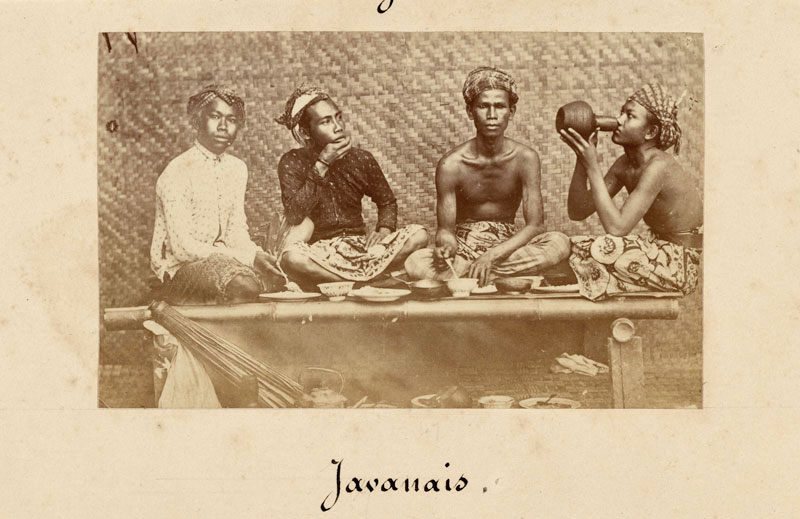

| #GN 1-15: Isidore van Kinsbergen Javanese c 1864, carte de visite |

| |

|

| #GN 1-16: Isidore van Kinsbergen Bas relief at Borobudur 1873 |

| |

|

| #GN 1-17: Isidore van Kinsbergen Stupas at Borobudur 1873 |

| |

|

#GN 1-18: Kassian Céphas Deep-relief Hindu sculptures c 1891,

plate IX inTjandi Parambanan op Midden-Java, na de ontgraving 1893 |

| |

|

| #GN 1-19: Kassian Céphas Court dancers at Yogyakarta palace 1884,plate VII in In den kedaton te Jogjakarta 1888 |

| |

|

| #GN 1-20: Kassian Céphas Borobudur 1872 |

|

| |

|

| #GN 1-21: Topografische Dienst Battery of 12-cm breech-loading canons at the bivouac |

| |

|

| #GN 1-22: General staff in the palace |

| |

|

| #GN 1-23: The river battery from Vier en Dertig gezigten op Atjeh 1874 |

| |

|

| #GN 1-24: Charles J Kleingrothe, Beach with view of Mount Pusuk Buhit, from his Sumatra’s OK c 1905 edition |

Return to Introduction and the Table of Contents

|