|

Travels with Indonesian Photography

This is a revised version of my 2022 essay published in Brian C. Arnold (Ed). The History of Photography in Indonesia, from the colonial era to the digital age, Amsterdam University Press.

National Gallery of Australia (NGA) in Canberra has a very significant holding of photographs from the Dutch East Indies. This essay looks at some of my research and stories behind the building of that collection.

Please note that the small selection of photographs on this page have abreviated captions. There are more detailed captions and all the photographs from the original essay on the linked Plates Page

Essay by Gael Newton AM

(revised and uploaded August 2025)

| My Asia-Pacific photography adventure began in 2005 when Ron Radford, Director at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) in Canberra where I was the Senior Photography Curator, enthusiastically endorsed my exhibition proposal for an ‘other world’ history of photography surveying the first century of photography across the Asia-Pacific region.

Radford’s vision was to re-center the collecting policy of the NGA to better reflect its position in the Asia-Pacific in general and Southeast Asia in particular.

The Gallery already held one of the finest collections of Southeast Asian textiles but had no collection of Asia-Pacific per se and most notably lacking was photographs from Southeast Asia. |

|

|

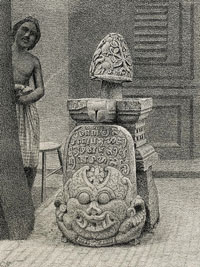

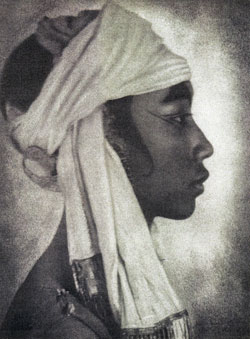

#A03: Young maidens at a sacrificial feast,

Thilly Weissenborn |

|

The idea for a survey of the first century of medium’s history outside the axis of London, Paris and New York had begun in 1998 when Raimy Che Ross, an intern from the Australian National University art history program, pointed out how few Asian photographers were represented in the NGA’s photographic collection. The reality was that relatively few photographs of Asia were held by the Gallery.

The NGA held treasures such as nineteenth-century photographs by Felice Beato in India and China along with a number of prints by Japanese contemporary photographers. Over the next decade the Gallery acquired a small group of works by Asian photographers past and present and images of Asia by iconic foreign travelers such as Henri Cartier-Bresson and Ernst Haas (color images of Balinese dancers).

Finding work by Asian photographers, either past or contemporary other than from Japan, was hampered by the fact that only a few of the Euro-America dealers I had dealt with held any suitable works. Paths for dealing directly with dealers in Asia, if they existed for photography, were few and remained so throughout the project.

New relationships were established with several new galleries or dealers in Euro-America as well as in India and Japan. Throughout the project, the global visibility of contemporary Asian photomedia artists rapidly escalated but that area was outside the scope of the project.

On Boxing Day 2006 I pinned a map of the Asia-Pacific to my wall and sat down at my home computer in Canberra to start searching out actual photographs, contacts and websites. That is how the rich and comprehensive colonial Indonesian books and photographs collection of Dutch rare book and print dealer and scholar, Leo Haks, were first located and eventually acquired in 2007. The Haks collection was compiled mostly from within Europe. A catalog and archive of some 4,000 prints and over 100 books and magazines in this collection is now available on the NGA website collection search and Research Library catalogue. At the time of writing, the Haks collection of Dutch family albums from Indonesia is not catalogued.

Material for the NGA’s Asia-Pacific collection ultimately came from dealers across the world, often found on eBay. I made several overseas trips but largely googled my way around and built relationships with scholars, collectors and curators with expertise with similar interests. Ultimately, it is my hope that researchers looking at Asia will find their way to the NGA’s Indonesian photographs collection and make use of the incredible history and resources held in the collection.

By late 2014 when I retired from the NGA, some 10,000 Asia-Pacific photographs had been acquired and two very large exhibitions mounted; Picture Paradise: Asia-Pacific Photography 1840s-1940s in 2008 and Garden of the East: photography in Indonesia 1850s-1940s in 2014.

A seminar, Facing Asia Histories and Legacies of Asian Studio Portraiture, was held in association with the Australian National University in August 2010. The next symposium, Borohudur to Bali: Past and Present Photographic Art in Indonesia, was held in June 2014, in conjunction with the exhibition I organized, Garden of the East. This symposium brought together writers, artists, and curators from Indonesia, Europe and the United States, including some of the writers here, as well the American photographer/musician/curator/author, Brian Arnold.

Subsequent small collection shows at the NGA showed aspects of the collection, including video and print work by contemporary Indonesian artist FX Harsono. Interns played a significant role in the development of the collection and exhibitions at the NGA.

Looking back at The Garden of the East exhibition and the Indonesian collection, I decided for this essay to be partisan and comment on a favorite dozen or so images and issues over the time that sum up the experience, and reflect on my research paths since retirement.

The first photographers in the 1840s–1950s were foreign adventurers and opportunists seeking to make their fortune in Asia by introducing portrait services to far distant lands. I was enchanted by the adventures of one of the earliest daguerreotypists in Asia, Cesar von Düben. He was an aristocrat from Stockholm who in the 1840s-1950s had a decade-long escape from his responsibilities at home. He worked his way through various jobs in North and South America, China, Hong Kong, Macao, Java, India and Burma and lastly as a daguerreotype photographer in Asia, having learned the process in America. -» G5

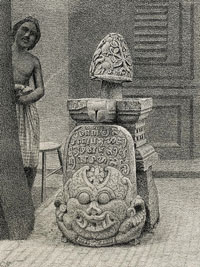

In 1886, two years before he died in Stockholm, Cesar Düben published a small memoir of his travels with photolithographic plates drawn after his daguerreotypes. Among the latter is his charming portrait of two Javanese princesses and a smiling young man peeping round a stone sculpture smiling as the photographer as he concentrated on recording a Javanese antiquity. The young girls in relatively relaxed poses look straight to camera.

Despite the translation as lithographs the moment of exposure is vivid over a century and a half later. These are some of the earliest photographic portraits of Indonesian people.

Other early portraits of Javanese were taken from 1857 by the English team of wet-plate photographers Walter Woodbury & Charles Page. They first operated in Australia in the mid to late 1850s before landing in Jakarta in 1857 and deciding the opportunities were so good that they stayed on. Woodbury was a child of the photographic age and a master of processes. In the late 1850s, he made stereographs and superb hand coloured lantern slides of Javanese court performers that were some of the first images of Southeast Asia seen in Europe. |

|

|

#A06: Princessor (Java), Cesar Diiben, lithographs, c. 1857 |

|

#A08: Woodbury & Page, glass lantern slide

|

|

A notable feature of photography in South and Southeast Asia was the interest royal courts took in portrait photography from the 1850s. Remarkably a pair of large glass ambrotypes portraits of Hamengkubuwono VI and his wife circa1858, survive in their original Woodbury & Page frames. Unique to the wet-plate process, the positive image on glass process has a three-dimensional presence.

Woodbury & Page became the most prolific of the pioneer studios in Indonesia from the late 1850s to the mid 1880s producing the first diverse large body of images to circulate internationally. Woodbury appreciated the beauty of the landscape and developed a house-style of finely detailed, richly toned, small scale prints that successive managers of the studio maintained over two decades. A quite remarkable effort.

Woodbury & Page, and later the operatives for GR Lambert & Co in Singapore, covered remote areas of Indonesia from the 1880s–1890s. Few viewers in Euro-America would have had any idea of the hard work and arduous travels of early photographers to secure views of the tiny islands from which their spices came. Sold in huge numbers, Woodbury & Page studio prints remain in significant numbers but their negatives, as with really all the early photographic firms, are now gone.

There were a number of photographers at work in Indonesia whose finesse and elegance equaled that of their better-known Euro-American contemporaries. Long term residents such as the flamboyant Dutch-Flemish theatre director, the archaeological photographer Isidore van Kinsbergen in Jakarta and the Dutch C.B. [Christiaan Benjamin] Nieuwenhuis in Sumatra bring a warmer and more appreciative eye to their work.

Dane Kristin Feilberg made astonishing, fine, large views of the Batak of Sumatra, the equal of those of the iconic photographers of the American West. Germans Herman Salzwedel (a personal favorite) made the most lyrical landscapes.

Carl Kleingrothe documented the Indonesian archipelago and Malayasia in mass-produced print portfolios of considerable charm and now of historical significance. |

|

|

#A14: C. Nieuwenhuis |

|

The wars against the native people in Atjeh (now more commonly titled, Aceh) resulted in ambitious portfolios in the 1870s produced by the Dutch Topografische Dienst van Nederlands Indie (Topographic Service). Even if celebrating battles that were rarely conclusive victories, the portfolios are early documents of guerrilla warfare, reminiscent of the remarkable work by Timothy O’Sullivan and Alexander Gardner during the American Civil War.

In making my way through the thousands of images of the Haks collection, Muslim life in The Dutch East Indies appeared to have been of minor interest to colonial era photographers. However, Dr. C. (Christiaan) Snouck Hurgronje’s publication of photographic portraits of men from Indonesia making the Haj circa1889 is precious given the lack of other documentation.

Family album photography forms a large part of the archive of the Indonesian collection and the genre was well represented in Garden of the East exhibition and catalogue. I was indebted to Australian scholars Susie Protschky and Indonesian-Australian artist Lushun Tan for their revelation of how interesting that material was. My time at the NGA was too short after the 2014 exhibition to do more research on the albums.

The NGA archive includes over one hundred and fifty albums mostly from the estates of families who returned to the Netherlands in the post war years. It is hoped these will form a resource in our region for future study. Few of the albums appear to have been be compiled by Indonesian families but many show the multiracial composition of middle-class Dutch families.

An issue that was significant my research was the elusive history of locally born photographers. In the directory of over 400 photo studios in the Dutch East Indies from 1850-1940 compiled by Dutch photo historian Steven Wachlin over years of research up to November 1988, there are some 315 European, 186 Chinese, 45 Japanese, and 4 ethnic Indonesian photographers.

The latter were Kassian Cephas in Yogyakarta, A. Mohamad in Jakarta, Sarto in Semarang and P. Najoan active on Ambon 1895-1915.

Kassian Cephas in Yogyakarta is the first known Indonesian professional photographer. His career began in 1872 under tutelage from Banda-born Dutch professional S.W. Camerik, a court photographer to the Sultan of Yogyakarta in the late 1860s-early 70s. This is a role that Cephas assumed circa 1875 until his own retirement in 1910. |

|

|

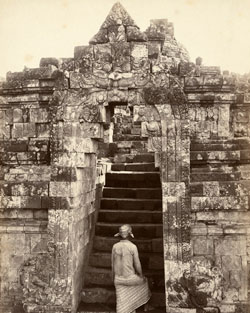

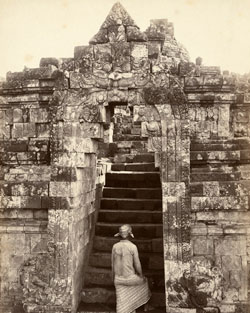

| #A18: Man climbing the front entrance to Borobudur, Kassian Cephas 1872. |

|

Cephas worked closely with Dutch physician Dr Isaac Groneman on the photography of Javanese antiquities from the mid 1880s-1890s. In recognition of his work, he was awarded equal status by the Dutch Government. Cephas is remarkable for his seemingly fluid movement between Dutch and Javanese society.

While successful as a court and commercial photographer throughout the late 19th and early 20th century, Cephas did not have the scale of operation or fame of his contemporary Raja Deen Dayal in India or the various well-known 19th– early 20th century Japanese photographers in the Treaty ports.

I have written a number of articles and papers in support for the case that his life and work is that of a major international figure. Cephas’s persistent self-portraiture within a large group of his commercial images was not in my view incidental, nor just an attempt to illustrate the scale of the subjects represented in his pictures.

This action was political in asserting his relationship to antiquity while being a modern image-maker.

Cephas and son Semuel’s series of lovely ladies for postcards at the turn of the century have none of the sleaze of other examples of this type of souvenir production. It is telling that the Malay language Bintang Hinda [Indies Star] journal, published in the early 20th century in Amsterdam but promoting new attitudes to the education and role of Indonesians, chose to use one of these dignified and graceful portraits of Javanese dancers on their promotional material. |

|

|

#20: Javaansche schooner Native beauty, Cephas c. 1909. |

|

Kassian Cephas has been the subject of a monograph and a number of commentaries and articles but is deserving of further research including in his relationship with the Javanese Christian church movement. Similarly, work is needed on the ethnic mix of local photographers and their customers in Indonesia. American scholar Karen Strassler’s 2010 study Refracted Vision: Popular Photography and National Modernity in Java provides a picture of the role of both pioneer professional and amateur Chinese photographers, such as the brothers Tan Gwat Bing and Tan Bie Le, who published postcards in the early 20th century. Chinese and Peranakan studios have a distinct role by number and influence in Indonesia past and present, and have been the subject of different collections and studies in recent years.

Nothing has come to light about the ethnic photographers cited by Steven Wachlin, A. Mohamad and Sarto. More has been revealed recently about Johannes Paulus Simon Najoan (usually referred to as P. Najoan). Najoan was a Minahasan from North Sulawesi. He was a drawing master at the Osvia Ambon Kweekschool voor Inlandsche Onderwijzers [teachers training college for Indonesian students] from October 1885 and also taught in the Opleiding School Voor Inlandshe Ambtenaren (OSVIA) training school for Inlandsche officials in Makassar.

From an old Christian family on Ambon, Najoan showed promise as an artist when he was young and was sponsored to train for two years in Jakarta with Java born Dutch painter WCC Bleckmann in 1883-84 at The Gynasium Willhelm III. In 1884 Najon won a silver medal at the Batavia Exhibition that drew a comment in the Semarang newspaper De Locomotief of 22 October: “Mr. P. Najoan in Gang Kwitang at Batavia makes very beautiful portraits drawn in chalk after ordinary photographs.”

Some of Najoan’s photographs were collected by retired Dutch pharmacist Dr. H.F. Tillema in the 1920s for a study of the Indies. A photograph exists showing Najoan at work recording the 1898 earthquake on Ambon. A number of his images are in the KITLV collection now held at Leiden University and prints and postcards are in the Nederlands Fotomuseum in Rotterdam and several are in the NGA’s Haks collection. Like Cephas, Najoan was Christian and granted equal status with Dutch residents in 1895. He died in 1926.

The role of Japanese studios in Indonesia has yet to receive much attention. My scrutiny of the Wachlin directory suggests that more than 70 names could be Japanese. None of the listed names appear in the 19th century and in the 20th century only few most around 1910.

K. Okujo was in Sumatra in 1905-1910 and later Surakarta in 1925-30. Fukui Japanische Fotograf was in Medan from 1910-1915. M Kuriharaha of ‘Mikado’ photo studio was in Kisaran, Sumatra from 1915-35. The majority of studios operated in the 1920s and 1930s. A number had studio names referencing their ethnicity perhaps as a sign of the Japanese technical modernity just as some studios in the late 19th century co-opted the term ‘American’ to show they were up to the latest developments.

However, suspicions were held abroad at the Japanese presence. Lord Northcliffe in London in 1922 was quoted in De Sumatra Post of 25 July as saying that, “the Japanese are the Germans of the East – always working, propagating, penetrating, spying throughout the world, noting as well that the Japanese photographer was ‘everywhere in Asia’.”

Photography was well advanced in Japan, and amateurs as well as professionals in Indonesia would have been kept up to date in their equipment and style though Japanese camera magazines.

The influence of the Japanese photographers as a source for cameras and aesthetic ideas across Asia in the post war years was significant. The stories behind expatriate Japanese photographers have yet to be fully explored.

Almost nothing is currently known of the personal lives and careers of Chinese or Japanese photographers in Indonesia. Two Japanese, S. Satake and K.T. Satake, have attracted significant attention. They were apparently both owner/photographers of Tosari Studio in in the volcanic Tengger mountains of East Java, a popular tourist resort in the 1920s. |

|

|

#32: Women on Road in Bali, K. Satake c. 1928. |

|

The De Indische Courant of 24 November 1931 described K.T. Satake as the well-known photographer and tourist shop owner-photographer in Tosari. They describe him as an artist in this field.

‘Just as he seeks out the beauty of the Javanese landscape and thereby lets himself be put off by no effort, so do very few. He makes distant trips through the country around Tosari and captures the most beautiful places and the most beautiful moments, and so one can find pictures with him, that one sees nowhere, because hardly anyone enters the places, where he comes. Satake is now going to undertake a big trip through Sumatra, to capture a lot of beauty on the sensitive plate. He has made a large caravan, which is now ready and has already proven to meet the requirements.’

On 12 February 1936, the Soerabaijasch Handelsblad reported on Satake as a Tosari resident of 15 years who had published a book of his work on Java, Bali and Sumatra, printed under his own supervision in London. This was a lavish tome in Dutch and English titled Camera-beelden van Sumatra, Java & Bali [Camera pictures of Sumatra, Java & Bali], published in Surabaya in 1935. The book had black and white but also rare color plates made using the French autochrome process.

This beautiful book is unprecedented in size, scope and quality, and is a remarkable example of a modern photobook from Southeast Asia. Quite what relationship K.T. Satake had to the many prints from the 1920s stamped as by ‘S. Satake’ ‘Tosari studio’ is not clear but the latter’s moody scenes are finely detailed and subtle in tone and with a Japanese aesthetic.

Alongside Satake in Tosari is an equally fine and even more prolific photographer, Thilly Weissenborn. Her luminous prints share an artistic style with Satake, perhaps reminiscent of the pictorialist style found around Europe and the United States in the early 20th century. Indonesian born of naturalized Dutch-German parents, Weissenborn is the only known woman professional in colonial Indonesia. She employed Indonesian girls as assistants but none are known to have operated their own studios.

Weissenborn first worked for the lavish Surabaya studio founded by Armenian Ohannes Kurkdjian in the late 19th century. She worked under British manager George P. Lewis until his return to Britain during WWI. Lewis produced numerous large prints of beautiful landscapes in a naturalistic art salon style presenting a bucolic imagery of a rural paradise livened up by belching volcanoes.

The lavishness of their operation can be seen in pictures of the palatial Kurkdjian studio and in the scene of Weissenborn and Lewis retouching the enlarged portraits available to affluent Surabayans. Very few portrait prints of this scale have survived.

In 1917 Weissenborn went to Garut in West Java to manage the photo service of the pharmacy of Dr Denis G. Mulder, also active as an x-ray pioneer. After Mulder left in 1920, Weissenborn reformed the business as Foto Lux and worked there until her internment during World War II. Her negatives were destroyed in the aftermath of the war.

The monograph published in Amsterdam in 1983 on Weissenborn was written by Ernst Drissen. This was titled Vastgelegd voor Later Indische Foto’s (1917-1942) van Thilly Weissenborn [Retrospective. East Indian Pictures (1917- 1942) of Thilly Weissenborn]. Weissenborn has not had the international attention her very fine work deserves.

There is little mention in the few histories of colonial Indonesian photography of the photographic societies of amateur photographers. American scholar Karen Strassler’s Refracted Visions: Popular Photography and National Modernity in Java includes a valuable account of early photographic societies.

Dutch curator Flip Bool’s 1979 Fotografie in Nederland 1920-1940 provides precious biographic entries on some of the Dutch photographers working in Indonesia in the 1930s-1940s. They include Dr Mulder and Professor E.J. G. Schermerhorn, a chemical engineer who taught photography at Technische Hogeschool, now the Institut Teknologi Bandung.

Professor Schermerhorn was an expert in bromoil printing, perhaps the most demanding process favored by the pictorialist photographers in the West. This process gave a flat graphic tone and contrast to photographic prints perhaps suggestive of printmaking more than photography.

In February 1924, with other Dutch residents, Schermerhorn founded the first photography club in Indonesia, the Perhimpunan Amatir Foto – PAF (then Preanger Amateur Fotograafen Vereeniging). In 1931 he published a text on photography in the tropics and in later life in the Netherlands he turned to dramatic abstract photography. |

|

|

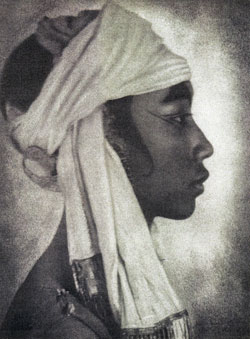

#37: Javanese Actor, Professor E.J.G (Edgar Johan Gerhard) Schermerhorn, half-tone plate LVIII in Photograms of the Year 1931. |

|

In recent years I have continued to take an interest in the role of art photography and photographic society salons and documentary photographers of 20th century Southeast Asia. Another area of interest has been vernacular Southeast Asian studio portraiture from the 1920s–1970s. There is flamboyance to the genre possibly inspired by cinema that seems unique to the region. We barely know who most of the early to mid-20th century photographers were and likewise little of the range of their clientele.

Tentative projects have begun at the National Gallery Singapore to retrieve the lost careers of post war documentary and salon photographers in Southeast Asia. Deeper studies of communities of photographers and their clients can only be done with multiracial and multilingual scholarship in Indonesia, Japan, China and the Netherlands. It will be fun to view the outcomes as photographic heritage is a shared legacy regardless of ethnicity of the photographer.

More detailed captions and more photographs available on the Plates Page

Other essays and papers by Gael Newton

|