Max Dupain - classicist

Gael Newton AM 2026

|

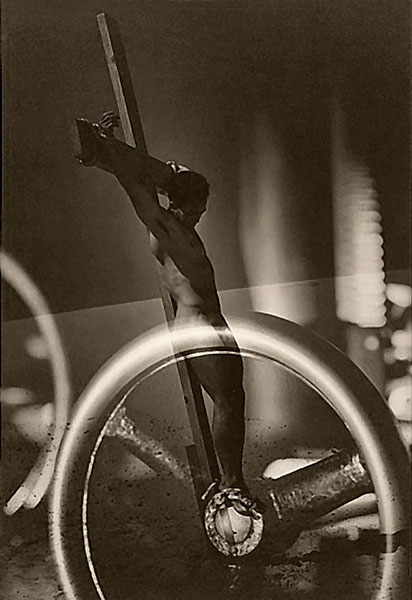

| Max Dupain: Shattered Intimacy 1936 |

A statuette of the Standing Discobolus is the centrepiece of Dupain’s 1936 surrelist still life Shattered Intimacy. This is the most poignant of Dupain’s 1930s surrealist works - indeed one of his most poetic works. In the 1990s I gave a lecture looking at the number of works Max Dupain made using two small classical Greek figurines, the male Standing Discobolus and the female Venus de Milo.

The figurines appear from 1934 through to Dupain’s service in WWII. One last work in which the head of the Venus de Milo’s lolls in the tide at surf’s edge dates to 1975. The Venus de Milo images will be discussed in a future essay–yet to be written.

For the recent Man Ray Max Dupain exhibition1 at Heide Museum of Modern Art, I contributed a catalogue essay on Dupain’s 1930s–early 1940s nude studies. I thought to include Shattered Intimacy as a nude but kept my text to the fleshy models. It is however in my view a nude.

In 1936 when he created Shattered Intimacy, Dupain also made the first bold nude studies in Australian photography. It was through nudes from 1934–1940 that Max Dupain announced his rupture from the prevailing polite romanticism of Pictorialist art photography. Nudes were virtually absent in the Pictorialist canon.

Dupain’s sophisticated surrealist assemblages and montages take their place in the most adventurous and accomplished modern Australian art of the 1930s. He had learned staging and lighting skills during his apprenticeship in commercial photography in the Sydney studio of Cecil Bostock from 1930 to1933. He had also undertaken some night classes at East Sydney Technical College2 and Julian Ashton’s Art School3 but relied largely on imported magazines and publications for models of a fundamentally different art photography.

The Standing Discobolus

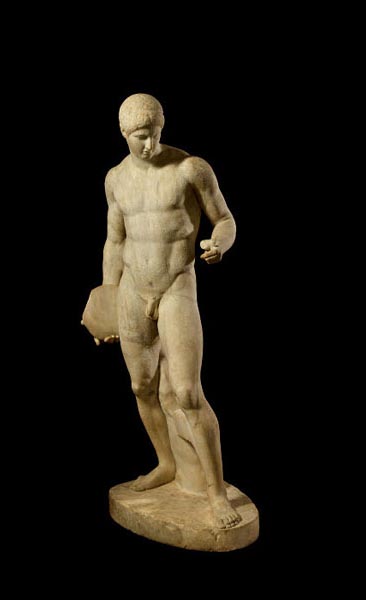

Shattered Intimacy features a broken miniature classical Greek figurine known as the Standing Discobolos, attributed to Naukydes (fl. c 420-390BC) but only known from a Roman copy held by the Vatican.

In its pensive mood this figure differs greatly from the famous fifth century sculpture The Discobolus by Myron, which shows an athlete in full swing just before release of the discus.

In Shattered Intimacy the Discobolus lies on his back surrounded by shards of the pedestal off which he has been violently knocked. His body is revealed by a shaft of light from above filtering down through a murky ‘watery’ space. The fragments of the pedestal are solarised and appear like bleached coral.

The beauty of the fine muscular body of the figure contrasts with the jaggedness of his now amputated limbs. He is being menaced by octopus-like tentacles. The dark shadowy shape around him looks like a bottle - the type that washes up on the shore line with messages inside. It is a picture of dislocation, vulnerability, isolation and loss.

The ‘seabed’ location for the composition in Shattered Intimacy suggests the figure references the Greek myth of Icarus whose fate was to fall back to the sea and death by drowning after soaring too close to the sun with his wings only attached by wax. But that would be far too conventional rather than a disruptive surrealist reading.

|

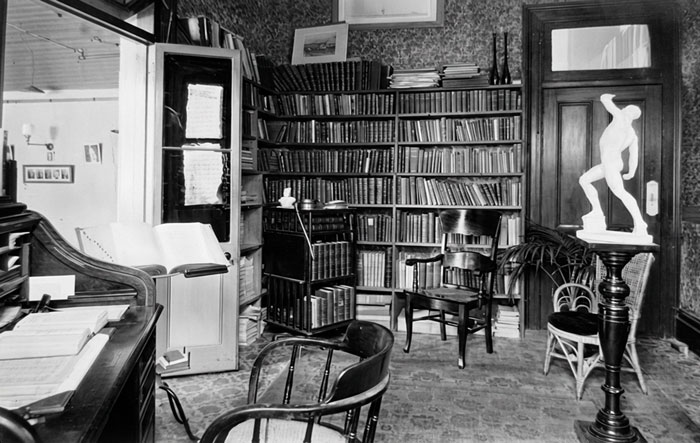

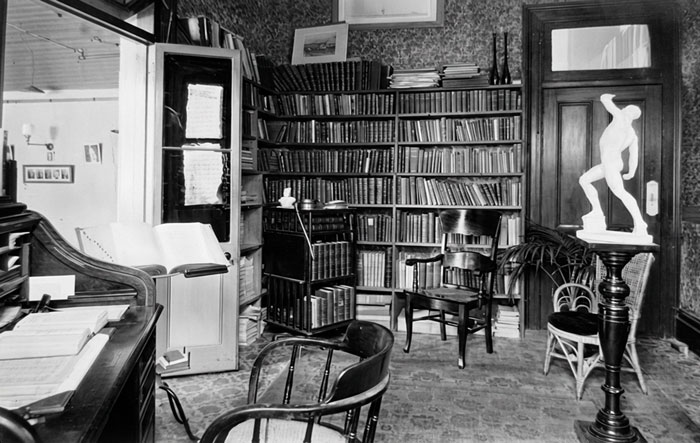

Interior of Dupain Institute gymnasium

illustrated in G.Z. Dupain's Are you Satisfied with Your Physical Condition? 1909.

Collection: Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW |

Whatever the original statuette represented of the nobility of ancient Greek athleticism or myth, here it has been broken.

A Freudian psychologist might read this vulnerability as male anxiety.

The Discobolos figurine belonged to Max’s father George Zepherin Dupain (1882-1958)4 a self-educated pioneer of modern physical culture and dietetics and zealous campaigner against contemporary physical and psychological decline. A drawing of the active Myron Discobolos appeared on the masthead of George Dupain’s short lived Dupain Institute Quarterly magazine in 1912. George Dupain was also a eugenicist but there is scant evidence Max Dupain shared such extreme views.6

George Dupain used a photograph of the Standing Discobolus as a frontispiece in his 1934 book Diet and Physical Fitness representing the ideal athletic body5. Later in 1948 he used his son’s nude study The Discus Thrower as the cover for his 1948 book Exercise and Physical Fitness.

The Dupain gymnasium was a large operation with boxing, fencing as well as body building and exercise classes for male and female members as well as school students. There were women instructors and notable female graduates trained there. The Institute presented regular elaborate public demonstrations and choreographed entertainments by male and female staff and pupils. Dupain Sr was proud of his own physique and performed muscle demonstrations at the Institute’s events.

By his late teens Max Dupain was in the Sydney Grammar School rowing team. He worked out at his father’s city gymnasium and took photographs of his father striking classical sculpture poses. Max retained a fine physique all his life and continued solo sculling in middle harbour until his last years. Contact and team sports did not appeal.

Max Dupain finished at Sydney Grammar in early 1930 but did not matriculate. He loved Shakespeare and romantic literature and some contemporary poetry at school. He could recite large passages of poetry all his life but did not aspire to be a writer.

It is too easy to skip over the influence of that ability but it required almost obsessive repetition to come off the tongue so easily until his last years. Those rather emotional and dramatic poems were constant companions as was romantic classical music of Beethoven. Dupain was a romantic at heart in his Pictorialist, modernist and later architectural, landscape and personal art photography.

Shattered Intimacy is in a very different emotional register to George Dupain‘s dense and pedantic writings. Although Max reported that his father was supportive of his career choice, there are no first-hand reports on George's attitude to his son's type of work or artistic ambitions. George’s own father had been involved with music but art seems not to have a Dupain family interest. Dupain’s mother Ena was interested in D.H. Lawrence which was probably quite advanced for a respectable married lady in the 1930s. Max Dupain made very few references to her influence in his interviews but their shared interest in poetry seems significant.

Max Dupain sought and was encouraged by advisors to a career exploiting his already quite skilled work as a photographer. He was already exhibiting romantic soft focus landscapes in the New South Wales Photographic Society in his last year at Grammar School. An introduction in 1930 secured him an apprenticeship with Cecil Bostock7 a Sydney commercial and leading Pictorialist art photographer.

Dupain found his apprenticeship hard under the austere Bostock who had little time for passages of poetry. But his teacher was well advanced in art photography and had adopted modern art deco geometric styling in his 1930s commercial and personal art works. Bostock also provided Dupain with a model of how to split a practice between creative bread and butter jobs and life as an active exhibitor of personal art photographs.

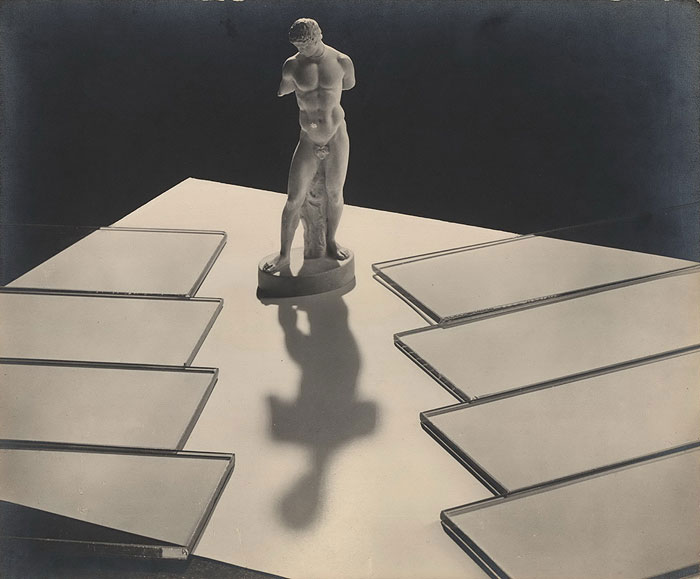

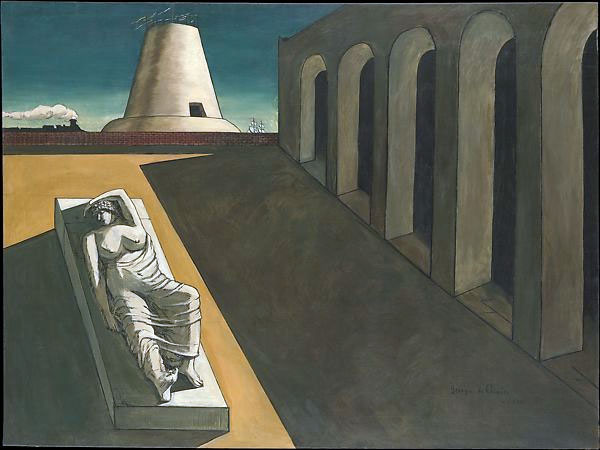

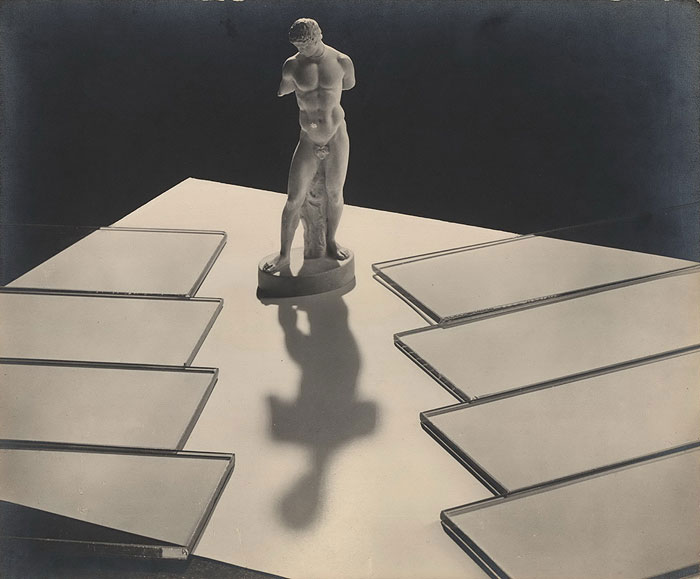

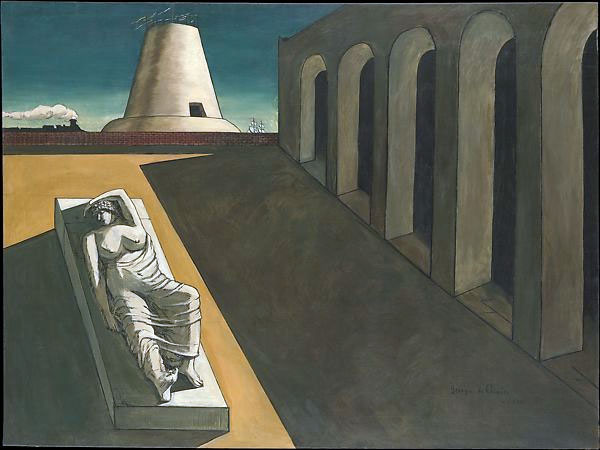

By his last year with Bostock, Dupain had begun a transition to a modernist geometric style. Opening his own studio in Bond Street in 1934 gave him freedom to experiment. The Standing Discobolos figure was first used in a modern geometric study, which Dupain published in The Daily Telegraph Pictorial section 15 May 19348. It has a touch of the mystery of early 20th century modern painter Giorgio De Chirico and Man Ray's surrealist assemblages which he knew through publications. The Telegraph would run quite a few of Dupain’s modern images.

The figure appears in a number of Dupain’s surrealist works in the 1930s.9 Surrealists frequently used classical Greek figures in conjunction with unexpected objects but not in nostalgia for the past but to disrupt the old order or as has been argued as symbols of ‘fraught sexual and psychological forces hidden beneath the surface of reality’10

|

| Max Dupain, untitled 1934 |

|

| Giorgio de Chirico - Ariadne Metropolitan Museum of Art NY |

|

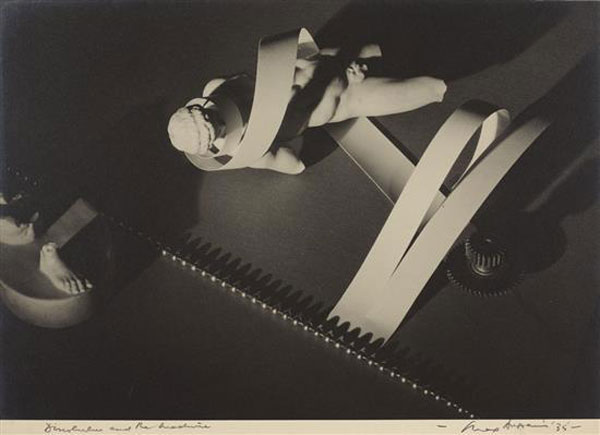

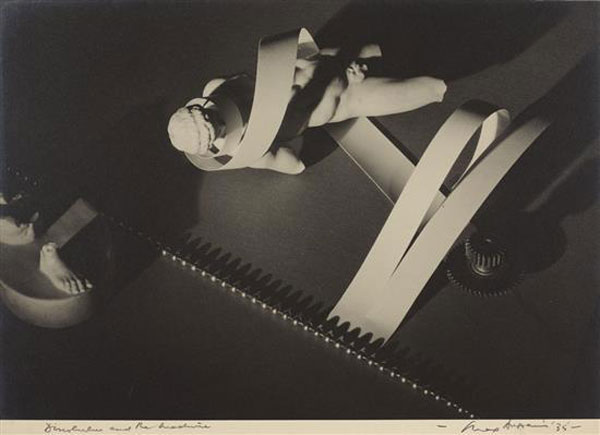

| Man Ray, untitled, 1931 |

|

| Max Dupain, Discobolos and the Machine 1935 |

Shattered Intimacy is dated 1936 and was made at one of the headiest and most creative times in Dupain’s career. It is titled occasionally by Dupain as Shattered Intimacy 1; but which work is number 2 is unknown. The same figure and paper tendrils appear in the work titled Discobolos and the machine dated 1935 in which the tendrils now trap the figure that has been knocked off its base. The view is vertiginous with cog and machine chain cutting through any order and serenity.

Dupain chose this image for the one man show that the Photographic Society of New South Wales gave him in March 1937 the caption in The Daily Telegraph of 10th March noting that ‘It depicts the destruction of classical life by the remote control of the machine'. Both works came just a year after Dupain wrote a review for The Home magazine in 1934 on American critic James Thrall Scoby’s monograph on the photography of Man Ray.

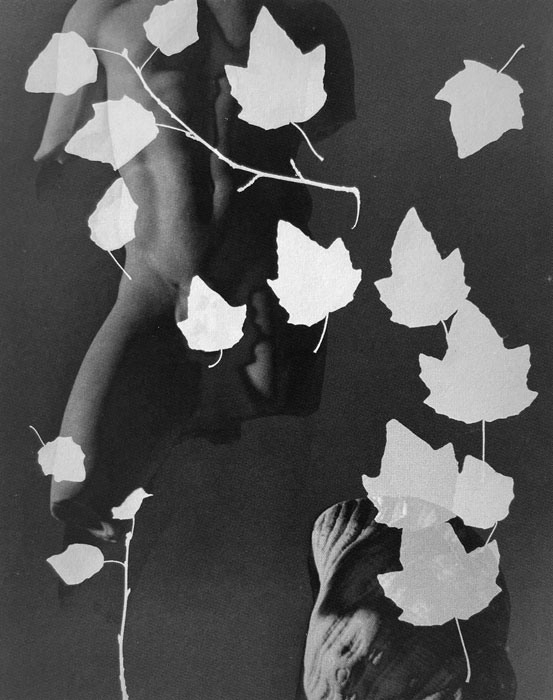

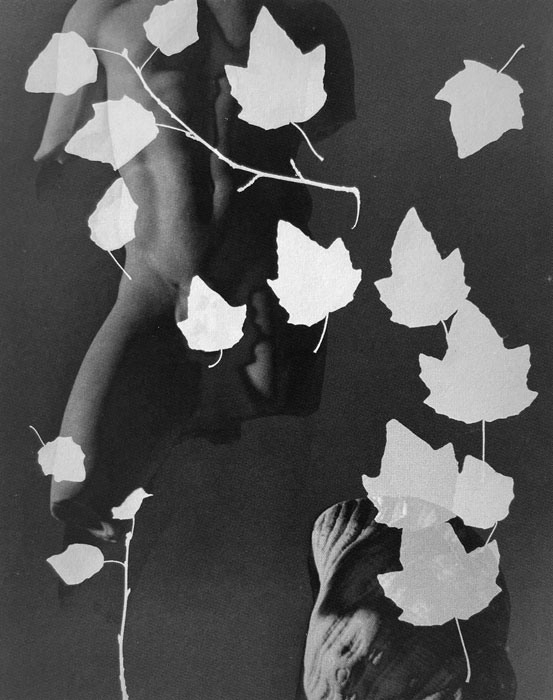

The exposure to Man Ray’s images ideas and approach inspired Dupain’s first published images of an overtly surrealist character with strange conjunctions of objects and amorphous eerie space. In1936 he made another montage of the Discobolus with a shell and solarised leaves

|

| Max Dupain, Untitled photogram 1936 |

To return to the image under discussion. What then is the intimacy that been shattered? What does such a poignant image of male vulnerability mean in 1936 to a young man on a rapid career rise at the start of his own studio.

A search for ‘shattered intimacy’ as a term brings up a host of usage of the past fifty years or so there is a suggestion that philosopher Hannah Arendt might have been the originator of a concept of intimacy in modern life that had been shattered. Her intention was not limited to sexual relations as a whole sensory and intellectual connection with the world. However, the title directly references of a 1931 book by British essayist and atheist Llewelyn Powys; a poet much admired by Dupain.

Llewelyn Powys argued people were just impassioned clay not god made. He advocated enjoying life, being happy. Modern society and men in particular were emasculated by servitude to machines and offices. Dupain identified with Powys but few who knew Max would have said that he was hedonistic.

An intriguing possibility in the pose of Shattered Intimacy is the echo of the Rayner Hoff sculpture Sacrifice in the Anzac War Memorial in Sydney Hyde Park whhich opened in 1934. Dupain was working for Cecil Bostock who had the commission to photograph the Memorial for The Book of the Anzac Memoria and would have carried that work out in 1933. The Hoff sculpture was designed to be seen from above and show the recumbent form of an ‘Anzac soldier whose soul has passed to the Great Beyond, and whose body, borne aloft upon a shield by his best loved – mother, sister, wife and child – is laid there as a symbol of that spirit which inspired him in life.’

Dupain had had a sheltered life. His father did not serve in WWI. Bostock did. The experience of photographing the War Memorial must have had painful associations for him. The experience of working alongside Bostock on the Memorial may also have affected Dupain.

Did young men coming of age in the 1930s know in their hearts that the world was ruptured by a war with monstrous machines? Physical development through fitness may have offered a refuge in the form of means to assert control at least over one’s body.

|

| Cecil Bostock photograph of the Rayner Hoff sculpture Sacrifice in the Anzac War Memorial in Sydney Hyde Park |

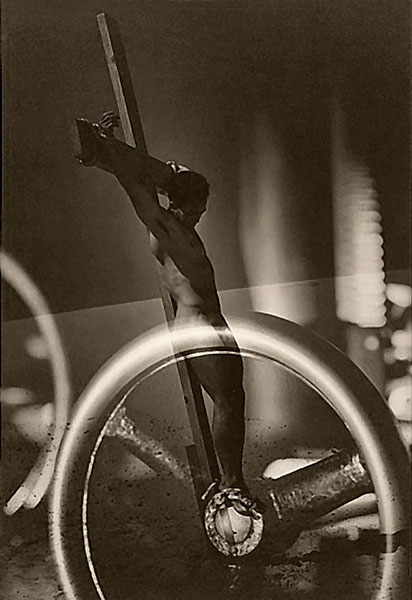

Max Dupain made use of the Discobolus in several other surrealist images of a more theatrical nature. In the same year as Shattered Intimacy he made The Apotheosis of Man a montage of the head of the Discobolus overlaid by a saxophonist wearing a gas mask. In Doom of Youth 1937 while not using a Greek figure has a man on a cross ground down by cog and with a serrated knife looming suggesting the sacrifice of youth.11

|

| Max Dupain, Doom of Youth 1937 |

Curiously while quite a lot of Dupain’s surrealist works were published or shown in the 1930s, there is no record of early exhibition or publication of Shattered Intimacy. Its influence and public life then would be minimal until included in the monograph accompanying the 1982 Max Dupain Retrospective at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. A number of surviving vintage exhibition quality prints of Shattered Intimacy survive and are held by the National Gallery of Australia and the Art Gallery of New South Wales as older style chloro-bromide warm toned prints.

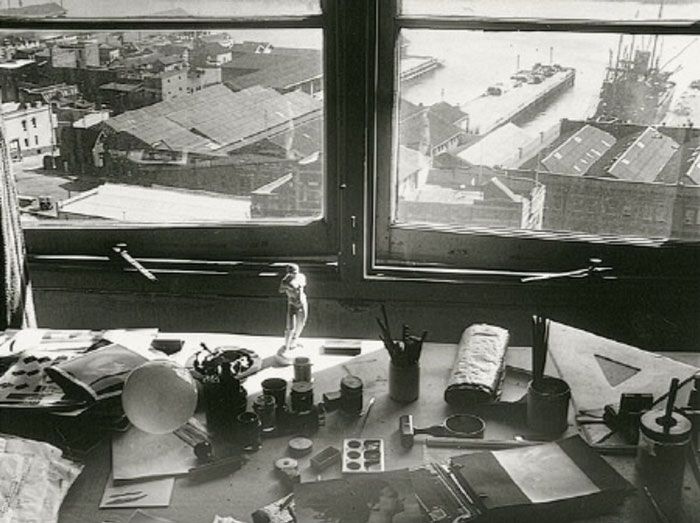

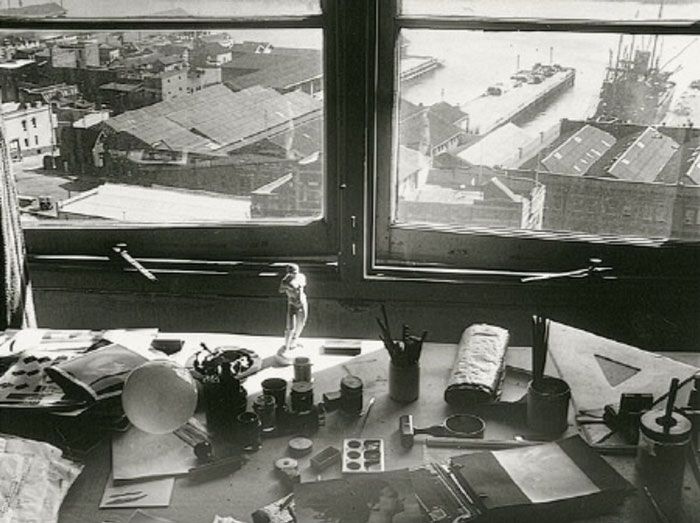

The broken Discobolos did get patched up as it appears repaired in a 1939 photograph on the spotting desk by the window in Dupain’s new studio in Clarence street. It was clearly a special piece he kept with him but I don’t recall it at his Artarmon studio in the 1980s and its current fate is unknown. Other uses in Dupain’s photographs have not been located.

Once the visual art work is created it is an expression but also independent of it own sources It is a different language that communicates visually. We make of the images what we will socially and personally in our own time. Shattered Intimacy remains for me a poignant image of human vulnerability.

|

| View from Max Dupain’s studio Clarence Street Sydney |

Notes:

- The Heide Museum of Modern Art ( Melbourne) 2025 exhibition Man Ray and Max Dupain

- The East Sydney Technical College was originally an annexe to Sydney Technical College, it operated independently between 1955 and 1996 when it became the National Art School.

- Julian Ashton Art School (Sydney) 1890–present

- George Zephirin Dupain (1881-1958)

- George Z Dupain, Diet and physical fitness : a popular treatise on nutrition as a means to greater efficiency, a finer physique, better health, and a longer life Sydney : Briton 1934. Alfred Briton was a body builder from England with various mail order businesses and a magazine Life and Heath for which Dupain wrote regular columns. Max Dupain’s nude figure study The discus thrower was used as the cover for GZ Dupain’s 1948 book Exercise and Physical Fitness.

- For a detailed study of George and Max Dupain’s involvement with theory and practise of physical culture see Isobel Crombie Body Culture: Max Dupain, Photography and Australian Culture, 1919-1939 , Peleus Press, 2004.

- Cecil Bostock 1884 (England)– 1939 (Sydney)

- The Daily Telegraph ran a number of Dupan images of the more strking modern style from the opening of his studio in May? 1934 The paper pictorial favoured dramatic photographs.

- For Dupain’s involvement with surrealism and body culture see Helen Ennis Max Dupain a Portrait, Harper Collins, 2024 and Isobel Crombie Body culture : Max Dupain, photography and Australian culture, 1919-1939, Peleus Press in association with the National Gallery of Victoria, 2004. Ken Wach's essay ' Subjectivity incorporated: the surrealist vignette in the photography of Max Dupain', Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art 1 (1) :107130 May 2015 for the most insightful analysis of the place of Dupain in Surrealism.

- Nicole Entin, The Greek Myths are profoundly rooted in us’

The influence of antiquity on Surrealism. August 6 2025

- Isobel Crombie in her online thesis 'Body Culture: Max Dupain and teh social reecreation of teh body, c.1919-1939, Melbourne University 1999.' pp.180-81.

I am planning another essay on Max Dupain’s suite of images using the Venus de Milo figure.

I had been intending to write this essay for many years. (decades!) The final catalyst was being involved with

the 2025 Heidi Museum of Modern Art (Melbourne) exhibition Man Ray and Max Dupain

and the accompanying book (sold out) - Lesley Harding (ed) Man Ray | Max Dupain, Heide, Melbourne 2025

Gael Newton AM January 2026

more on Max Dupain

more of Gael Newton's Essays

|