Max Dupain

essay by Max Dupain January 1978

the 2017 online version of the 1978 essay originally published in Light VISION 5 *

The technique of etching and that of oil and watercolour painting and sculpture has not changed basically for hundreds of years. They are established mediums. What remains to be done with them is forever an eternity of exploration and adventure.

Not so with photography. Every month in the picture magazine there are pages devoted to new gadgets, new flash units, new automatic devices with which to do something differently and more quickly than before; in short, to gratify the whims of mechanically minded amateur photographers and create a profitable industry out of profitless indulgences.

Those who practise this gadget ridden 'folk art of twentieth century people' have substituted 'nostalgia' for 'opium'. Because in the long run this element, this photo soporific, is the sum total of their efforts.

After nearly half a century of pretty close involvement in photography I'm convinced that we have to assess the product of this art of ours by its significance. So much of it is banal and trivial and meaningless. There is currently a rash of urban landscapes appearing in every magazine you pick up, and the majority of these pictures are boring and proletarian.

On the other hand there are photographers with a great sense of discipline, who work with unsophisticated equipment and who possess an acute sense of selection and spontaneous composition. They are able to extract every ounce of pictorial sensibility from their subject, and I support their doctrine to the last. Sensitivity, piercing awareness, emotional and intellectual involvement, self-discipline are some of the elements which create that rapport with the subject, be it a rock or a woman or a woman on a rock!

Once this is established, and it takes only fractions of seconds, the camera takes over. But without that subjective liason as the first flash upon the inward eye, the result is almost always sterile and useless.

Subject matter comes to you, you don't go to it (as in Russian television — it watches you!) Like a theme which comes to a composer; straight from heaven; three or four notes and you've got it to work on, to elaborate, improvise, exercise counterpoint until you have a symphony or concerto based on that original theme of several notes.

Likewise you may be on a walk through the bush, a street, a park or driving to work, and spontaneously an inner voice will call out to you and behold, there it is. Although I shoot extemporaneously a lot of the time, I prefer to have half a dozen shots in my mind. Probably I have seen them many times under different conditions and have been thinking about them.

The moment will come when I shall go to them and make the photographs (in black and white!). I find the contemplation of the subject brings it closer to you, and when you are there face to face and under the stress of knowing this is it and there's no turning back, something just goes bang inside and it's all over. I'm sorry I cannot give you a formula for this one; but I stress two things, simplicity and directness. This means reduction of the subject to elementary or even symbolic terms, by devious selection of viewpoint, by lighting, by after-treatment. I do not always print the total negative.

This practice has become a bit of a fetish. What the hell? The result is all that matters. Also I work mostly in black and white — it suits my will to interpret and dramatise. I have more control with black and white, without which the personal element is lost forever.

Working as a professional photographer in insular Australia has been my self chosen lot. In such a 'cultural backwater', as Norman Lindsay expressed it, mental stimulation is anything but overplus, especially the further one moves into the rural regions. So one is thrown up against one's inner resources, and visual excitement comes from over there by proxy in picture books and printed text; music, poetry, painting and sculpture provide the vital ingredients for soul fodder in the local scene.

Direct influential impact is at half strength capacity. I think this is a good thing if one has the courage and endurance to sustain and promote his individuality by sheer brute assertion of belief in himself. God help those who can't muster this will unless they migrate, absorb and return to us, temporarily stimulated and refreshed, but possibly as other human beings lost to their real selves in the wilderness of the world's pictorial paradise.

After reading over what I have written, I am reminded of an article by Beatrice Faust in No. 2 issue of Light Vision. She declares, "There is an incredible amount of bullshit being written and spoken about photography", simultaneously adding her share to the heap! At the same time, she issues an alert against the seduction of words. No doubt her findings are correct, but they do not pertain only to photography; the whole subjective world is full of it.

The prime endeavour of art critics and writers about aesthetic matters is to enlarge the chimera which is emitted by their subject and recreate the dictum that 'all is illusion'. Let's not talk too much, there is a great deal of material out there to be taken hold of, grappled with and hammered down into beautiful photographic prints. Let's get on with it.

By the way, this credo establishes a very personal attitude to the art I practise. Great art is not personal; it's impersonal. Shakespeare is not personal, he embraces all men. Beethoven is not personal, he reaches heights beyond this earth. How about Rembrandt? that light is divine. Listen to the Gods entering Valhalla in Wagner's Rhinegold, and think of photography. I dare you!

Max Dupain, January 1978.

THE PLATES

Photograph at top of page: Kerosene Lamp, 1929

-------------------------------------------------------------

2. Nude 1938

3. Two Forms, 1939

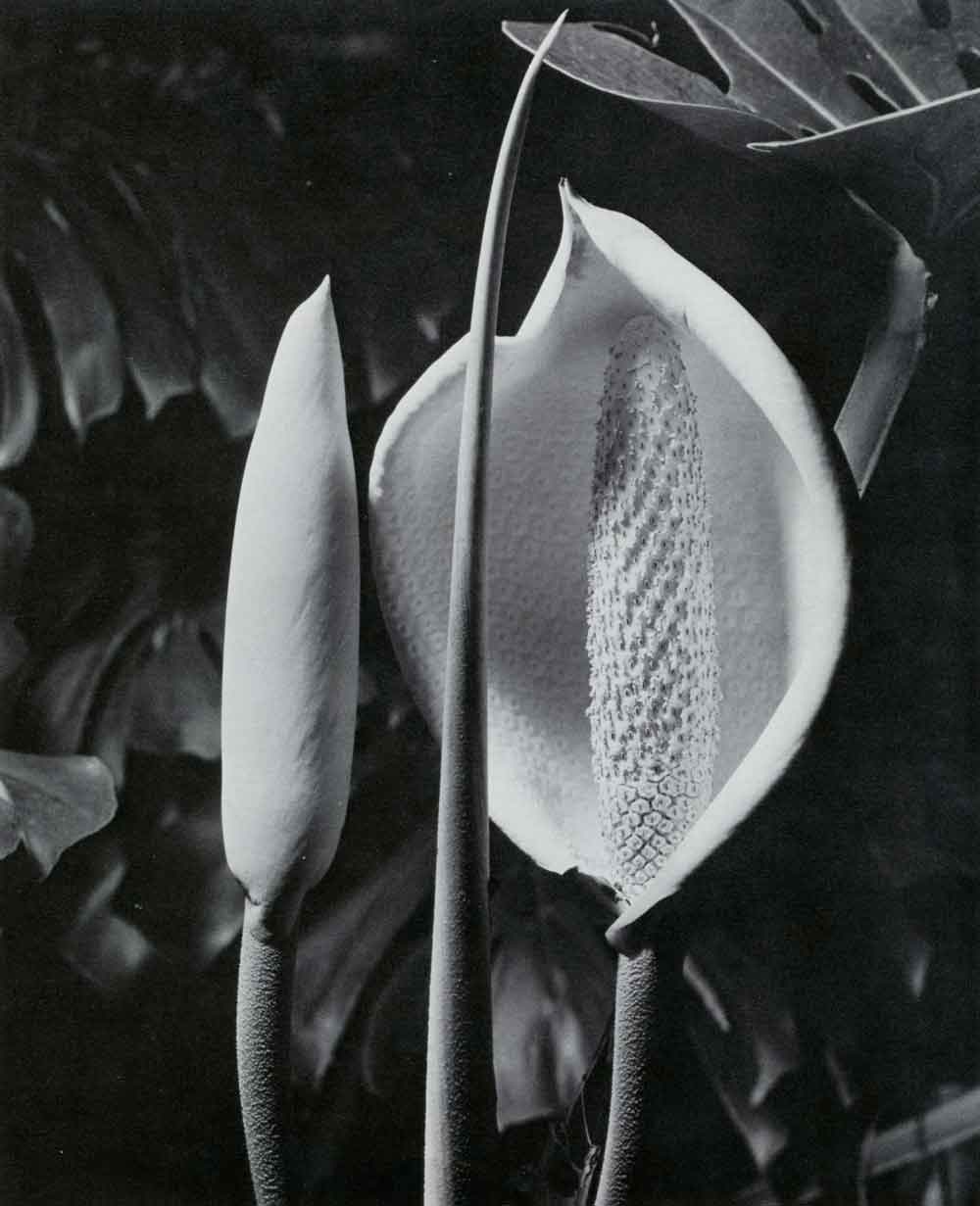

4. Monsterea Deliciosa, 1965

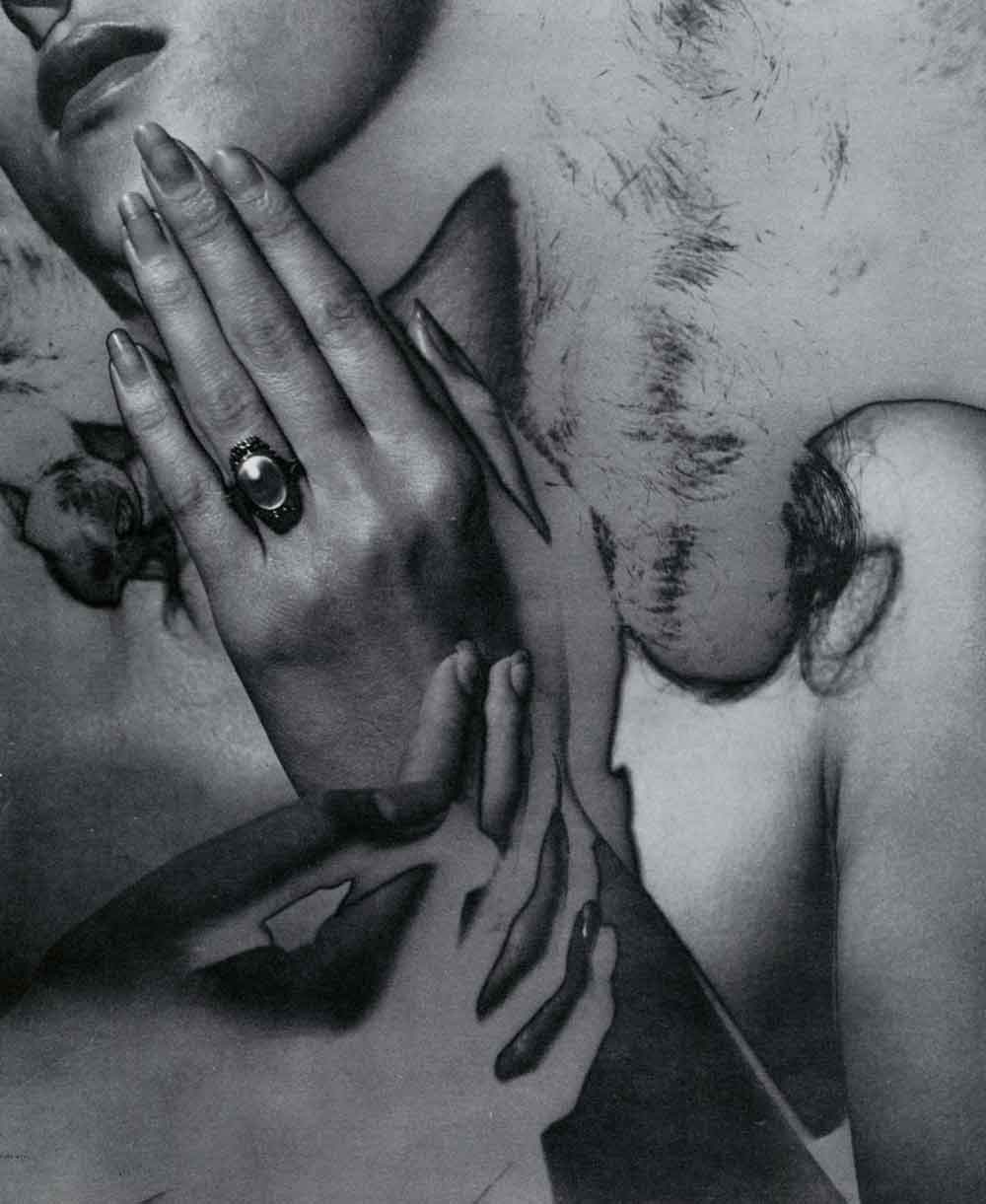

5. Homage to Man Ray, 1937

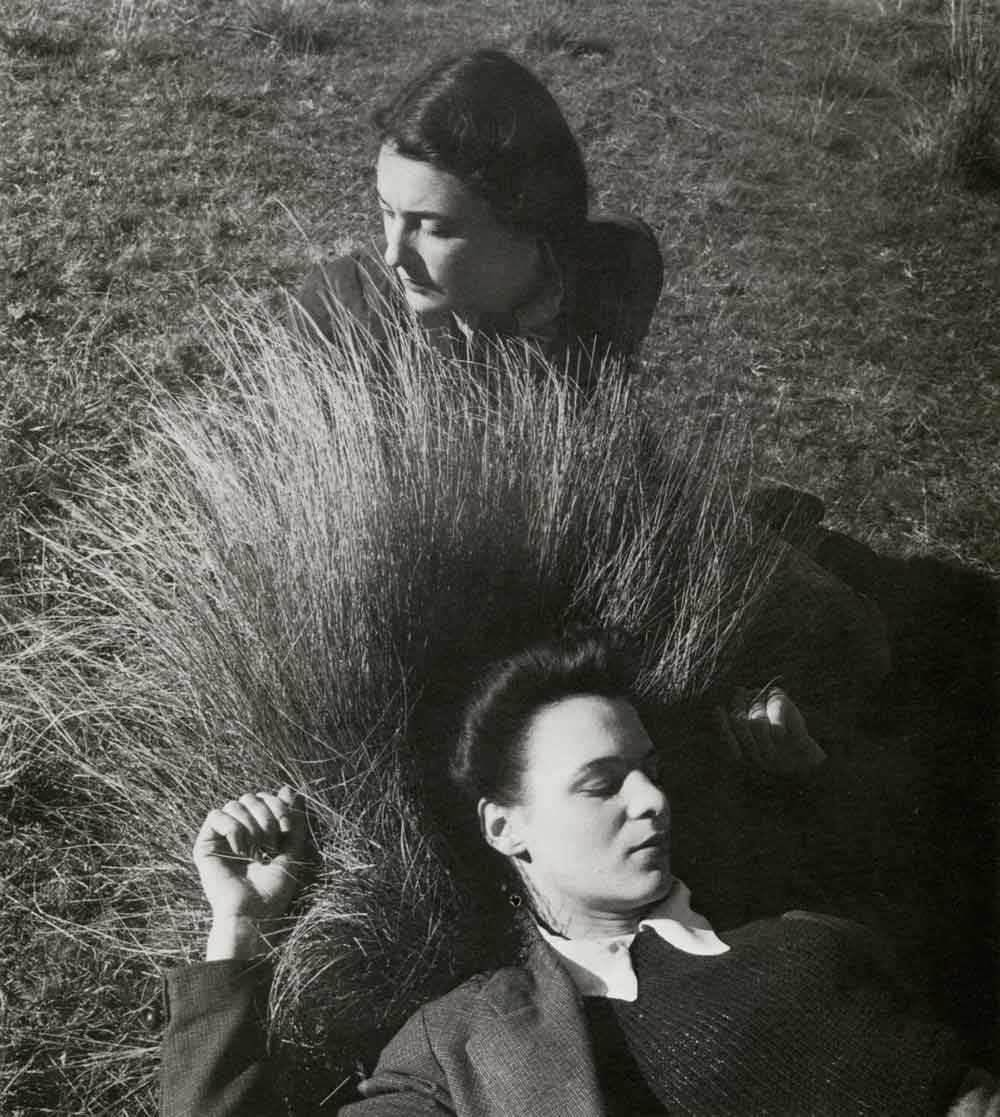

6. Two Girls, 1939

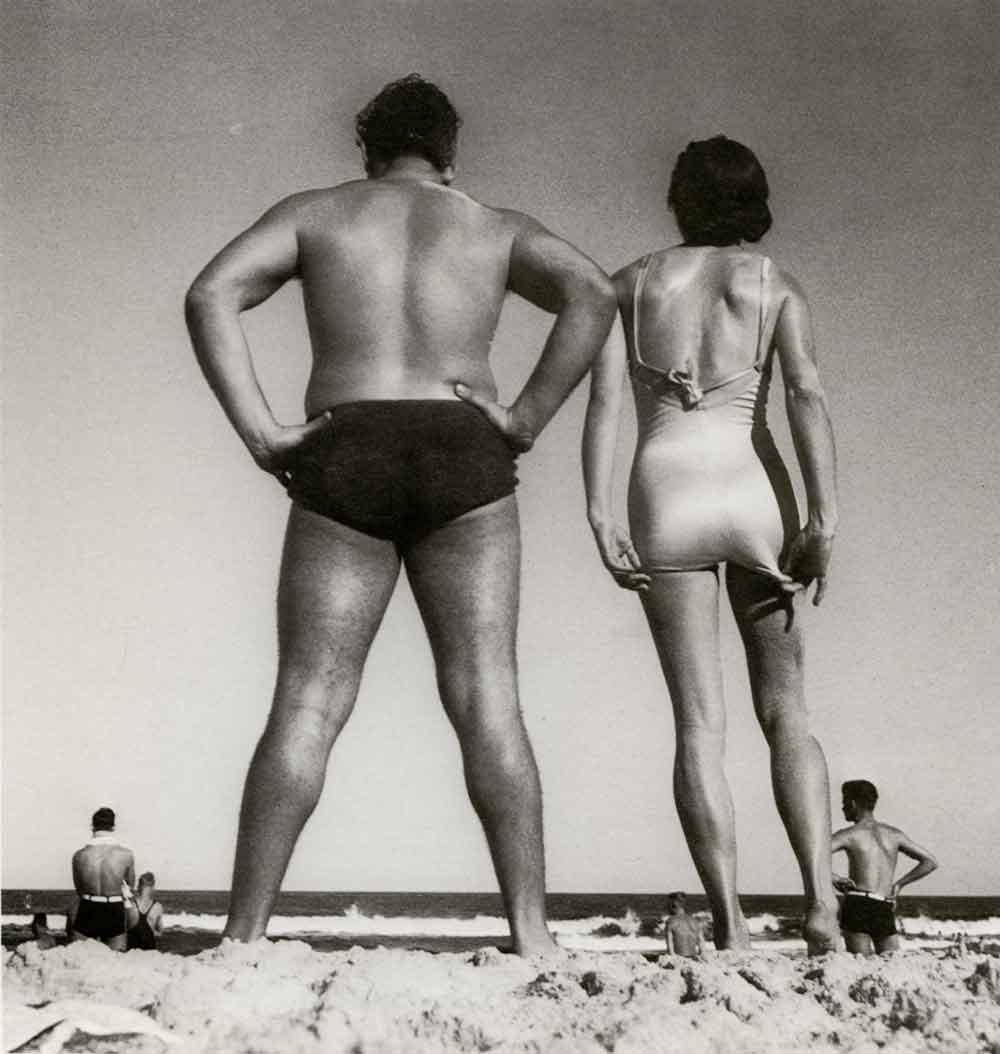

7. Bondi, 1939

8. Meat Queue, 1946

9. Street at Central, 1938

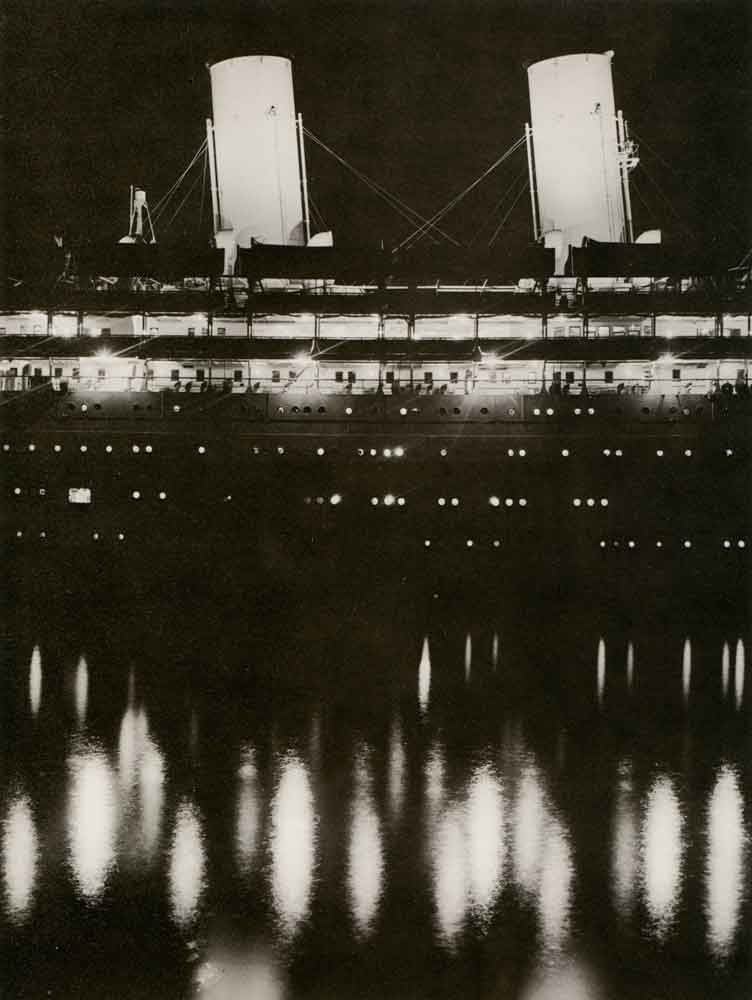

10. Liner at Night, 1940

11. Silos at Pyrmont, 1937

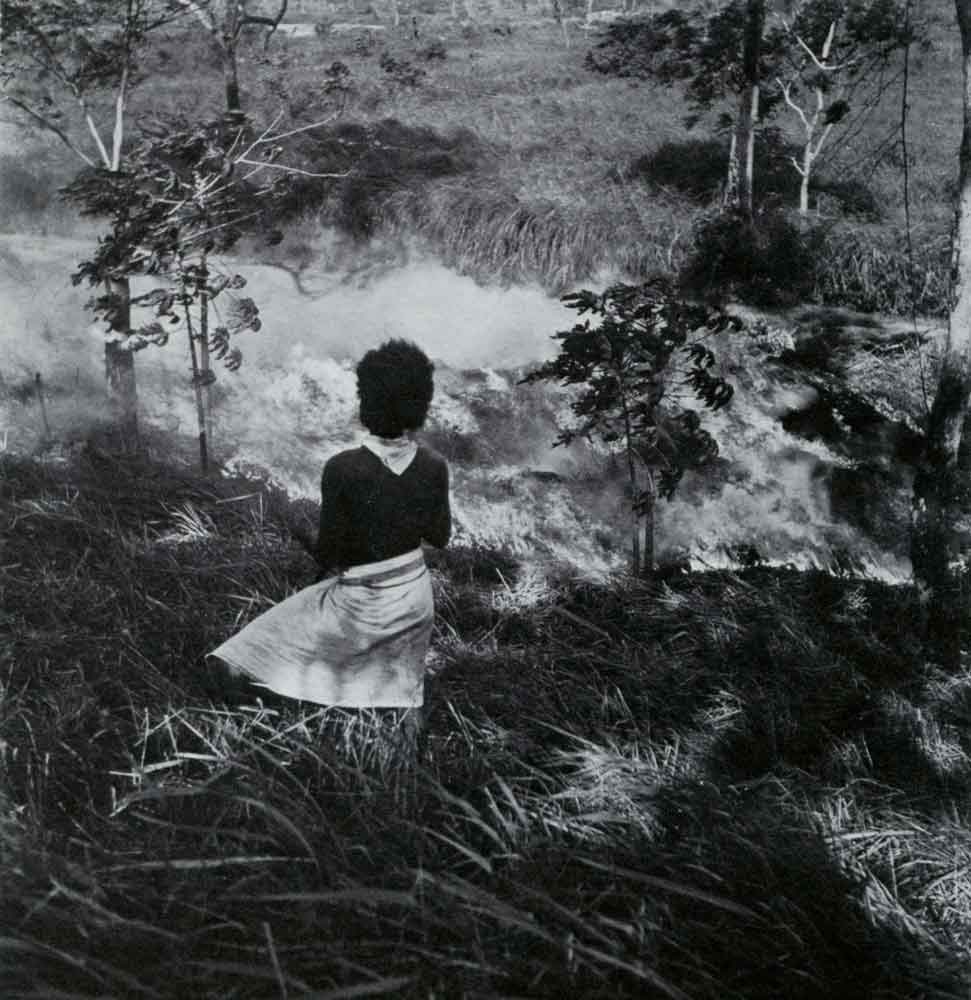

12. New Guinea Landscape, 1943

13. New Guinea Landscape, 1944

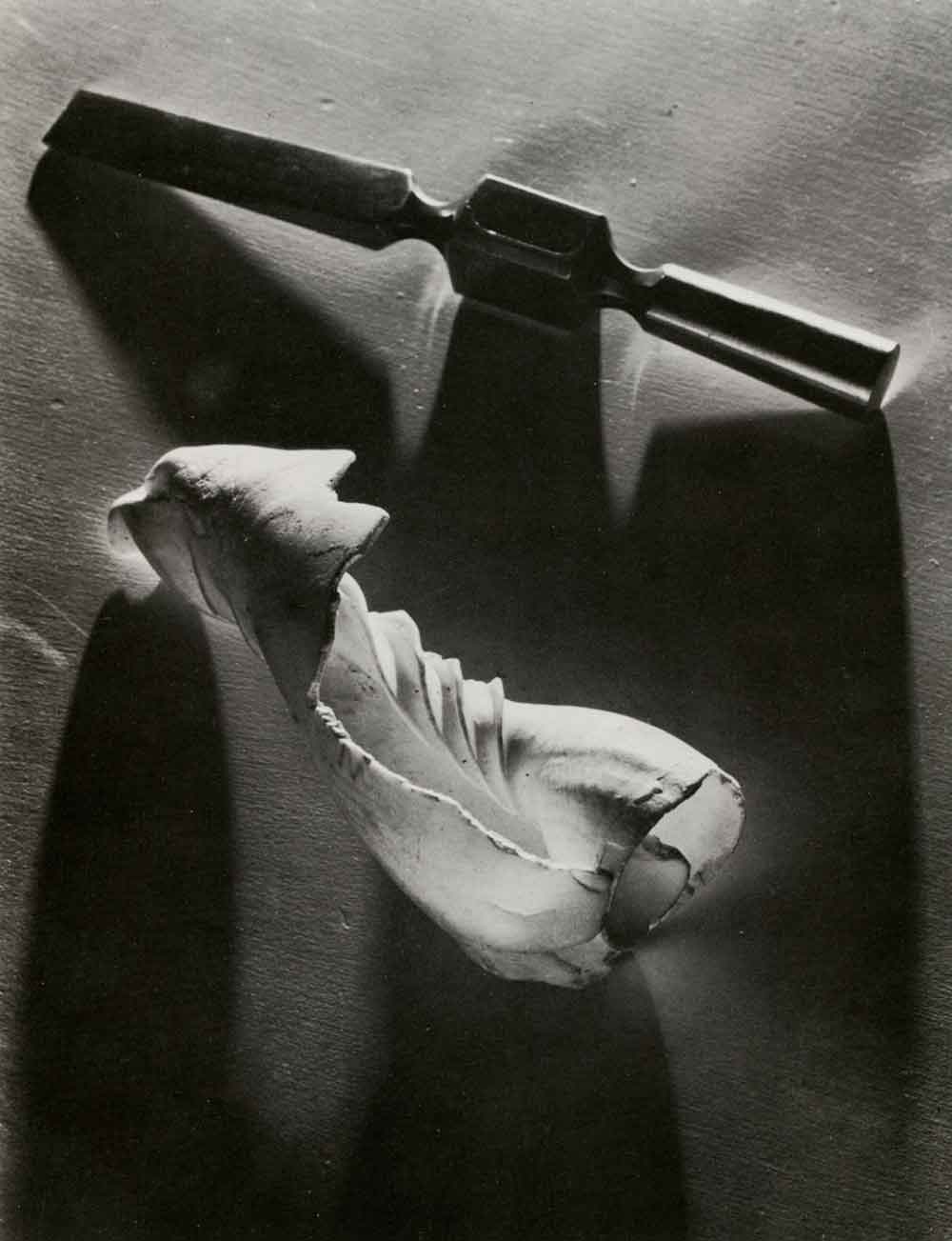

14. Found Thing, Canberra, 1976

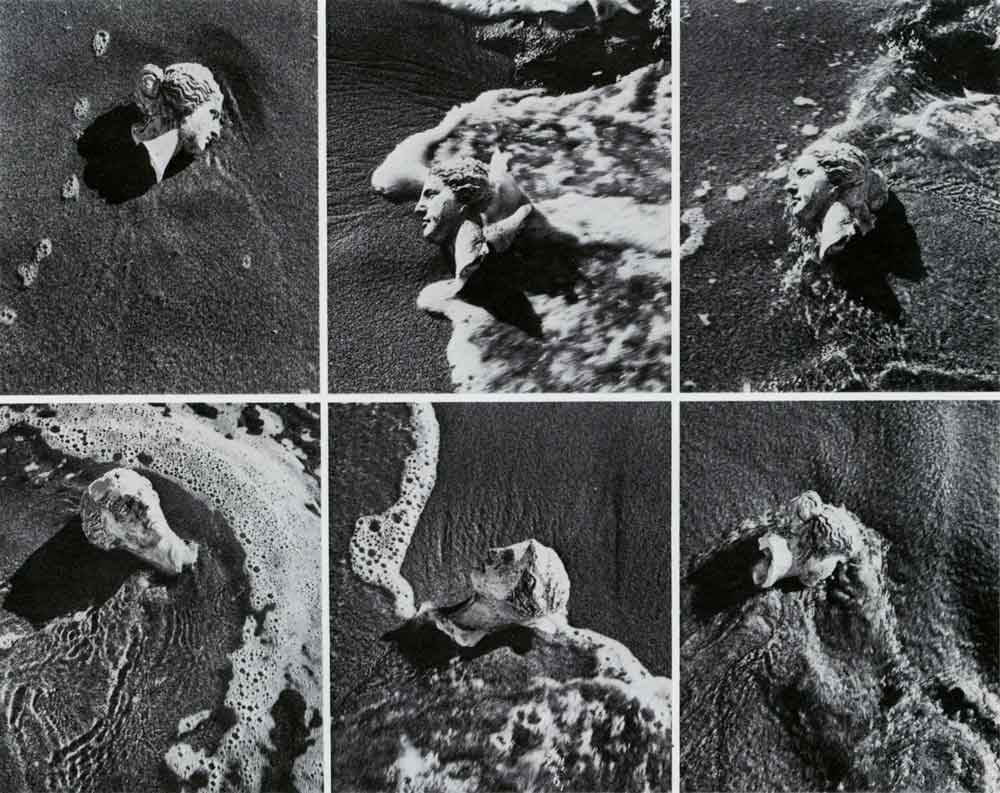

15. Souvenir of Newport Beach, 1975

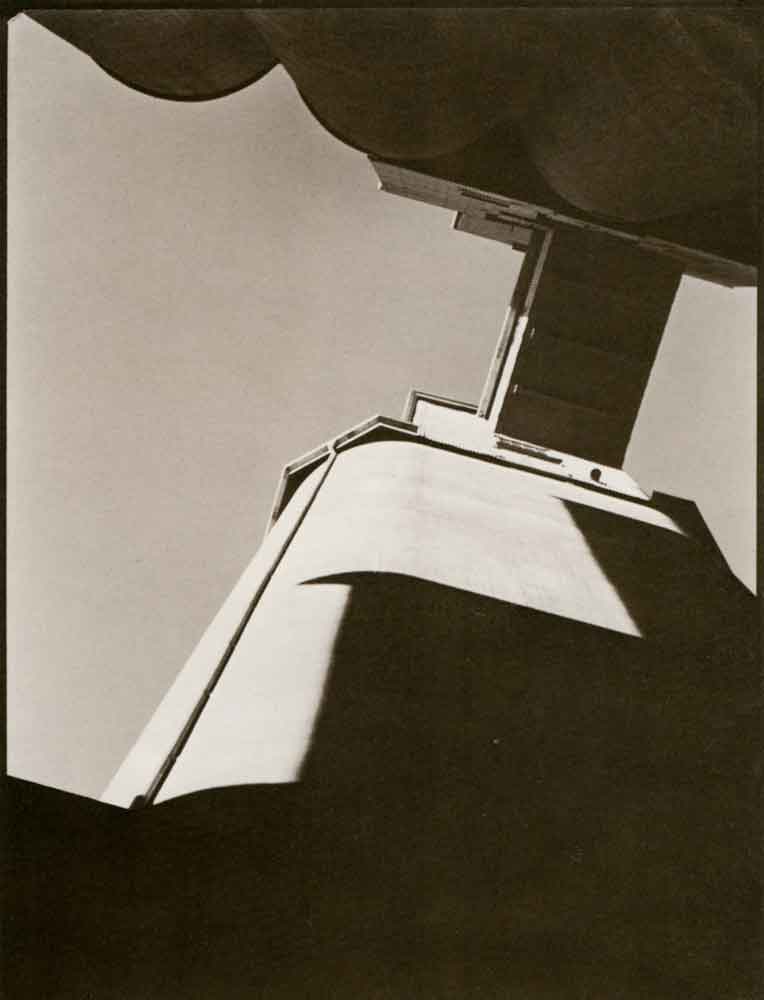

16. Stair Rail, 1975

Click here for the accompanying essay by Gael Newton - also published in Light VISION #5

Click here for other research papers/ essays / articles by Gael Newton

|