|

Art Photographer contents page

JOHN KAUFFMANN 1864–1942

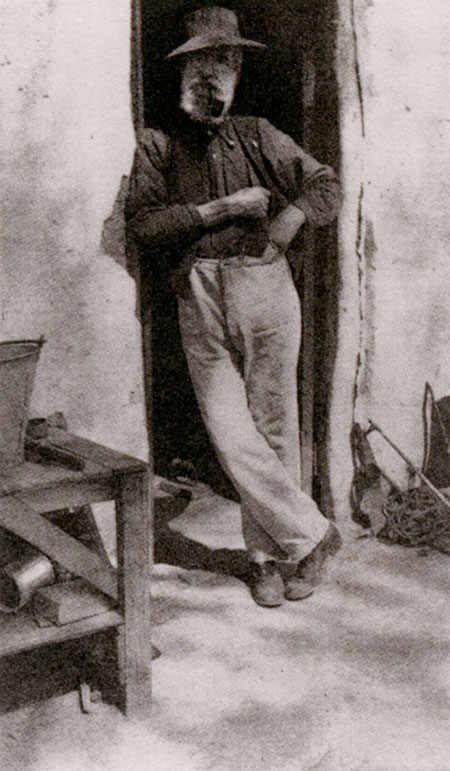

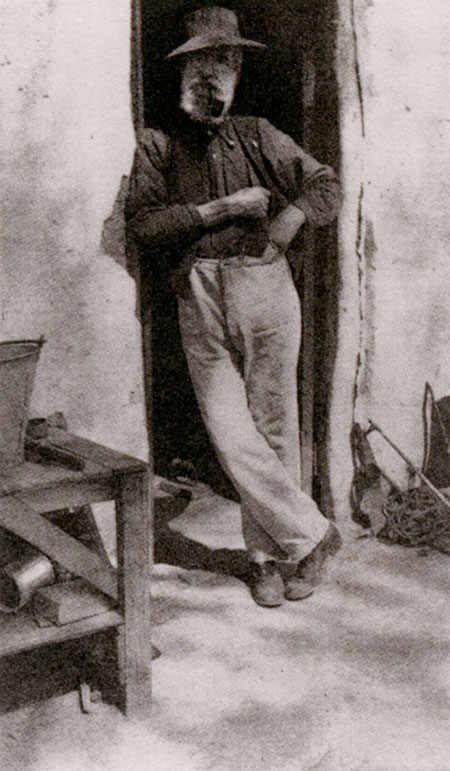

He was never quite one of us, those years in Europe having left him a confirmed Continental.

He was 6ft. 3ins. tall, very dignified and quiet, and seriously preoccupied with his thoughts. I knew him for thirty years, saw him almost every week, yet never knew him to smile.

He was one of the best-dressed men in Melbourne; one would always note his 'Red Indian' profile as he strolled 'The Block' complete with yellow gloves, cane, spats and his pince-nez on a silk cord.

He was usually off to an art exhibition, a chamber music recital, or an alfresco lunch in the Botanical Gardens, where he could find again something of the spirit of the Vienna Woods.

(Jack Cato, The Story of the Camera in Australia, 1955.1) |

|

|

John Kauffmann, Melbourne c.1915

Van Dyke studio - private collection |

Clearly, from this pen portrait, John Kauffmann was not 'one of the blokes' (something of a sin in the ethos of Australian mateship). His dandy attire, which included a long cape, was remembered by all who met him. One of his former pupils recalled Kauffmann's fondness for conjuring tricks, and believed he modelled himself on Sherlock Holmes. The legendary sleuth's creator, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, was one of Kauffmann's favourite authors.

Although Kauffmann distinguished himself in photographic salons from 1897-1942, he did not play any leading role in photographic societies, nor did he fraternise with other photographers. Thus, to those outside his personal circle, he appeared aloof and vain. By contrast, with his family and friends Kauffmann was affectionate, entertaining and enthusiastic about photography as an art. He liked to draw, paint in watercolour and play the violin. Kauffmann never married, but there may have been liaisons.2

Although Kauffmann began exhibiting in 1897 and apparently held no other photographic employment from that time, he did not open a studio until 1917. His several studios were all in Collins Street, the central business block in Melbourne. Kauffmann rarely advertised, and did not tout for business as his colleagues had to do in the highly competitive field of commercial photography.3 He sold his prints at quite good prices and undertook some commercial assignments in the 1920s and 1930s, but did not have an obvious bread-and-butter line of work. Jack Cato has assumed that Kauffmann had a private income, although this is not confirmed.4

Cato's emphasis on Kauffmann's fine style and aloof manner suggests that his appearance and lifestyle were the perfect accompaniment to the removed and idealising beauty of Pictorialism. Cato further expresses an established judgment against the un-Australian sombreness of pioneer Pictorialism, in concluding that Kauffmann's works had 'great refinement and dignity and a sense of poetic beauty, but it is the solemn, silent beauty of twilight; there is no sun or spontaneity in them, they are as unsmiling as was John himself'.5

After World War I the work of Pictorialists like Kauffmann was increasingly dismissed as well-meaning but misguided, and untrue to the Australian experience, light and landscape. Kauffmann died in 1942, aggrieved that his role in pioneering an expressive photography had not been better acknowledged. It was not until later that his younger and more successful contemporary, Harold Cazneaux, paid tribute to him in an article written in 1947,6 and the acknowledgments included in Cato's account were published.

In general, John Kauffmann chose not to speak for himself or his art. There are no articles, no letters, no memoirs, no statements about Pictorialism. He believed that the beauty of his pictures spoke for itself. In 1919 a finely produced portfolio of twenty of Kauffmann's landscape and urban studies was published by Alexander McCubbin in a limited edition of 500 copies. Simply titled The Art of John Kauffmann, the publication has the distinction of being the first monograph on an Australian photographer.

The biographical notes and picture commentaries by Leslie Beer provide the major source of information on Kauffmann's career and, to a lesser degree, his understanding of art photography. One of the few indications of Kauffmann's aesthetic is a quote in the monograph from the writings of P.H. Emerson: 'In landscape the artist should give the suggestion of a fairer creation than we know. The details and prose of nature, he should omit, and give us only the spirit and splendour.'7

John Kauffmann was born in Truro, South Australia in 1864. He was the second son of a storekeeper, Alexander Kauffmann, a German-born Jew, and his wife, Therese, from Clare, South Australia. The family moved to Adelaide in 1868 and operated merchant, mining, milling and importing businesses. Nothing is known of Kauffmann's early education.

Between 1881 and 1883 Kauffmann was an articled clerk in the office of the Adelaide architect John Harry Grainger, father of the composer-pianist, Percy. Kauffmann's employment with a cultured architect, and his later enrolment in the 1886 autumn and winter terms of evening art classes run by H.P. Gill, director of the School of Design, Painting and Technical Art in Adelaide, indicates his early orientation to the arts. He did not follow his elder and only brother, Louis, into the merchant's trade. Louis was formally brought into the family business in 1883, after a period of commercial studies in Switzerland.

In 1887 John also travelled abroad to London, where he joined the office of the prominent English firm of architects, Mackmurdo and Home.8

In The Art of John Kauffmann Leslie Beer includes and emphasises A.H. Mackmurdo's accomplishments as an art critic, collector and connoisseur, as well as editor of the Hobby Horse arts magazine. It would have been a congenial working environment for a young man interested in the arts.

Nevertheless, and after only one year, Kauffmann abandoned architecture to devote himself to two years of study with an unnamed analytical chemist. By this time he possessed a camera and was taking photographs on weekend and holiday sketching trips around rural England.

Kauffmann's understanding that photography could be an art (rather than an aid to drawing, or a hobby) was the consequence of his seeing an exhibition at the Photographic Society in London and the work of the pioneer Pictorialists Alfred Horsley-Hinton and H.P. Robinson. |

|

|

Leslie Beer, in describing Kauffmann's discovery, wrote:

He was now realising that, through the medium of photography, he could attain what was always his great desire, namely to express, pictorially, the beauty and poetry that nature had already revealed to him. Like many exponents of the camera art, Kauffmann lacked manipulative skill with the brush and palette, although possessed of a fine perception and sensitive appreciation of beauty. Photography was the true metier for him, and the camera was in future to be his vehicle of artistic expression.9

In the 1890s Pictorial photography opened the way to a career as an artist or an identity as an aesthete for many who lacked facility in the fine arts or academic training in painting and drawing. The availability of cheap mass-produced cameras and printing papers in the previous decade had given rise to legions of experienced amateur photographers. New photomechanical reproduction accelerated the spread of visual culture in general, and journals and magazines provided instruction for amateurs.

During this era, most of the individuals who embarked on voyages of self-discovery through the practice of art photography hailed from the middle class. Many remained amateurs, holding themselves aloof from commercial photographers, and were often the children of merchants or minor professionals. The most famous of this group was the American photographer, Alfred Stieglitz (like Kauffmann, also born in 1864, the son of a Jewish-German merchant family).

In the 1880s, Stieglitz abandoned engineering to study photography and photomechanical reproduction in Germany. Kauffmann's young countryman, Harold Cazneaux, would undergo his conversion in Adelaide in the late 1890s, after seeing work by Kauffmann and overseas Pictorialists in the local photographic salons.

Kauffmann's decision to pursue a professional career as an artist photographer was made in England and, shortly after, he moved to the Continent, spending three years studying chemistry at Zurich University (c.1893-96).

He spent six months in the Vienna studio of a fashionable portrait photographer (his only professional experience); a year studying reproductive phototechnology in Groenbach, Bavaria; and was a student of the renowned photochemist, Professor Josef Eder, at the Imperial and Royal Institute for Teaching and Experimentation in Photography and Reproduction Processes in Vienna. 10

Kauffmann also attended exhibitions of the Vienna Camera Club, then at the forefront of innovation in the presentation of Pictorial photography exhibitions.

He made several visits to Munich, visited Italy and holidayed in Paris before returning home to Adelaide in early 1897. By this time it is likely that Kauffmann had regular contact with a photographic society in Britain or Germany and had probably begun to exhibit.

Precise details and confirmation of Kauffmann's activities overseas have proved elusive. However, from the standard of work done on his return to Australia, John Kauffmann was clearly well-versed in the techniques and aesthetics of Pictorial photography by the time he left Europe.

His style was conservative, closer to that of the British school as practised by Horsley-Hinton, rather than the more daring Europeans such as Heinrich Kiihn, who favoured a more graphic approach.

Kauffmann's vision was influenced by Pictorial photography's revelation: the scene recorded by the lens could be transformed into the 'ideal' through masterly printmaking.

Kauffmann's earliest known images are village and lake scenes from northern Europe.

These prints in the carbon process, with their dark masses and intricate details, recall the rustic or picturesque scenes of the mezzotint; they are pleasant contributions to this graphic arts tradition. At some point Kauffmann discovered how to treat the elusive elements of light, reflection and atmosphere. |

|

|

Henrich Kuhn, Herbstabend am moor (Lakeside, Autumn Evening)

1896 Gum Bichromate photograph |

|

John Kauffmann, On the Lago Lugarno 1894

drawing from his European sketchbook |

|

| John Kauffmann Boat and Lake Lugarno 1894 |

His access to some of the most advanced research on plate and paper sensitivity, through his European teachers, no doubt helped his discovery. By 1894, Kauffmann's photography had far exceeded his drawing abilities, as can be seen by a comparison of his works in the two mediums.

One might expect that Kauffmann's qualifications would have led to employment in process work or studio photography, but for over a decade after his return any employment he had was as a clerk. The family business, Alexander Kauffmann & Son, had survived the depression of the 1880s, but by 1894 his brother Louis had married and left for Melbourne, where he started his own importing business.

Regardless of any hopes his parents may have held for his joining the family business, his European years had made John Kauffmann even less suited for the merchant trade.

By July 1897 Kauffmann had joined the South Australian Photographic Society (formed in 1885).11 His former art teacher, H.P. Gill, was an active member.

Kauffmann pursued recognition with confidence, energy and astuteness. He quickly organised for enlargements of his negatives to be made on the new bromide papers.12

In a bold move, he submitted these enlargements directly to the Society of Artists in Sydney for inclusion in their annual exhibition, rather than to a local photographic club exhibition. Kauffmann may have heard that the Society of Artists was under pressure to allow graphic and design artists into its exhibitions, rather than confining these events to painters and watercolourists. The Society promptly rejected photography, but posters and other graphic arts were included for the first time in its Annual Exhibition in November 1897.13

|

| John Kauffmann After Sunrise, Victor Harbour (South Australia), c.1900 |

Kauffmann ensured that the press were aware of his attempt to have his prints accepted by the Society of Artists.

In October, one month before the exhibition opened, the prints were exhibited at the Sydney showrooms of the prominent photographic supplier, Baker and Rouse, and at their Adelaide premises. The Sydney paper, The Australian Star, reported on the work as 'beautifully fine ... the delicate tones and tints being brought out in a clear and perfect manner'; a week later, the Australasian Photo-Review described how the prints were on the new Pearl bromide paper, and 'full of detail, yet beautifully soft... Mr Kauffmann is an artist as well as a photographer'.14

The press responses show that Kauffmann's work was clearly distinguished not for any departures from the conventions of picturesque landscape, but for the superior tonal rendition and atmospheric effects his prints displayed in comparison to local examples by other photographers such as Frederick Joyner.15

Kauffmann's status as an innovator was confirmed by his winning first and third prizes in the landscape category in the New South Wales Photographic Society's Intercolonial Exhibition in 1899. By 1901 his standing was such that he was invited to be a judge, alongside H.P. Gill, of the South Australian Photographic Society's annual exhibition, and to present his works in the invitation section.

The 1901 exhibition was the first in which awards were given, and it was hailed as one of the finest seen in Adelaide.

The reviewer for The Register claimed it as 'proof of the camera's recent advances', as 'some of the works could be mistaken for works of art due to the absence of all the hard and sharp lines usually associated with photography'. 16

The following year, the South Australian Photographic Society reached its zenith with an international exhibition in which Pictorial photography clearly dominated. Kauffmann exhibited fourteen carbon prints in the 1902 exhibition; they were duly praised in the newspaper reviews for their rendition of light and atmosphere.17

One of the new control processes, gum bichromate prints, was also evident in'the 1902 show. A reviewer found that those by the medal winner, David Blount of Scotland, were of 'an impressionist order, and while they are not calculated to please all tastes they have a value in their suggestiveness.' 18

This comment implies that a soft-focus impressionism was a distinctive feature of this show, whereas up until the turn of the century, Pictorialism in Australia had meant a mostly soft, picturesque view, still life or some form of a sentimental narrative. The promotion of a blatant soft-focus 'impressionist' imagery had appeared publicly as early as 1898, when Adelaide photographer, Fred Radford, published his article 'Impressionist Photography' in the Australasian Photo-Review, but does not seem to have been adopted until around 1902.

Radford argued that to be true to nature a photograph must have softness of outline, not overall sharpness; he urged amateurs to raise their sights above simple snapshooting.19 He restated the distinction that the art photographers felt they had over the mass of commercial or amateur hobbyists.

Within the wider art world, arguments for or against soft-focus effects and impressions had been well-rehearsed since the late 1880s.

Most famously, within Australian arts, the controversial 9 by 5 Impression Exhibition mounted by painters Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton and Charles Conder in Melbourne in 1889 had generated great debate.20 At the turn of the century, aesthetic debate in Kauffmann's home town of Adelaide centred on purchases for the Art Gallery of South Australia.

In 1900, to favour a style which was indistinct was a mark of progressiveness. In this year, Hallam, Lord Tennyson, Governor of South Australia, supported the purchases by the Gallery's honorary curator, H.P. Gill, under the Elder Bequest, when he argued for a soft naturalism or Whistler's type of 'colour-music ... You cannot minutely imitate and define everything in detail, for your picture would lack reality and life, since it would not give the mystery in which the universe is everywhere rapt.'21

Tennyson, however, was opposed to extremes of impressionism, which in his view were evidence of degeneracy. He collected Julia Margaret Cameron's blurry portraits and tableaux photographs illustrating the poetry of his father, Alfred, Lord Tennyson.

Emboldened by their success, the South Australian Photographic Society held an even larger international exhibition in 1903 which attracted more international entries than the year before. Horsley-Hinton and H.P. Robinson apparently both had prints on show. Recovering from its slump during the late 1890s, the New South Wales Photographic Society also mounted an international salon the same year, with gum bichromate prints by Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen in the special invitation section.

(The prints by Stieglitz and Steichen were on loan, not necessarily directly from the artists; at this time there appears to be no direct contact between Australians and the new Photo-Secession, although Stieglitz's publication for the Camera Club of New York, Camera Notes, was known to Alfred Joyner.22)

Kauffmann was among the medal winners in the Sydney exhibition, attracting the attention of the artist, Sydney Long; in his review of the show, Long noted that 'Mr Kauffmann s strong point seems to be the rendering of silvery light on masses of water.'23

There is no clear evidence that on his return to Adelaide in 1897 Kauffmann was using Radford's style of particularly exaggerated soft-focus. His adoption of such effects was more in line with overseas trends at the turn of the century, which he would have read about in photography journals. In the first few years of the new century the 'fuzzy wuzzies' were certainly at their height, and articles from many different quarters urged tolerance for those who were willing to open up their lenses.

The Australasian Photo-Review's editorial on the 1903 exhibition, however, sounded a note of derision, declaring: 'We notice many of our old friends from the fuzzy-wuzzy school, baffling the vision and confusing the brain of onlookers.'24 Jack Cato's sweeping accolade that Kauffmann's work alone inspired the South Australian Photographic Society 'to such efforts that in 1898 they held an exhibition which launched Pictorialism in this country, raised the whole standard of photography here to a new level, and influenced all future camera workers of Australia'25 is exaggerated.

However, Kauffmann and the South Australian Photographic Society certainly influenced Harold Cazneaux who, in 1952, recalled his conversion to art photography: I stood spellbound and inspired, here was a new beauty beyond anything I had dreamed of in terms of the camera. I was a young chap, a student at the Adelaide School of Design, in the year 1897. There I saw an Adelaide International Salon staged. I saw and decided that I too would be a Pictorial Photographer.26

|

| Harold Cazneaux Pyrmont Bridge (Sydney), c.1909 |

In the five years following his return to Adelaide, Kauffmann established a dominant profile within amateur photography. He had won medals before his return to Australia, and from 1900 was sending prints to annual overseas exhibitions and had work reproduced in the Photograms of the Year annuals.

Nothing is known of Kauffmann's life outside the salons during this period. His father died in 1901; his mother, with whom he resided, died in 1907. After this, Kauffmann moved to Melbourne, with the aid of his legacy. Presumably in these years Kauffmann had a darkroom at home.

His first professional studio listing occurs in 1917, at Scourfield Chambers, Level 2, 163 Collins Street, but he had either lived or worked from that address since 1912. On his arrival in Melbourne, Kauffmann sought out the Victorian Photographic Association, with whom he had exhibited and won medals in 1905.

In 1910, at the instigation of the Pictorialist, Henri Mallard, who was then the new manager of Harrington's Photosuppliers in Melbourne, the Victorian Photographic Association mounted a one-person show of Kauffmann's work in their rooms in Swanston Street.

|

| John Kauffmann Wharf labourers c.1910 half tone reproduction in The Art of John Kauffmann, 1919 |

| |

|

| John Kauffmann Melbourne Cup 1911 half tone reproduction in The Art of John Kauffmann, 1919 |

One-person shows were a novelty within the Australian art world in these years. Hans Heysen, the Adelaide painter, had held the first ever in Melbourne in 1909, and Harold Cazneaux mounted the first notable one-person show in photography in the same year.27 The Cazneaux show attracted commentary from the artists Sydney Ure Smith and Sydney Long.

Kauffmann's solo show was also well-reported in the journals and newspapers. Harrington's Photographic Journal devoted over one page to it, and the journal's regular reviewer, 'The Weevil', took up the argument for soft-focus: 'It is well known that in photographic circles, ever since photography became the means of pictorial expression, there has raged a controversy between what have been called, for want of better terms, the f64-ites 28and the fuzzy-wuzzies — inelegant terms for inelegant attitudes of mind.

Mr. Kauffmann's work showed that neither attitude is the correct one to adopt in contemplating the ideal in nature ... Here detail — softened though it may be — and the concentration of light calls unconscious attention to the beautiful part of the scene, while the less essential, though necessary, setting takes its unobtrusive place by suppression. Thus we get concentrated appreciation, the highest result of intellectual and aesthetic effort.'29

Other reviews praised this show and a later exhibition in 1914, also mounted by the Victorian Association. The 1914 exhibition travelled to Sydney, where it was shown in the New South Wales Photographic Society's rooms. Leslie Beer, then editor of Harrington's Photographic Journal, expressed some reservation regarding the dominant low tone and sombre mood of the works and their appropriateness to Australian conditions, but admired their 'dignified bigness'; he, along with other reviewers, stressed that Kauffmann was a 'true artist-photographer.

His specialty as shown in the prints on view is the depicting of subjects in a hazy atmosphere, producing a delightfully soft and realistic effect.'31 By 1914 Kauffmann's style included extreme examples of soft-focus. He was using a new miniature camera and isochromatic plates — thus the pictures were enlargements, which further softened the detail.

|

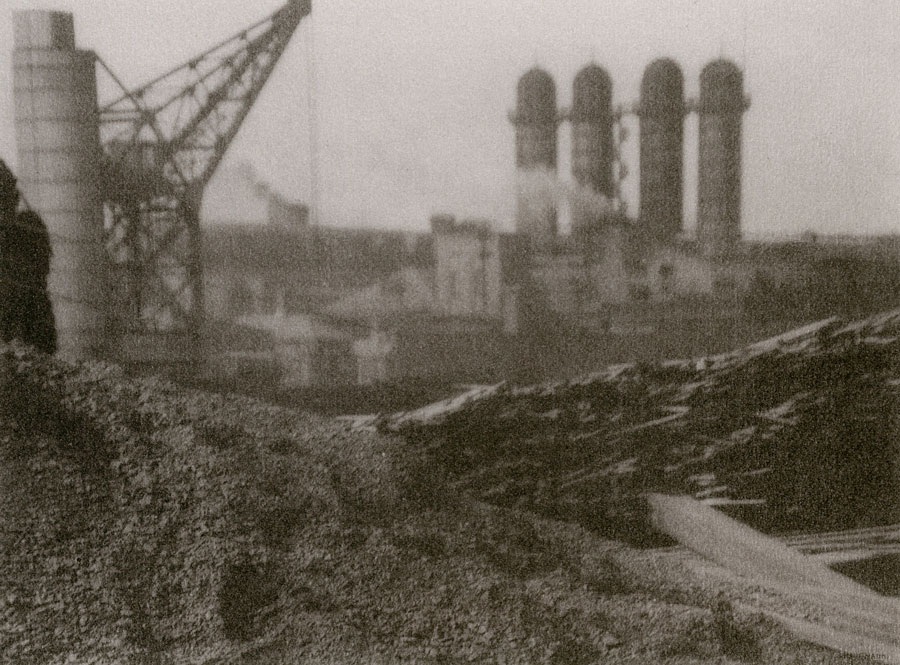

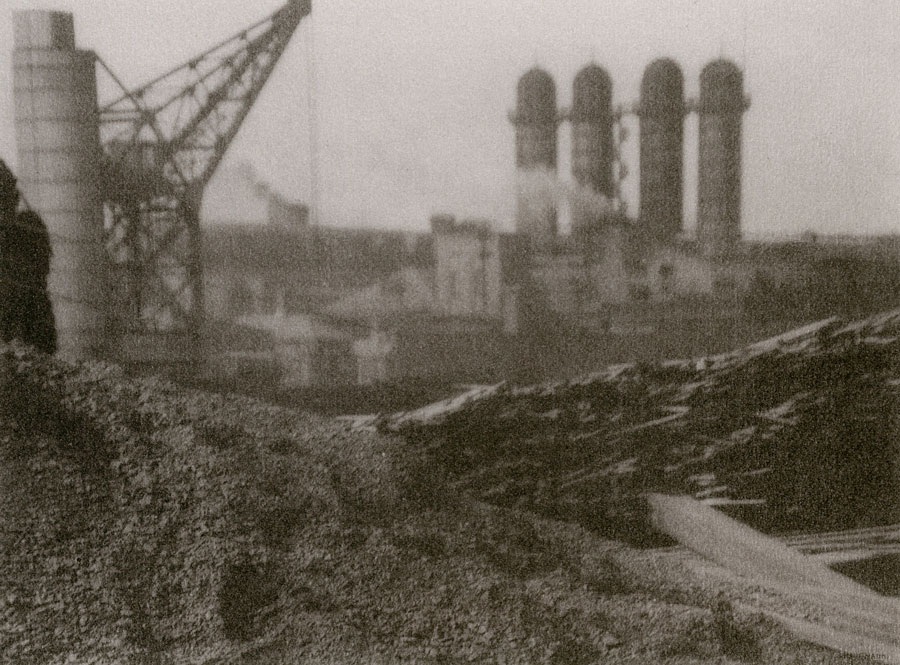

| John Kauffmann The gasworks c.1915 26.6 x 35.8 cm private collection |

The prints were mostly in the beautiful carbon process, with some gelatin silver photographs (then known as bromides). Stanley Eutrope, a young Pictorial photographer working in Melbourne at that time, recalled seeing crowds around some very fuzzy examples exhibited in Harrington's window. The prints were 10 guineas, a huge sum then; he thought they all sold.31

In the early years, Kauffmann had some success with portraiture and genre studies, but by 1914 he was known as a maker of landscape and urban images. People, if present in these later works, usually have their backs to the camera. Often the human element is absent. Pictorialists had a great fondness for the urban legacy of the Industrial Revolution. The gasworks c.1915 is a version of a traditional picturesque treatment of industry.

By the close of 1914 Australia was at war. Throughout World War I, art photographers continued their shows (the New South Wales Photographic Society holding its largest ever exhibition in 1917), although material shortages had their effect. Platinum paper could not be obtained from Germany and imported tissue for carbon prints was scarce.

Enlarging on bromide papers became common, and new processes, such as bromoil, gained ground. By 1920, the pre-war welter of manipulation processes and varieties of paper grades and surfaces available had permanently declined.

Despite his prominence in art photography, Kauffmann did not list his studio in the professional directories until 1917. He continued exhibiting, but the establishment of the Sydney Camera Circle in 1916, with its mission to escape the rut of impressionistic low tone, foreshadowed the shift away from the style and subject treatments in which Kauffmann excelled.

The new group was an elite band led by Harold Cazneaux; they claimed Australian sunshine as their inspiration. This was by no means the first call for sunlight to be the agent of national identity. Pragmatic recognition of the oddness of applying overtones of European mistiness to Australian scenery had accompanied Pictorialism at every stage of its development. War, however, gave the sunlight school the moral high ground, even if few Pictorial photographers went to war. Images from the Front were rare in the pages of the photographic journals during the war years. By the dawn of the 1920s, the cultural climate had changed.

The recognition of a need for more Australian subjects may account for the character of the monograph, The Art of John Kauffmann, published the year after hostilities ended. Its author, Leslie Beer, had overcome his reservations concerning Kauffmann's low tones.

The twenty works illustrated are predominantly treescapes and park scenes. Many had patriotic themes, suggested by titles such as Australian landscape, which had not been a feature of Kauffmann's earlier work. Other titles such as The battler and Victory (p. 49) reflected the post-war spirit.

The mighty gum tree had borne the standard of Australian nationalism since the 1888 centenary of settlement; after World War I, gum trees and the ti-tree (which was more frail in appearance) also stood as emblems of the fighters and the fallen. Enhanced nationalism focused more strongly on the gum, rather than European style woodlands and glens.

For Kauffmann, the coastal ti-trees provided a halfway point — they were Australian, but also had the character of the graceful wood forests he had photographed and drawn in Europe. Relatively few of Kauffmann's European works appeared in the monograph, with only a few figurative works and no portraits. Yet, in exhibitions in this period, he continued to reprint and show his most well-received European images, such as Winter mist (p. 57).

Kauffmann's pre-war prominence diminished after the war ended. The Sydney Camera Circle had captured the leadership of Australian Pictorialism and was enjoying considerable success in overseas salons and publications; activity was centred in Sydney. In 1924 Kauffmann was included in the Australian Salon of Photography in Sydney, the first ambitious post-war exhibition, but with only one work; and although he was a member of the committee of the succeeding exhibition in 1926, none of his works were included.

In the early 1930s his works were actually rejected by his local exhibiting body, the Victorian Salon. In 1934, Kauffmann complained to Cazneaux that 'Considering the time I have devoted to this movement and all the years I have devoted to it they should invite me to send in my prints with no selection to possibly throw them out. 32

In their writings both Cazneaux and Cato acknowledged Kauffmann's pioneering role but seemed to dismiss his body of work.

They saw him as old-fashioned in his own lifetime, less attuned to the spirit of Australian conditions than they themselves were. Cazneaux further commented that Kauffmann's decline 'is much the same as the "Great Stieglitz" of America: He too as he grew old gradually faded out of the picture.'33

Cazneaux's comparison of the two men's careers shows he knew little of Stieglitz's later role as a modernist.

Kauffmann was, in fact, quite active through the 1920s and 1930s. He even took on commercial work, doing fashion and some product advertising for Table Talk and The Home magazines — as did Cazneaux and other Pictorialists.

In the period of post-war economic growth, illustrated magazines provided a means of turning professional. By 1920 Cazneaux had his own professional practice as an elite studio portraitist, and was also working in commercial art as official photographer for The Home.

With strong encouragement from The Home's editors, Cazneaux blatantly updated his images to express a dynamic post-war nationalism and art deco modernist styling. Throughout the 1920s, Cazneaux's work was identified with the chic and modern lifestyle promoted by the magazines.34

Kauffmann's commercial work of the 1920s was merely competent, at a time when fashion and advertising photography was, in general, unimaginative and static. His personal aloofness and dislike of discussing business in any form may have hampered his professional dealings with hard-nosed editors.

In 1920 Kauffmann provided illustrations for a book on the Sunraysia district. In 1928 he provided twenty plates for the book Melbourne, a special number of Art in Australia; he was also given top billing as the photographer for the booklet, Melbourne, published by Sydney Ure Smith in 1931.

Cato and Cazneaux make little reference to Kauffmann's new work of the early 1930s. In general they suggest that it changed little and declined over time. In 1933, however, the writer and artist Ambrose Pratt wrote enthusiastically about Kauffmann's new body of work in an article in the Australian literary magazine, Manuscripts.

Pratt declared that Kauffmann's flower studies — apparently hardly known in Pictorial circles — were the images for which Kauffmann would be remembered.35 |

|

|

John Kauffmann Camera study

Ball and Welch georgette gown in the fashion supplement, The Home, 1 September, 1921 |

|

John Kauffmann A pioneer of the backblocks

photo illustration in The Sunraysia Wonder Book, published by the C.J. DeGaris Publishing House for the Australian Dried Fruits Association |

As with Cazneaux's work in this period, Kauffmann's close-up studies of flora and other subjects show an updating in the style of his images. The overall tonality in some is much brighter than in earlier works, and there is greater emphasis on design and form.

In 1935 Kauffmann held another one-person show. Significantly, the exhibition was not mounted by a photographic association, but was held at the Newman Galleries, Melbourne, and organised by an artists' agent, Mrs Edith Smart. It included a large selection of Kauffmann's later floral and still life studies. The show was well-attended and many works were sold.36

Although it was reviewed in the press, no reference was made to Kauffmann's development, and the exhibition was ignored by the photographic journals. Many works which appeal today — such as Pelican (p. 47) — do so perhaps because our perception is shaped by a streamlined modernist taste.

Kauffniann's floral studies show no reduction in quality from his earlier work. His concentration on them and the number of prints indicates he might have been planning a publication. In Europe at this time, modernist photography embraced the close-up; plants and flowers were popular subjects for demonstrating the order and form in nature.

Although Kauffniann's flower studies looked back to the unearthly beauties of the aestheticism of the turn of the century, their close-up form and design elements clearly indicate the widespread new style of the 1930s.

It is interesting to compare Kauffmann's atmospheric Sunlight thro'acanthus leaf and Edward Weston's contemporaneous Cabbage leaf of 1931 (regarded as one of the icons of modernist photography). There are certain points of rapport in vision in these works, alongside their fundamental technical and aesthetic differences.

Pictorialists would criticise Weston for his obsessive detail and lack of dominant motifs which, in their view, obscure understanding of the image. A modernist's perspective would be that Kauffniann's image is lacking in sensuous physicality, and fails to celebrate the unique qualities of camera vision.

|

|

|

| (above) Edward Weston Cabbage leaf 1931 |

(left) John Kauffmann Sunlight thro' acanthus leaf c.1930-35 |

Kauffmann's floral studies can also be compared with those of his younger contemporary, Olive Cotton.

Her well known Papyrus employs sharp angles of vision and a visual energy which Kauffmann perhaps would have not cared for; but there is similarity in their work. Cotton, schooled in Pictorialism but embracing modernism, mixed elements of both styles and approaches.37

Kauffmann also shared subjects and approaches with artists working in other mediums, especially with the lightly-painted oil studies of Clarice Beckett.

The rapport across all mediums at this time shows the unfairness of the dismissal by Kauffmann's peers of his later work.

Kauffmann's new works of this period were, however, those of an old man. By the late 1930s he was over seventy and had effectively retired from professional work. The advent of World War II probably put an end to most of his commercial activities. Perhaps his German surname made it difficult for him working in Australia during both world wars. |

|

|

| Olive Cotton Papyrus 1938 |

|

| John Kauffmann Design for frieze c.1920 |

Kauffmann's niece recalls how the floral studies he was working on when she knew him during 1939 to 1942 suited his lifestyle — he could walk to the Treasury Gardens at the end of the street in South Yarra where he lived without bothering with trains and buses.38 In his later years, Kauffmann continued to go to his studio in the city to print, and still took pupils.39 John Kauffmann died in November 1942. His last pupil was John Bilney who, in the 1970s, donated some of the first Kauffmann prints to be received in public collections.

No doubt Kauffmann's restriction of his subject matter to landscape and urban scenes accounts for much of the lack of interest in his work from 1920 until now. He did not seek the human interest 'narrative' which makes the work of the more popular Cazneaux so appealing. Yet the movement to which both belonged has attracted censure well into the present.

In 1982, photographer Max Dupain, as standard bearer for the modernists, went to the heart of their opposition to the Pictorialists:

There is quiet everywhere, trees probe the misty landscapes, children sit still, there is no haste, ladies present themselves elegantly and with grace, groups of people gather in somnolence, even the still lifes are very still indeed... There is no argument, no provocative social comment, no violence, no political slant, no rapid movement arrested in action, no strident industrial forms, no excruciating rendering of texture and detail so native to modern photography. We are in a world born of soft focus lenses and control printing processes... But it is fully competent, balanced, sensible, charming, eloquent and at the same time thoroughly right wing, conservative and sexless.40

Dupain's assumption that the values of his generation were aesthetically superior to those of his predecessors could equally be questioned by critics today.

Within the histories of art photography, the Pictorialists are often acknowledged for their promotion of photography as an art. Their images are widely dismissed as having no real place in the canon of important images and no legacy in the present. The commonality of Pictorial images is implicitly presented as inferior to the equally homogeneous works of the succeeding modernist style, with its detail, volume, pattern, sharp angles and contrasting lights.

For many, the dismissal of soft-focus over sharp is a moral issue, at the core of which lies the question: What makes a photograph a work of art?

|

| John Kauffmann Japanese magnolia c.1930-35 private collection |

Art Photographer contents page

Notes

- Jack Cato, The Story of the Camera in Australia, Melbourne: Georgian House, 1955, p. 149. Cato (1889-1971) was a leading portrait photographer in Melbourne from 1927-47 when he retired and concentrated on writing. From 1934 Cato's Collins Street studio was across the road from Kauffmann's studio; thus he could not claim thirty years acquaintance, and they were not friends. Cato relied on the 1919 monograph, The Art of John Kauffmann (see note 7), and on interviews with surviving associates for his information.

- Fellow photographer, John Scott Simmons, called Kauffmann 'the old roue', and Jack Cato's letters to Keast Burke indicate that he tried to interview Kauffmann's women friends. These friends were possibly Marie Gonard and Lucy Owens, who both received legacies under Kauffmann's will. In the late 1970s the author conducted interviews with a number of Kauffmann's associates: the photographers John Scott Simmons, John Bilney and Stanley Eutrope; as well as with Kauffmann's relatives: Mrs Pat McLeod, Mrs Diana Morton, Alex Marcus and Linda Philips. Copies of Kauffmann's will and interview notes held in the artist's file, National Gallery of Australia Research Library.

- In these years, Ruth Hollick, Mina Moore,Arthur Dickinson and Jack Cato were among the professional photographers with studios in the same area of Collins Street. All regularly advertised their studios and styles of portraiture. All used stylistic features of Pictorial art photography and exhibited their work in salons.

- Jack Cato, 1955, p. 149. In 1907, Kauffmann inherited some £500 from his mother — sufficient for a modest private income. His own will lists an estate of some £700 value, and further assets of approximately £300. No mention was made or value given to his photographs. A copy of the will is held in the Kauffmann file, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Australian National University, Canberra. Kauffmann also taught several pupils; Ina Jones, for example, reported on her lessons with Kauffmann to Harold Cazneaux, 27 August, 1929 (photocopy held in National Gallery of Australia Research Library).

- Jack Cato, 1955, p. 149.

- See Harold Cazneaux, 'Landscape Photography', in Oswald L. Ziegler (ed.), Australian Photography 1947, Sydney: Gotham, 1947, p. 13.

- Leslie Beer, in The Art of John Kauffmann: Twenty illustrations in half-tone with biography and essay by Leslie H. Beer, Melbourne: Alexander McCubbin, 1919, quote unsourced in unpaginated text. Leslie Beer was an artist and writer working in Sydney and Melbourne c.1900-25. He was in Paris in 1909. His watercolours were impressionistic in style. In 1914 he was editor of Harrington's Photographic Journal.

- Leslie Beer, 1919, implies that Kauffmann was studying to be an architect. From the naivete of his drawings in a surviving sketchbook (private collection), it is unlikely that Kauffmann was employed in any role other than a clerk. NB: The monograph spells Mackmurdo's name incorrectly — rather than Alexander Macmurdo [sic], it was Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo that Kauffmann worked for in London.

- Leslie Beer, 1919.

- Biographical details in Leslie Beer, 1919. The records of the Imperial and Royal Institute have not been located. Professor Josef Eder (1855-1944) was a major scientist and author of technical histories of photography and a member of the Vienna Camera Club. In 1889 he was appointed Director of the new Graphische Lehr-und Versuchsanstalt (presumably the Imperial and Royal Institute) in Vienna, which included instruction across the technical, artistic and photomechanical reproduction processes fields. He was the main developer of silver chloride bromide papers later used by Pictorialists. In courses run by Eder, Kauffmann would have had access to the most advanced photochemistry regarding exposure and printing of difficult tones and reflections, of great interest to Pictorialists. In the 1880s Alfred Stieglitz learnt similar skills in Berlin under another great photochemist, Professor Hermann (H.W.) Vogel. Germany and Austria were at this time the most advanced nations in the field of photochemistry and photomechanical reproduction processes. The Vienna Camera Club was a leading centre for Pictorial photography. Stieglitz toured Vienna in 1894, the same year Kauffmann was studying there.

- See report of South Australian Photographic Society in the Australian Photographic Journal, July, 1897, p. 174. Apart from exhibiting in their salons, Kauffmann did not involve himself in society activities nor, apparently, did he attend meetings.

- See Australian Photographic Journal, January 22, 1898, p. 22. The work was done and probably sponsored by the Austral Photo Works in Coburg, Victoria, established by Baker and Rouse Pty Ltd and later taken over by the Kodak company. The Australasian Photo-Review was established in 1894 and published out of the Baker and Rouse office in Adelaide; thus Kauffmann easily was able to bring his work to the company's attention. For a history of photographic papers in this period see Julie K. Brown, 'The Manufacture of Photographic Papers in Colonial Australia 1890-1900', History of Photography, vol. 12, no. 4, October - December, 1988, pp. 345-355.

- The notes in the catalogue of the New South Wales Society of Artists annual exhibition, November 1897, made special mention of the opening up of eligible exhibits to the graphic arts of poster work and design. The Australian Star, 8 October, 1897, p. 2.

- The Australian Star, 8 October, 1897, p. 2,and the Australasian Photo-Review, 20 October, 1897, p. 28.

- For the role of Kauffmann's contemporaries, in particular Frederick Joyner, see Jean Waterhouse and Alison Carroll, Real Visions: The life and work ofF.A. Joyner, South Australian photographer 1863-1945, Adelaide: Art Gallery of South Australia, 1981. Joyner was a most active promoter of Pictorial photography, and one of its best local exponents. He owned one of Kauffmann's European scenes, A field of snow, now held by Michael Treloar, Adelaide.

- The Register, 19 October, 1901, p. 7.

- The Adelaide Observer, 27 September, 1902, p. 14.

- Ibid. The reviewer was T. Helens.

- Fred T. Radford, 'Impressionist Photography', Australasian Photo-Review, 24 August, 1899, pp. 9-10. Radford was the proprietor of Friihlings Studio in Adelaide; he exhibited impressionistic works until around 1912.

- See particularly Ann Galbally's 'Aestheticism in Australia', in A. Bradley and T. Smith (eds), Australian Art and Architecture: Essays presented to Bernard Smith, Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1980, pp. 124-129.

- Elder Pictures', The Adelaide Observer, 14 April, 1900, p. 15. Hallam, Lord Tennyson (1852-1928) was the eldest son of the Poet Laureate; he came to Australia in 1889 as Governor of South Australia

- Jean Waterhouse and Alison Carroll, 1981, p. 3.

- Sid [sic] Long, 'An Artist's Summing Up, of the Pictures Exhibited at the NSW Photographic Society Exhibition', Australasian Photo-Review, December 21, 1903, pp. 442-450.

- Editorial, Australasian Photo-Review, 21 December, 1903, p. 440.

- Jack Cato, 1955, p. 149.

- Letters from Cazneaux to Jack Cato, ms, April, 1952 (photocopies held by National Gallery of Australia Research Library).

- In 1919, The Art of John Kauffmann incorrectly claimed Kauffmann's as the first one-person show in Australian photography.

- Literally the technical term for the maximum narrowing of the aperture on the lens of a camera. Use of a wide open lens gave a very soft focus overall and a narrow zone of detail.

- See review by The Weevil, 'Mr Kauffmann's One Man Show', Harrington's Photographic Journal, December 22, 1910, pp. 375-381. Also reviewed by The Argus, 18 November, 1910, p. 8.

- Leslie Beer's editorial, Harrington's Photographic Journal, 22 April, 1914, p. 134. However, the sombreness of the work did not impress him.

- A selection of the prints was also displayed in the window of Harrington's Photosuppliers in Adelaide between May and June 1914. Stanley Eutrope's comments from an interview with the author, 1979 (copy held by National Gallery of Australia Research Library).

- Reported verbatim by Harold Cazneaux, in letter no. 13 to Jack Cato, mid-1951, p. 1 (photocopy of ms held by the National Gallery of Australia Research Library).

- Ibid.

- See Robert Holden, Cover Up — The art of magazine covers in Australia, Australia and New Zealand: Hodder and Stoughton, 1995.

- Ambrose Pratt, 'The Art of John Kauffmann', Manuscripts: A miscellany of art and letters, Geelong, Victoria, no. 7, November, 1933, pp. 31-34.

- Mrs Edith Smart's career is unknown outside this work as a freelance art dealer. She reported on the sales and attendance (600) to Harold Cazneaux, who had written to her for information on Kauffmann for his reports to the Photograms of the Year journal. Letter to Cazneaux, 11 April, 1935,3 pp (photocopy held by the National Gallery of Australia Research Library).

- Helen Ennis, Olive Cotton: Photographer, Canberra: National Library of Australia, 1995.

- Letter from Mrs Pat McLeod to the author, 1 July, 1979, p. 3 (copy held by the National Gallery of Australia Research Library).

- One young photographer, Edward Cranstone (later known for his documentary work during World War II) spent a year with Kauffmann in 1935. Cranstone had no money for lessons, but Kauffmann let him use the studio anyway, and Cranstone gained a solid grounding in printing techniques.

- This quote is from page 2 of the typescript of a speech delivered by Max Dupain at the Australian opening of Pictorial Photography in Britain 1900-1920, an exhibition first mounted by the Arts Council of Great Britain in 1978. It toured to Australia, opening at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, 15 March, 1982 (copy of speech held by the National Gallery of Australia Research Library).

Art Photographer- main page

or return to John Kauffmann special page

|