Landscape and Photographers

a historical perspective

Gael Newton AM

Editted version of article originally published landscape australia february 2004

Looking at the evolution of specialist photographers of the built environment and landscape since the 19th century reveals more than technical changes and the visual archaeology of sites - it is a way to understand changing attitudes to the environment.

Photographers from the first decades in the 1840s to 1860s gave priority to construction and the pride colonists took in their civic progress. Their views are dominated by instruments for the taming of the environment such as bridges - or if in an urban setting - the civilizing of colonial life by fine streetscapes, parks and gardens.

Views of nature and the landscape were not taken much for their beauty per se but as part of fact-finding missions about botany or geology being gathered for future economic application or development of the area.

|

| Charles Bayliss |

Major professional photographers of the earlier wet-plate era like Charles Nettleton in Melbourne, Charles Bayliss in Sydney, and George Freeman in Adelaide, were great technicians. They learnt how and when to take images which meticulously recorded every stanchion and finial and gave substance to the self-image of the colonists.

However, because their cameras and plates could not show much movement or cloud detail in the sky, the spaces in mid-19th century photographs can appear artificial like a model or stage set. Sometimes the contrast between grandiose stone façades in the style of older European cities and the still unpaved road or grazing animals in the backyard subverts the efforts to instantly 'age' and aggrandise their environments.

The popular image of early Victorians as stiff and artificial owes much to the nature of the photographic records they left. One of the great photographic undertakings of the period was the record of the New South Wales western goldfield towns as well as the new metropolises of Sydney and Melbourne undertaken for German-born mine owner and businessman B.O. Holtermann, by photographers Beaufoy Merlin and Charles Bayliss in the 1870s and 80s.

|

| Beaufoy Merlin |

Of the thousands of negatives produced and prints exhibited few were interested in the natural environment. Less common in early photographs was evidence of any aesthetic appreciation of the character of the Australian landscape for its own sake. If people are present they are often directed to stand in different planes within the image but rarely with any appearance of being at home in the place.

By the late 1870s, the new dry-plate allowed for easier excursions for the photographer who did not have to take a wet-plate kit and dark-tent along. Plates became faster and more sensitive and people could be shown on the move.

As the exploration and pastoral era was closing and being overtaken by urban development, a number of city photographers found that they could specialise in picturesque landscape work leaving behind the endless parades of top hats, crinolines and fractious babies of the studio portrait trade. Masters of the grand architectural and engineering view tended not to follow the new path.

The new roving landscape photographers work reflected the growth in recreational use of the landscape as families settled in suburbs, the native born generations increased and more and more workers were employed in offices and factories than on the land.

People from all classes used the new railway networks for day trips and holidays from which they brought home photographs as souvenirs and inducements to taking to the great outdoors. 'Lifestyle', might be the buzz-word of the 1990s on - but the concept goes way-back.

The destruction of wilderness accompanying urbanisation was also already apparent by the mid-19th century leading to the emergence of conservation and environmental movements.

As the turn of the century approached the era of the Kodak and easy amateur photography made for a repertoire of more natural looking images and records of actual activities and lifestyles. The professionals had to keep up by capturing the new naturalism in their imagery.

Henry King essentially a poet of the city and harbourside in Sydney in the 1880s and 90s in particular captured a new relaxed feel to his work with stylish design to his images and lively action.

|

| Nicholas Caire |

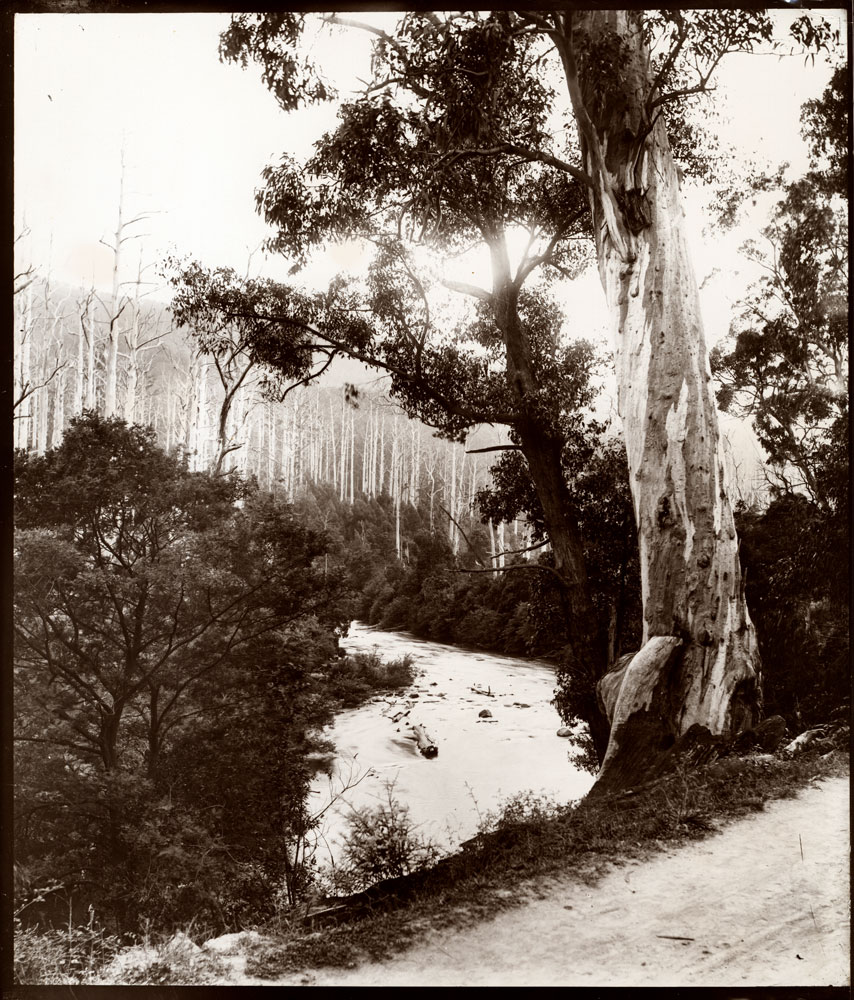

Nicolas Caire, J.W. Lindt and J.W. Beattie are especially interesting as landscape and environmental photographers in the late 19th century because they also promoted the appreciation and preservation of the distinctive natural world in Australia.

Nicolas Caire, who came to South Australia in1858 became one of the finest landscape photographers in 19th century Australia. He began his working life as a hairdresser which is rather fitting; shaping a natural outgrowth on the head may be not so different from shaping nature into picturesque images in the camera.

Caire who finally settled in Melbourne was one of the first to specialise in landscape and build a business in the late 1870s on the rustic 'ferny dell' and bushland vision of Australia.

As the country approached the centenary of European settlement in 1888, the fern tree was seen as the leitmotiv upon which a genuine Australian art and architecture might be built rather than imported. Caire made a particular study of the giant trees of Victoria, argued for their preservation and also held views about the necessity of bush walking and healthy living.

While Nicolas Caire despaired over the loss of the tree giants and undertook camping trips for health as well as photographic activity he had it seems no particular close connection with architects or landscape designers.

His friend, John William Lindt however, was not only a fellow promoter of 'Australia the beautiful’ and health giving bush recreational experiences but made it his lifestyle.

Lindt had immigrated from Germany in 1862 settling first in New South Wales at Grafton where in the early 1870s photographed aboriginal people in the area in rustic 'native' tableaux elaborately set up in his studio. He exported his pints often in portfolios, in large numbers worldwide.

The 'natural' however, was always to be staged and presented as a museum diorama. It was Lindt's experiences as a photographer attached to an expedition to New Guinea in1885 which formed his vision of living 'in' nature.

In 1894 after weathering the depression in Victoria, Lindt closed his city studio in Melbourne and moved to thirty-two hectares of land at the top of a ridge of the Dandenongs. There he built a home, studio and guesthouse he called 'The Hermitage' - meaning a retreat - but perhaps also a reference to European romantic landscape architects practise of placing a hermit's cave among the grounds of a rural estate.

While appreciating the native bush Lindt designed his property as a European alpine-eyrie with extensive foreign specimens especially of fir-trees. The Hermitage was a kind of ‘nature’ theme park which included elevated walkways and treetop viewing platforms derived from models he had seen in his New Guinea travels.

The site is much diminished today although the hydrangeas have gone feral quite nicely. It is still worth the effort to visit but first check with the present owners and arm yourself with original images so as to imagine what it was.

When John Muir, the pioneer of conservation in America made a world tour of giant trees in 1903, he visited Caire but also what he called 'Lindtland'. According to Tim Bonyhady in his book The colonial earth,* Muir's visit inspired a flurry of publication by both photographers on the giant trees of Victoria and scenic delights of the region.

In Tasmania, John Watt Beattie an immigrant from Scotland in 1878 also specialised in images of the landscape. From the 1880s on he became a keen promoter of tourism but also actively campaigning for preservation of large areas as wilderness including the Gordon River.

Stephen Spurling III who was born in Hobart in 1876 came from a line of photographers and became one of the first and most energetic photographers to visit the remote wilderness regions of Tasmania.

Both Beattie and Spurling did a range of work but their dedication to landscape as a genre prefigures the specific role and character of wilderness photographers of the 1940s-1990s in Tasmania.

The 19th and early 20th pioneer photographers depending on their inclination celebrated the built and unbuilt.

After the turn of the century the new breed of art photographers like Harold Cazneaux sought to create gently romantic views of a tamed bush pastoral in their works. A later generation from the 1930s such as Max Dupain on adopted modernist and documentary styles of photography.

They brought to their work a different sense of national identity and the 'genius' of place searching for what was unique or characteristic in detail, light and patterns.

Interestingly, a number of landscape and built environment photographers have 'walked the talk' so to speak by creating for themselves fine homes in natural settings like Lindt.

Cazneaux's house at Roseville called 'Ambleside' had a lush cottage garden in the manner of Edna Walling.

Frank Hurley, who is best known for his Antarctic expeditions work, devoted the last decades or so of his career to a series of publications on Australia in which he extolled both progress and appreciation of the pastoral scene and native bush. Hurley created for himself a series of fine mixed native and foreign fauna gardens around Sydney concluding with a property on a cliff top above Narrabeen Lakes in Sydney.

Twentieth century architectural and landscape photographers Max Dupain, David Moore (both now deceased) and Richard Woldendorp today in Western Australia, have created beautiful bushland homes as a flow on from their creative imaging of the land and environment.

Wesley Stacey whose archive of colonial and vernacular architecture and Australia-wide environmental photographs dates back to the 1960s, opted to live when not travelling in his van, in a tent on his property on the south coast of New South Wales.

To date a sense of what is a specialist 'landscape architecture photographer' does not exist with the same clarity as the genres of architectural/ industrial or wilderness photographer. Like landscape architecture the actual tradition exists long before the professional terminology.

* Tim Bonyhady, The colonial earth (Miegunyah Press, MUP, Melbourne: 2000)

more of Gael Newton's Essays and Articles

|