AUCTION AUTOPSY

The Mossgreen Dupain Estate Sales 2016-17

Gael Newton

21 June 2017

Monday last I was glued from 10.30 am (they give us a lunch break) till dusk to the live feed of the second and final Mossgreen Max Dupain Estate sale from the collection of artist-son Rex Dupain (other large collections are held by family).

I wasn't bidding but advising a few people and noting patterns of buying for cultural gifts valuations. By 6.00 pm I was saddle-sore and crick-necked from looking to screen then turning to the catalogue to make 600 notations.

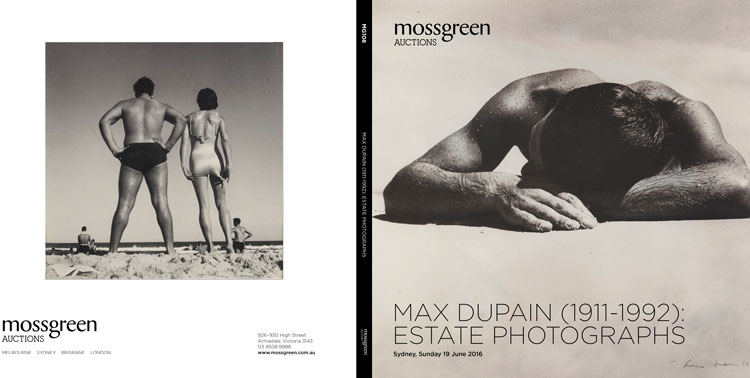

The previous March I had been invited to say a few words at the preview of Mossgreen’s much publicised Max Dupain Estate auction, that came with a brick of an illustrated catalogue. The first show with 497 works had been an amazing opportunity to encompass the life work of the artist in more or less one go. It was quite exciting even in concept, as no photographic artist had ever been given the full star treatment in the art market in Australia.

The advantage of a multiple art medium such as photography that has never seen a collecting frenzy, was that so much work was still available. The Mossgreen show had lots of icons such as the 1938 Sunbaker but also hundreds of unfamiliar works including a few I had never seen.

An update on the Sunbaker: Dr Shaune Lakin, Senior Curator, Photography at the National Gallery of Australia has recently nailed the date to January 1938 or after – that’s a separate story of super sleuthing.

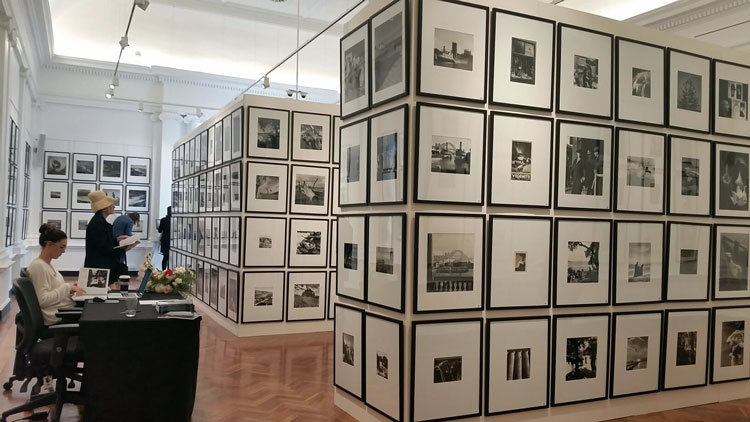

Walking into the firm’s newly renovated Victorian era premises in Queen street in June 2016, I was faced with floor to ceiling black and white photographs (well in truth pre WWII vintage prints are more coffee on clotted cream paper) in black wood frames with crisp white mounts. There were more upstairs on the stairwell, the upper gallery the staff offices and maybe even the loos.

The logistics and economics of the photography, and cataloguing, matting and framing was quite stunning - and a big gamble.

The preview also a launch of the Sydney Mossgreen premises, was packed. It was a quite glamorous social event and there was a strong sense that people who had never bought a photograph were going to try to get a Dupain. A handful of serious money collectors were ready to secure as many icons as possible or to take the long view and opportunity to build a significant collection that could never be assembled for any other major artist without decades of acquisitions.

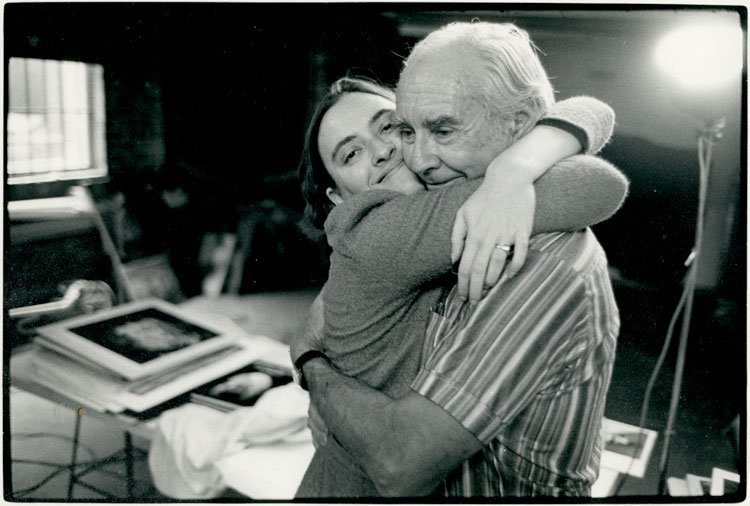

What was extraordinary for me was that because of the stacked ‘salon hang’ as it is known, I could take in the whole of life achievement of an artist I knew very well. I had done the first museum Dupain retrospective at the Art Gallery of New South Wales and the first scholarly monograph in 1980. I considered Max a friend. He took a series of fab glam portraits of me in 1980 in my office and in 1982 with my first baby. [see - Irreverance A gloss upon the smile].

What ruthlessly culled curated shows or edited publications don't give is anything like the experience of standing in a room with hundreds of pictures seeing connections and almost hearing conversations between images made fifty or so years apart.

So if you missed the two auctions, the experience cant be imagined.

Sadly I didn’t see the second installation except in friend’s snaps.

below - 3 images of the 2016 Max Dupain auction

below - an image of the 2017 Max Dupain auction

By the time I gave my speech at the initial June 2016 preview, I was calling for the return of salon hangs that used to feature in 19th and early 20th pre modern exhibitions. There were close to a thousand prints for sale in the two auctions (there are large family holdings in private hands).

What also struck me was that Dupain maintained the vitalist rage that motivated his work until the end.

It was a matter of his spiritual survival.

The first auction had on the whole large prints and it occurred to me that there can't have been that many exhibitions in his lifetime to match the level of printing. Max did exhibit from the 30s to 70s in the old style camera society salons, photographic illustrators exhibitions and other commissioned presentations. In the 1980s fine art exhibitions and art print sales became a dominant part of the studio output.

Yet somehow there were more prints than could ever have been exhibited. He made these because he wasn't a photojournalist he had to print to make the work.

Dupain also undertook many new series in the 70-s 80s including still life studies and flower pieces. A number were subtly or overtly surrealist – the movement that facilitated his artistic breakthrough in 1935. One was an elegiac set of images of the head of Aphrodite off a figurine belonging to his father, being tossed in and out on the tide breaking on a beach probably at Newport where his had parents lived.

These had nothing to do with commercial jobs. They are the least appreciated works as Dupain’s national role has become the visual definer of Australia. His documentary work from the 30s—40s representing an imagined more cohesive white Australian past.

The Dupain auctions were of a lifetime of making remarkably sustained powerful and engaged works of art. This was not always my view. In truth, when I was doing the 1980 retrospective I was not focussed on Dupain’s postwar work, such as the late industrial works and a lot of the architecture he loved as well as outback shots made while working on corporate commissions.

One of the joys of having curatorial positions as long as I have is that you have the time and opportunities to reassess former views of artworks. It is very exciting to see things differently and to realise that you may have missed something earlier.

At the time my concentration was elsewhere as I was motivated to retrieve his significance as a modernist with a surrealist bent in the 1930s and 40s. He was after-all the first Australian artist to respond to surrealism in 1935 - something I suspect some art historians have trouble admitting to.

The postwar works now seem to me to be gems and others obviously agreed on the day.

At both auctions all types flew out the door. It was clear that there were buyers who went for the overlooked works and landscapes that once they are home on the wall and given the spot light, will glow. I even detected at the June 2017auction that Mossgreen founder and CEO Paul Sumner who led the auctioneering, repeatedly said ‘nice print ‘lovely image’ about a number of quieter works. I’m not cynical – it was not a ploy – he saw what was there.

So now that I am not institutionalised I don't have to be bureaucratically measured or careful. I can say the experience seeing the work at the auction house was fantastic. I think Dupain did great deeply and intuitively felt work that actually has meaning for Australians. Shame we do such a lousy job promoting our artists past or present overseas.

A little number crunching. The June 2016 auction had a bigger core of well known key early works including a large Sunbaker that went for a record for an Australian photograph of AUS$105,000 and the sale grossed AUS$1.67 million.

I’ve no idea what that means in terms or return to the vendor versus the house but the house costs must have been considerable.

When I tabulated the results (in the 2016 auction) it was interesting that only some 15 works went for above AUS$10,000 and 30 odd or so above AUS$5,000.

In the June 2017 auction fewer went for more than AUS$5,000, the bulk went for a few hundred to a few thousand and that was with a mat and a frame. That’s about the same in today’s money as what they were when first made.

The Dupain studio negatives are now all united in the Mitchell Library and a digitization program is in hand. This will serve legions of scholars in future of Australian life and landscape (and a glimpse of wartime New Guinea, 1980s Fiji and Vanuatu) admirably. The strong bones of Dupain’s composition survive reprinting by library appointees but the depth of Dupain the artist is located in the vintage prints.

The Mossgreen auctions and online record will serve as essential future references to the Dupain oeuvre - grab both catalogues if you can - who knows if the online versions will be there in 50 years.

Let us hope that all auction house records and dealer gallery end up in a public archive.

Gael Newton

Photo credits:

1 Photograph at Max's studio of Max and myself by my dear friend Robert McFarlane

2 Gael Newton, 1980, by Max Dupain (one of several treasured photographs of myself taken by Max)

3 Mossgreen's Max Dupain exhibition for their auction 2016 - 3 photos by Paul Costigan

4 Mossgreen's Max Dupain exhibition for the auction 2017 - photo by Belinda Hungerford

more Essays and Articles

|