*The 2018 online version of Gael Newton's essay originally published

in the catalogue for Singapore's Asian Civilization Museum's Catalogue

for the Port Cities 2016 exhibition; more on the exhibition below this article

From Java I will most likely go to Borneo and from there to Manilla to China and then to India, that is if I live so long. I shall be able to write a voyage around the world when I arrive home.

Walter B, Woodbury, a British photographer, on preparing to depart in May 1857 from work on the Australian goldfields for a world tour in search of fresh opportunities. He got no further than the Dutch East Indies, where he founded the long running firm of Woodbury & Page in 1857.

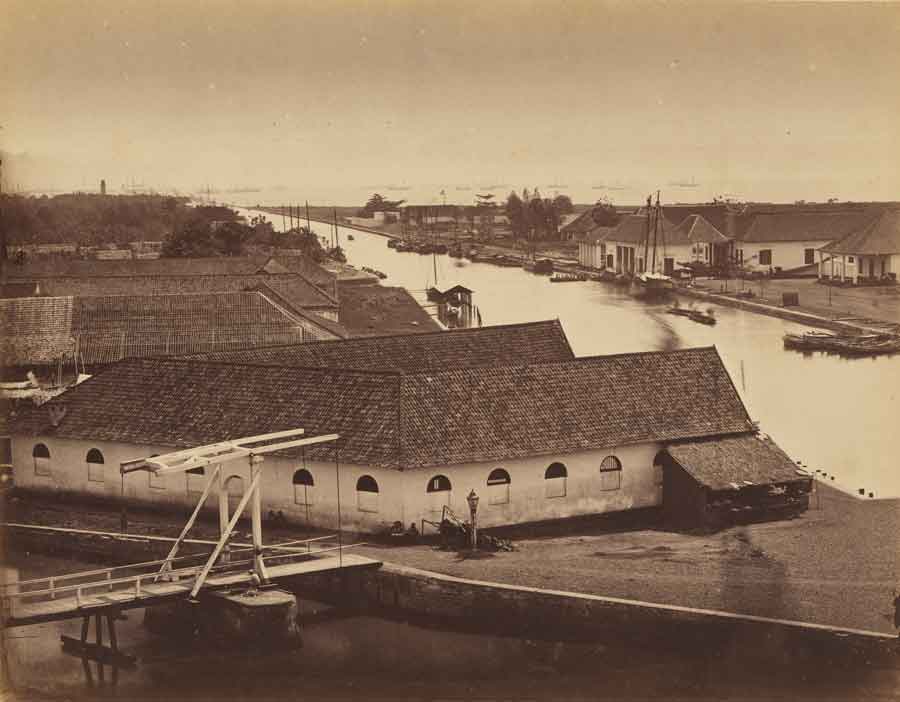

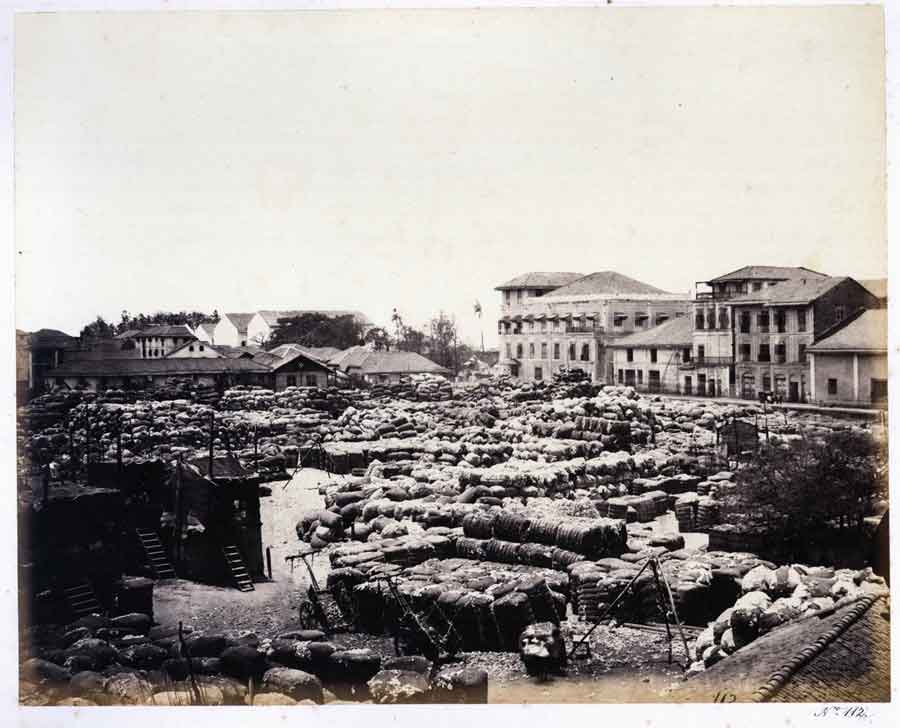

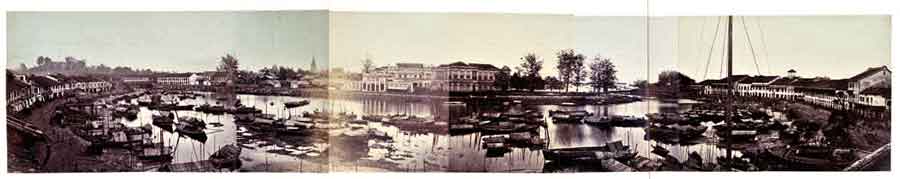

Woodbury ran it with two of his brothers until the 1880s, and they made the largest and most widely distributed nineteenth-century images of colonial-era Indonesia. (fig.1)1

Fig 1: Woodbury & Page, Batavia roadstead, around 1865. Albumen photograph, 19.4 x 24.5. National Gallery of Australia.

Ships had to anchor in the "roadstead" offshore. In 1857, photographers Walter Woodbury and James Page and their baggage arrived by a flat-bottomed lighter at this dock in the Harbour Canal.

Photography ships out

On 8 December 1839, the Paris journal la caricature published a cartoon by Theodore Maurisset titled la daguerreotupomanie, which satirized the recent craze for the photography process perfected by a well-known painter and the owner-designer of diorama shows in Paris and London, J, L, M, Daguerre (1787-1851). Only months before, the French government had bought Daguerre's patent for producing highly detailed mirror-like images on polished metal plates, and gifted the technical secrets "free to the world" on 19 August, Daguerre's marketing campaign over 1838 and 1839 had whipped up such anticipation that by the time the method was revealed, the world was wild for photography.

Each daguerreotype was unique and needed to be cased to protect its vulnerable surface, A rival British process on paper called "photogenic drawing" was released by W, H, F, Talbot (1800-1877) in January 1839. This was a method for making impressions of objects on sensitized paper by direct contact or photographic images via a camera lens, and was open to amateurs to attempt. It was easier and cheaper to make but less detailed and not quite as dramatic a performance as seeing a daguerreotype plate develop.The daguerreotype promised to deliver the world in miniature - albeit without colour or action.

In Maurisset's image we see swirling crowds of fashionable Parisians seeking all manner of photographic experiences while out of work artists are shown committing suicide in despair. Trains and steam ships loaded up with cameras can be seen in the background of La daguerreotypomanie. In the foreground a jolly young gent in black suit carries a daguerreotype camera, tripod, and chemicals (fig. 2), captioned as his "appareil portatif pour le voyage" (traveller's portable camera outfit), under his arm, and Daguerre's manual of instructions tucked in his pocket.

|

|

|

Fig 2: Theodore Maurisset. La daguerreotypomanie (detail of plate on pp. 43-44). From La caricature (1839) - click on image to see full cartoon |

|

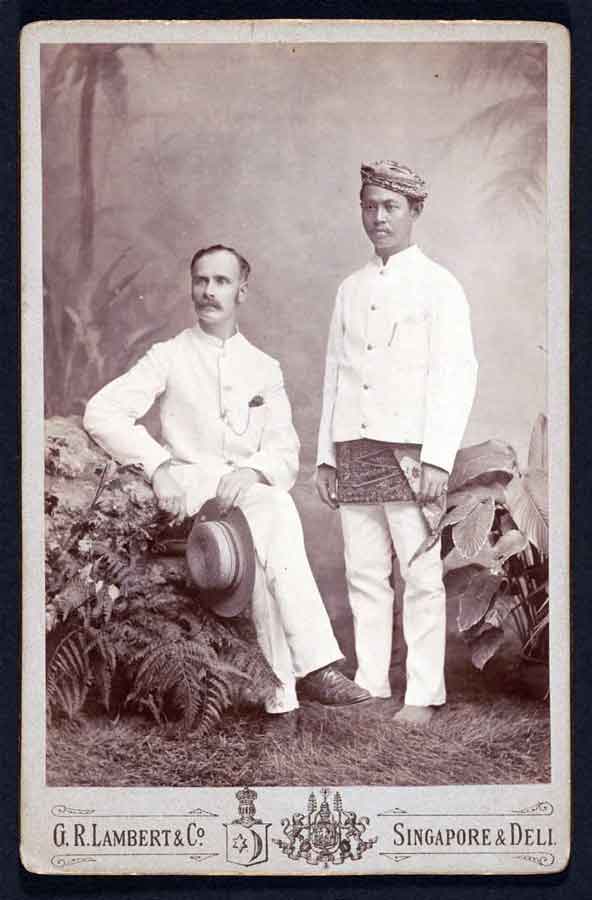

Fig 3: G, R, Lambert & Co, Singapore & Delhi. William Hancock, Chinese Maritime Customs Service official, posing with unidentified man, Sumatra, January 1891. Albumen photograph, 17x11 cm Edward Bangs Drew Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University. |

This is probably the first-ever depiction of a travelling photographer, Maurisset was not fantasizing: photography was on the move. Expensive Daguerre-Giroux brand cameras had been dispatched on a world cruise via South America in September, and the Paris optician N, R Lerebours was marketing a cheaper apparatus by October.

In the first half-century or so of photography, several hundred such men, mostly from Europe, would take photography to the port cities of Asia in the hopes of making their fortune (fig. 3). Some swapped their black suits for the all-white suiting adopted by foreign residents in Asia. Their arrival inspired both foreign residents and native-born to take up photography as hobby or profession.

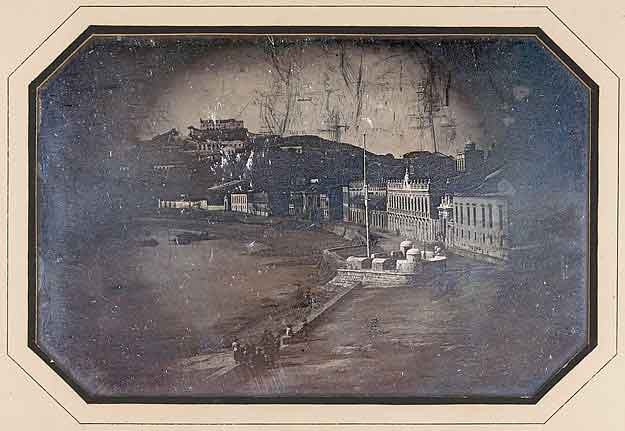

The first Asian photographers would arise in the port cities,2 The earliest photographs surviving photographs of Asia and Asians are in the daguerreotypes of 1844 by French trade negotiator Jules Itier (fig. 4).

|

Fig 4: Jules Itier. Vue redressee de la Praia á Macao, Octobre 1844.

Daguerreotype, 9,3 x 14,3 cm Musee français de la Photographie, Biévres |

Photography makes port

In January 1840 a daguerreotype camera was advertised by Thacker and Company in Calcutta, the earliest known sale in Asia. The instrument was possibly the one used by Irish physician, pharmacologist, and inventor Dr William O'Shaughnessy (1808-1889) in February to make daguerreotypes. The doctor had already made photogenic drawings in October the previous year. By the end of the year British trade firms in Calcutta included six employees listed as "artist, photographer".3

Dr O'Shaughnessy's efforts are the earliest known success in making photographs in Asia. He may have experimented a year or so later with Talbot's superior calotype process of 1841, which allowed for multiple printing of photographic images on paper using a paper negative. The watercolour paper used for the process resulted in a more graphic image than the fine detail and tonal range of the daguerreotype. Portraiture was not possible at this time due to the need for excruciating long exposures.

The great advantage of the paper process was that it enabled mass production of prints. The calotype would prove markedly popular in British India in the 1850s, particularly for recording antiquities, but was rarely used elsewhere in Asia. The first photographic images travelled back along the seaways to Europe as soon as they were made, and were often publically exhibited.

There was no means to reproduce photographs in the press until the 1880s, but redrawn as engravings and lithographs, the new imagery educated the international public and at the same time fixed stereotyped perceptions of Asia which linger into the present day.4

The photographers of mid–to late nineteenth-century Asia followed the patterns set in the previous century by itinerant painters from Europe who went East in search of sales and commissions. Portuguese, Dutch, and British artists in particular sought out the Asian colonial possessions of their nations but the field was open to all.

Some would never return, ending their days in far-distant ports – such as the Prussian-born Jacob Janssen (1779-1856), who left home in 1807, and travelled via Copenhagen, Lisbon, and Boston then studied with an Italian artist in Philadelphia.

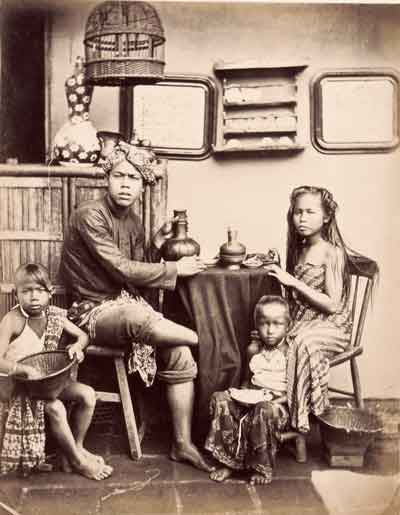

Janssen worked chiefly as a topographical artist in Rio de Janeiro, Calcutta, Singapore, and Manila in the 1830s before settling in Sydney in 1840. Janssen's generation of travelling artists soon faced competition from itinerant and local photographic artists. For example, the Dutch-Flemish engraver and opera singer Isidore van Kinsbergen (1821-1905), who arrived in Batavia in 1851 with a French Opera Company and stayed on to become a pioneer photographer in the 1850s (fig. 5) and theatre director in his later years.5 |

|

|

| |

Fig 5: Isidore van Kinsbergen. Malay family, around 1865. Albumen silver photograph,195x15.2cm, National Museum of Singapore [2011-00701-028]

click on image to enlarge

|

Asia on a metal plate and paper pages

Despite Maurisset's accurate description of the instant export of cameras and photographers, there was no Parisian-style daguerreotypomanie in any of Asia's port cities. Indeed there are scant references even to the very first accounts of the invention of photography around 1840 in foreign-language colonial papers.

This lack obscures how effectively travellers on fast ships brought the latest news out of Europe within a few months. By the time cameras or photographers arrived there was no need to explain what photography was. Local newspapers and published reports, while few, show that by the mid-1840s daguerreotype activity of some sort had happened in most of the major Asian ports.

Eyewitness reports of first sightings of photographs being made in Asia are rare.6 A number of visiting naval expeditions to Asia in the 1840s had cameras aboard, but nothing is known of their use. The 1849 autobiography of Malacca-born Indian munshi Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, a teacher of Malay and translator in Singapore, recorded seeing a doctor from an American warship make a daguerreotype view of Singapore between mid-1840 and 1841.7

Remarkably, two caches of daguerreotypes from Southeast Asia survive: one from a French trade negotiator and amateur photographer Jules Itier and the other by Adolph Schaefer, one of the first generation of professional photographers at work in Asia (figs. 6, 8).

| |

|

|

| |

Fig 6: Jules Itier. Vue de la villa á commerce a Singapour, 1844. Daguerrotype, 12,6 x 15 cm National Museum of Singapore [2005-00445] |

|

Jules Itier (1802-1877) was a well-educated administrator with scientific and natural history interests. He travelled in Asia for two years as chief commercial negotiator on the French government legation sent to China to conclude the first Franco-Chinese trade agreement signed at Whampoa in October 1844.

While in Singapore, the French Legation stayed at the London Hotel of Gaston Dutronquoy, who hailed from French-speaking Guernsey in the Channel Islands, Dutronquoy was part-showman. He had a theatre on the premises and had advertised a daguerreotype portrait service in December 1843 and January 1844. Self-taught, Dutronquoy seems not to have succeeded with his photographic venture and must have viewed Itier's successful plates with not a little envy.

On his journey, Itier succeeded in making his first Asian views and portraits in Singapore, then in Guangzhou, Macau, Manila, Saigon, as well as Galle in Sri Lanka, on the way home.8

These are the earliest extant photographic images from these lands. Itier's own account, Journal d'un uoyage en Chine en 1843, 1844, 1845, 1846 (published in Paris between from 1848 to 1853), reveals his curiosity about plants and people, and describes some of his photographic operations. Itier was undaunted by the difficulties of securing portraits. His surviving plates include people in the street, Europeans, and the first known portraits of Chinese sitters.

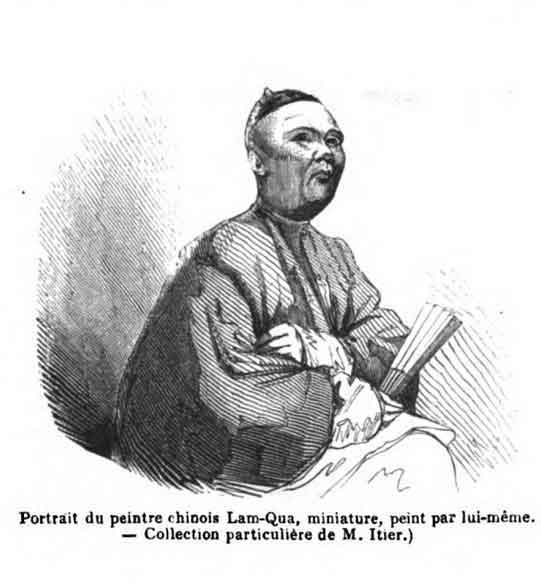

Most revealing is the exchange Itier reported of his photographing Lam Qua (1801-1860), a renowned painter servicing the foreign community in Guangzhou. Lam Qua was a master of Western academic realist oil painting who had exhibited at the Royal Academy in London. He was keen to see the "admirable apparatus that can draw by itself and that so intrigued the painters of Canton". He sat for a daguerreotype portrait and then a few days later presented Itier with a painted miniature copy of the daguerreotype as a memento, which Itier exhibited with his own plates on his return to France in 1847 (fig. 7).9

|

|

|

Fig 7: Portrait of Chinese painter Lam Qua, miniature painted by himself. Print, Collection de M, Itier in L’Illustrations Journal universel, no, 182, vol. 7 (22 August 1846) p. 393, Hathi Trust and University of California Libraries. |

|

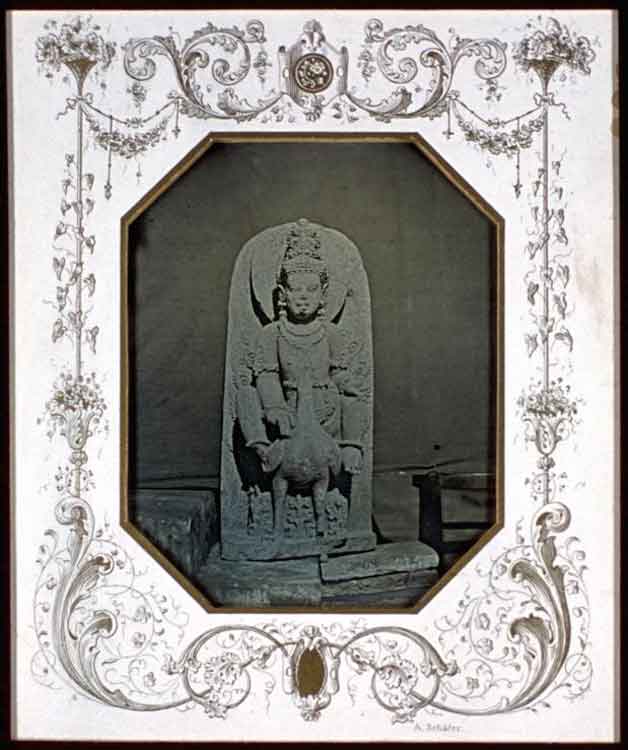

Fig 8: Adolpf Schaefer, Sculpture of Hindu god Karttikeya, 1845Daguerrotype. Leiden University Library. |

Itier used some of his own plates as the basis for illustrations in his own publication but did not circulate his works more widely. His archive remained in the family home in southern France unseen until its rediscovery in the 1980s. But even at the tiny scale and murkiness, in his daguerrotypes there is a vivid sense of what the place and people actually looked like, with which no print or painting can compare.10

The first instance of government-commissioned photography in the Asia was not in British India, as might be expected from the early interest of the new medium, but in 1841 at the instruction of the Dutch Ministry of Colonies in Amsterdam. They equipped medical officer Jurriaan Munnich (1817-1865) to test out the process in the tropics. Unfortunately his results were not satisfactory.

The longer-term object of the Ministry of Colonies had been to see if the antiquities, especially the Borobudur complex in central Java, could be photographed. In 1843 they agreed to advance funds for better equipment for a second attempt by German professional Adolph Schaefer. The Jauasche Courant of 22 February 1845 reported on his "beautiful and numerous" portraits, which had ended the "despair that Daguerre's art could ever be exercised fully in the tropics".

Schaefer succeeded too in photographing Borobudur in 1845. A magnificent set of daguerreotypes of Borobudur and of antiquities in the Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences collection were sent back to the Netherlands but little used. Schaefer stayed on in Asia but was bankrupt by 1849. The Leiden University library holds his plates (fig. 8).11

Another significant route for the transmission of the daguerreotype into southern Asia was via the Pacific. During the 1850s, numerous daguerreian artists trained or came to Asia via North America. They moved form port to port as there were not enough customers to stay put. New arrivals tended to advertise that they had the latest American refinements, indicating a general rise in the perception of American technological know-how. This was possibly because daguerreotypes had a poor reputation, and were thought to fade and deteriorate in tropical conditions.

Most daguerreotypists worked for short periods, made only modest incomes, and left little personal trace. One who we do know about through his memoir Resemlnnen fran Sodra och Norra Amerlka, Aslen och Afrlka (published in Stockholm in 1886) is Swedish adventure-traveller Cesar von Duben (1819-1888). He set out in 1843 for lands he had read about as a child and returned home in 1858.

Already a competent draughtsman, Duben took up photography in Philadelphia in 1849, practised in Mexico, America, China, the Philippines, Hong Kong, Singapore, Burma, India, and Indonesia.

While many failed, Duben successfully used photography for a decade to support himself (fig. 9). Duben's reminiscences, along with Itier'sjournal, are the only personal glimpses of contact with locals by daguerreotype photographers in Southeast Asia.12

We will never know how happy residents in the port cities were with their metal plate images as so few portrait daguerreotypes survive. However, the arrival of the new paper photographs in the late 1850s turned a trickle of images made in Asia into a tide that flowed not only from port to port but also back into Europe and America.

The wet-plate process gave superior clarity of detail and when paired with brilliantly detailed albumen (egg white printing papers), provided the means for photographic images and photographers to multiply and circulate worldwide.

It was this process that would create the visual heritage of nineteenth-century photography of the people and places of the port cities of Asia.

The wet-plate process allowed for easier and cheaper portraiture, and for the production of views for sale. Advertisements bristle with claims of the superiority of the new paper prints, and offer large arrays of formats from stereographs and bound albums to the modest-priced small portraits on card mounts known as cartes de ulsltes that could be collected into albums.

Soon studios were offering prints of the people, the city, and surroundings for pasting into albums. For convenience, studios also had their own albums. Within a decade, locals and visitors alike could easily and relatively cheaply insert their own images into the new travel and family albums alongside professional views from home and abroad. |

|

|

| |

Fig 9: Cesar Duben. Prest van Madras, plate after original daguerrotype of around 1855. Photolithograph in Reseminnen fran Sodra och Norra Amerika. Asien och Afrika (Stockholm 1886) National Gallery of Australia Research Library |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

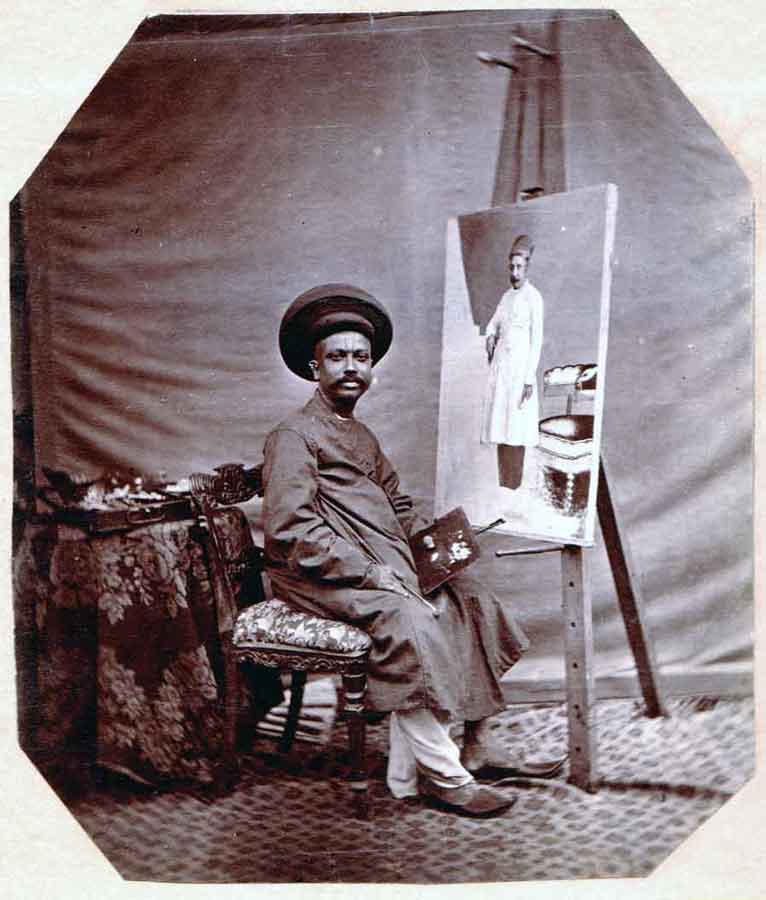

Fig 10: Hurrichand Chintamon. Self portrait as a painter in Bombay, around 1860. Albumen photograph Collection Hugh Ashley Rayner, Bath |

The novelties of the era were showpiece panoramas, but these were expensive, had relatively few buyers, and could only be made by the best photographers.

Photographers could now compete with the established styles and genres of the graphic arts but with the added value that their images showed what the places and people actually looked like. The wet-plate era would also preserve the work of the first Asian-born photographers, and in several rare cases, their self-portraits. The latter include a suave self-portrait as a painter, showing the fascinating Hindu professional Hurrichand Chintamon in Bombay (Mumbai) around 1865 (fig. 10).

Bombay masterworks on paper

In the 1850s and 1860s, British India provided the most fertile ground for early photography on paper, to judge by the number of enthusiasts. The most remarkable figure in early paper photography in South and Southeast Asia was the German artist-lithographer Frederick Fiebig, who was based in Calcutta in the 1840s. He took up calotype photography around 1849 and made hundreds of images in Calcutta, Chennai, and Sri Lanka in the early 1850s (fig. 11).

|

Fig 11: Frederik Feibig. Dwelling of an English gentleman [Garden Reach]. Calcutta, around 1851.

Hand-coloured, salted paper photograph British Library

|

Fiebig made a practice of hand-colouring many of his prints. When Fiebig sold the East India Company in London some five hundred prints in 1856, he told the directors of how "during my travels in India I employed my leisure time in taking photographic views of the principal buildings and other places of interest at Calcutta, Madras, the Coromandel Coast, Ceylon, Mauritius, and the Cape of Good Hope".13 His output was over a thousand prints, a huge collection to have assembled in such hot climates in three or four years. Photography in the field was not for the faint-hearted in the formative decades of the medium in Asia.

Fiebig's focus was on the comforting vision of the white, neoclassical buildings of the British Corporation and missionaries taking a rightful place alongside the past glory of ancient Hindu and Islamic antiquities. The photographer's challenges compared to the artist are apparent in Fiebig's charming scenes. The photographer has to undertake artistic posing, arranging people and other objects, before making his image. The photographer cannot compile his scene at leisure from various life sketches.

Fiebig's images have a characteristic array of carefully positioned Indian figures dispersed throughout the space. No matter how hard they try to avoid it, there is often a person who does not follow direction and is caught clearly looking at the camera. That is the charm of the abundance of extras that come with the photographic view.

Fiebig's photographs show the messier reality of Calcutta and the jostle of new and dilapidated in the port, His visit to Madras in 1852 was reported in Illustrated Indian Journal of Arts in February 1852, While local artists were grateful to have had lessons in the useful process, the reviewer warned that photography was a "dangerous aid to the artist, as it teaches him to regard nature too much in her everyday common garb, when she is in general common place, vulgar, and minute," This warning did little to discourage local photographers, particularly among the East India Company's technical ranks, Fiebig's East India Company collection survives in the British Library.14

In the 1850s and 60s, East India Company officers undertook extensive journeys beyond the ports, recording the Mughal, Hindu, and Buddhist antiquities of India. They exhibited their works in various locations locally and internationally. Back in port, practitioners of the new medium usually belonged to one of the photographic societies that were the first to be formed anywhere outside Europe.

The Calcutta society, founded in 1854, had two hundred members, both Indian and foreign, by 1858. A Bombay society was formed in 1855 and the one in Madras followed in 1856.

The officer class of amateur photographers tended to favour antiquities. One of the earliest and most elegant applications of photography on paper in the Asian ports was initiated in the mid-1850s on the lively metropolis of Bombay, by William Johnson and William Henderson. They were founder members of the Bombay Photographic Society. Both were East India Company civil servants who parlayed their amateur interest into professional practice.

Johnson had arrived in Bombay by 1848 and worked as a clerk. He opened a daguerreotype studio in 1852, but shifted to the wet-plate by 1854. Johnson was a founder and secretary, and oversaw the society's monthly issues of the Indian Amateur's Photographic Album, with three original prints per issue. Henderson had begun work as a Military Board Office clerk in 1840, and was in partnership with Johnson from 1857 to 1859, then in his own business until 1866.

Johnson and Henderson compiled some of the first published albums in Asia: their Costumes and Characters of Western India and Photographs of Western India appeared between 1855 and 1862. This album included a three-panel panorama of Calcutta from Saint Thomas Cathedral (made around 1855 and measuring 20 by 78 cm) - one of the earliest in this format in Asia. The large format and rich tones of the wet-plate photographs enabled a real panorama of scenes and images of the many races and cultures (fig. 12). The prints had a veracity of raw detail that drew on all the established genres of topographical views, and occupation and costume studies. Above all else the photographs powerfully captured a sense of the activity on the docks, in particular the Parsee merchants involved in the cotton trade. Not all the images in the published albums were by Johnson or Henderson.

|

Fig 12: William Johnson. The cotton ground, Colaba, Bombay, around 1858.

Albumen photograph Photographs of Western India, Volume II. Scenery, Public Buildings, &c

19 x 24 cm National Gallery of Australia

|

In his 1863 book on Bombay, Mumbaiche Varnan, Goan writer Govind Narayan (1815-1865) gave an early description of the craze for photography among British and Indian residents. He noted: "There are thirty to forty men who can produce such pictures. Many youths have mastered this process and have established workshops in their houses to capture the images of their near and dear ones". He picked out Dr Narayan Daji Lad and Harischandra (Hurrichand) Chintamon as experts among the Hindus, and William Johnson as the most famous among the British. He noted that Johnson planned to present his series of men and women of the castes of Bombay to "the Empress", that is, Gueen Victoria.15

In that very year, Johnson was in London publishing his two-volume The Oriental Races and Tribes, Residents and Visitors of Bombay (1863, 1866). It is the earliest ethnographic publication in Asia to be illustrated with photographs.

|

|

From nothing in the mid-1840s, within a decade, hundreds of large-format photographic prints documented the urban character and social structure of India. British residents are not included in these "types", but private albums and official portraits were also creating a record of this class.

The Oriental Races and Tribes, Residents and Visitors of Bombay sought to convey the racial diversity of India's most populous city, and is a tour de force of montages of studio portraits matched with appropriate outdoor shots of urban, domestic, or rural scenes, including proud Rajput princes, Brahmin, Muslim, and Parsee men and women.

The Johnson and Henderson images included both the usual types and also a good cross-section of ethno-religious groups, including Goan Catholics, or "Portuguese Christians", seen with males in Western suits and the women in Goan-style saris who had immigrated to Bombay by the 1850s (fig.13).

Their Western-influenced education and experience of higher caste Hindu and Goan Catholics in the Portuguese colonial administration led to significant roles in teaching English and Latin, as well as service in the British navy as seamen or musicians on the expanding commercial shipping lines. |

Fig 13: William Johnson. Goanese Christians, around 1855-62. Albumen silver photograph, no, 23 in The Oriental Races and Tribes, Residents and Visitors of Bombay: A Series of Photographs with Letter-Press Descriptions by William Johnson Bombay Civil Service (uncov), London, 1863 DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas |

|

|

Fig 14: William Johnson and William Henderson. Vallabháchárya Mahárájas, 1856.

The Oriental Races and Tribes, Residents and Visitors of Bombay: A Series of Photographs with Letter-press Descriptions by William Johnson Bombay Civil Service (uncov), no, 23, vl, "Gujarat, Kutch. and Kathiawar", London,1863

Albumen silver photograph, letterpress on card, 26 x 18 cm National Gallery of Australia

|

One Goan Christian was Dr Narayan Daji Lad (1828-1875), the first Indian faculty member at Grant Medical College, who had a long career as a photographer in Bombay, including tours with the governor of Bombay. He and his brother Dr Bhau Daji Lad were active in the cultural and political life of Bombay, including organisations such as the Photographic Society. Narayan complained in the press about Johnson's piracy of his images, such as the photograph of Vallabhacharya Maharajas in Oriental Races and Tribes (fig.14).

Another photograph in Johnson's album appears to be by Hurrichund Chintamon, who ran the first Indian professional studio in Bombay. Chintamon is an intriguing character yet to be studied in depth. He lived in England for periods from 1874 to the 1880s, as an agent for the Gaekwad of Baroda, and devoted much time to spiritual matters, including for the Theosophy movement.16 The Johnson and Henderson portfolios remain impressive over a century and a half later.

Whether Johnson was responsible for the montage work is not known. It possibly inspired a later catalogue of all Indian races that John Forbes Watson and John William Kaye compiled - an eight-volume study with over four hundred photographs of different castes and races entitled The People of India, which appeared between 1868 and 1875. The feel of the two projects is not comparable: the latter being a utilitarian directory of castes, while a sense of a vibrant multiracial, multi-faith community exists in the Johnson tome.

By the early 1860s, a new generation of wet-plate view and portrait photographers were setting up across the network of Southeast Asian ports. As Johnson departed for London, his countryman Samuel Bourne, an ambitious amateur photographer turned professional from Norfolk in England, arrived. He had been a clerk but had determined to come to India and make his name with landscape and topographic photography. He formed a partnership with Charles Shepherd, and their firm Bourne and Shepherd would become one of the major distributors of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Indian imagery.

Bourne's great achievement was his Himalayan journeys in the 1860s, but the firm also presented panoramic visions of the gleaming English colonial architecture of the port cities (fig.15).

While providing views for sale, most photographers also made portraits and house calls at fine homes, creating a less visible record of private life, including in some cases for elite Indian customers.

|

Fig 15: Samuel Bourne. Calcutta. Panoramic view from Ochlerlony Monument.

Prince of Wales Tour of India 1875-6 (vol,3), 1863-76. Albumen print, Royal Collection Trust [RCIN 2701702]

Click on image to enlarge

|

Expanded views

One of the first of the new wet-plate firms to arrive in Java in 1857 was the partnership of Walter B, Woodbury (1834-1885) and James Page. The pair had started their partnership in the Australian goldfields during 1855-57, but found that there was far too much competition. They gave up hopes of a permanent studio in Melbourne and planned to travel from port to port and end up in Valparaiso.

On arrival in Batavia, however, they were delighted to find that there were only three other photographers. With the superior technique offered by the wet-plate cartes and the luscious cased photographs on glass called ambrotypes, they were besieged by an extraordinary variety of customers. The clientele included, as Walter wrote home to his mother in 1858, "part Dutch Chinese Malay half casts, Maduresse Bandanese Arabs countesses, chevaliers Javanese and a variety of others."

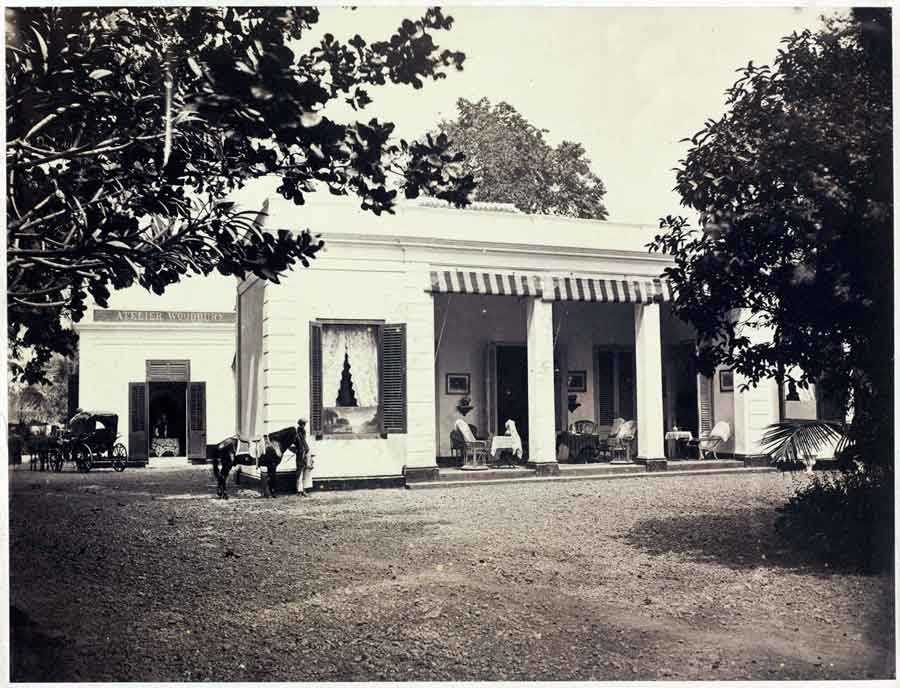

Woodbury established a charming suburban home and a purpose-built studio in Batavia (fig.16). He organized extensive excursions to the sites of antiquities such as Borobodur, but also started the first sale of images of Malay and Chinese types, and of the sultans of central Java and their exotic dancers.

|

Fig 16: Woodbury and Page. Woodbury and Page studio in Batavia.

Albumen photograph KITLV (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Carribbean Studies), Amsterdam

|

| |

|

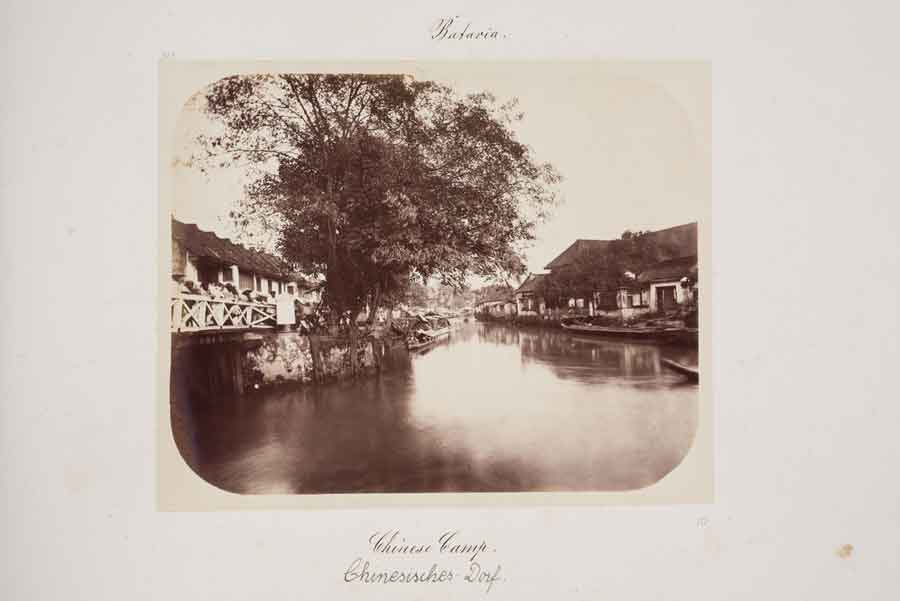

Fig 17: Woodbury & Page. Chinese Quarter, around 1866. Albumen photograph National Museum of Singapore [2008-05831-010]

The Chinese were required to live just outside the south gate of the city, in an area that became known as Glodok.

Today, Glodok is the centre of Jakarta's Chinatow.n

|

The Chinese quarter fascinated Woodbury and proved popular as a subject throughout the firm's long operations into the 1880s. He sold stereographs of these subjects to London opticians and publishers Negretti and Zambra in 1861 (fig.17). Woodbury and Page brought out the first album of views of Batavia in 1864, and sold distinctive albums packaged in portfolios labelled Vues de Jaua for decades, Page died early of a tropical fever and Walter returned home in 1863 to fame as the inventor of the Woodburytype, having set up his firm to continue under brothers Henry and then Albert.

Until its decline in the late 1880s, Woodbury and Page and the army of native assistants and other operators, such as Henry Schuren who went on to play a significant role in Bangkok and Manila in the 1870s, produced thousands of beautifully toned, highly detailed, elegantly composed images that remain well-represented in most overseas archives.

When he arrived in Batavia, Woodbury made no mention of one of the other established photographers. Isidore van Kinsbergen (1821-1905), the Belgian-Flemish artist, theatre performer, and singer, made a name for himself in the 1860s and 1870s photographing the ancient monuments of Java. These photographs were exhibited widely.

He also made dramatic tableaux of royalty and natives that were much used in late nineteenth-century publications. Kinsbergen was a true immigrant: he lived a long life in Java and was deeply involved in the foreign community. His tableaux portraits and figure studies have a certain theatrical flair but also demonstrate his connection with his sitters.

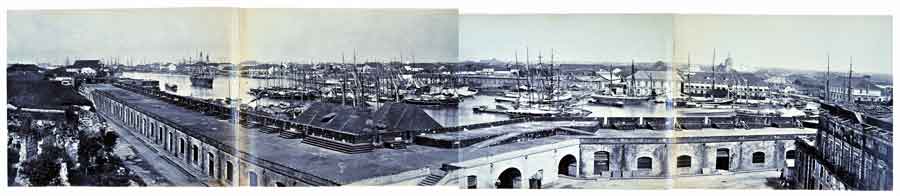

The same 1860s patterns can be seen in the Straits Settlements, where the Austrian August Sachtler, who had a substantial career in an Austrian government expedition to Japan in the early 1860s, arrived with his brother Carl Herman and opened a studio in Singapore in 1862. He also worked with the Dane Kristen Feilberg (1839-1919), who ran their Penang branch. The Sachtlers were the first studio in Singapore, and made the earliest panoramas of the city in 1863, where both died in 1874 after a decade of successful operation (fig.18).

|

Fig 18: Attributed to Sachtler & Co.

Boat Quay on Singapore River, Court House under Renovation. Harbour Master's Office and Town Hall around 1874.

Four panel panorama on successive pages of a French travel album assembled around 1885; albumen photographs Musee Guimet, Paris

Click on image to enlarge

|

Like Woodbury and Page and Bourne and Shepherd, the Sachtlers used a base in one port to make photographic expeditions to nearby regions to build inventories. August Sachtler and Feilberg made the first album of views of Singapore, and images of the cultural mix of peoples, referred to as "types", along with the first albums of Sarawak. Feilberg produced impressive, mammoth plates of the wild, unknown regions and of the Batak peoples in Sumatra.

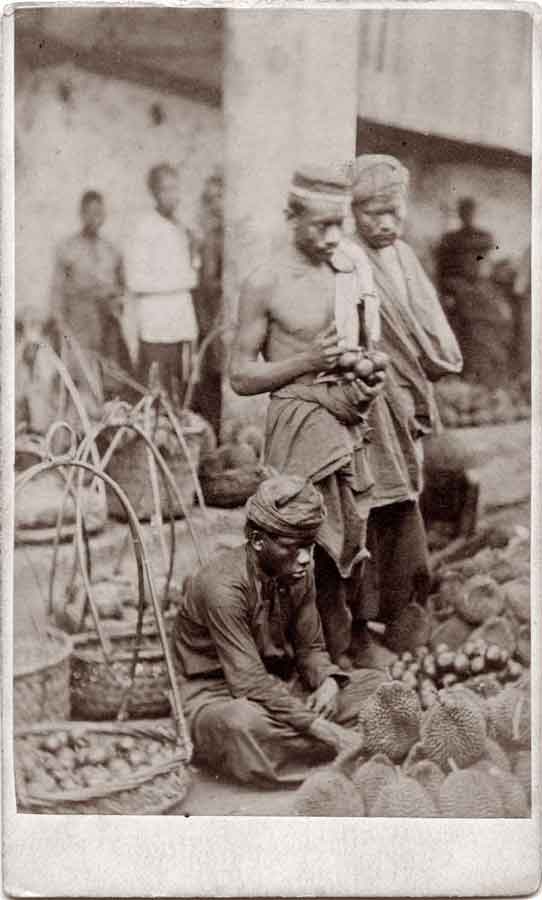

The Scottish photographer John Thomson, who started up in Singapore in 1863 also branched out by working in Penang for ten months to capitalize on a more exotic, older port. He found his true calling as an outdoor photographer on the streets of Penang. Thomson's technical ability allowed him to present his subjects, as in his Durian sellers (fig.19). with some sense of naturalness.

Through this engagement with the locals, Thomson more or less invented the idea of the "travel photographer" as a social reporter rather than merely a merchant of souvenirs. Thomson pioneered the modern model of a photojournalist in the 1870s with the publication of his four-volume Illustrations of China and Its People: A Series of Two Hundred Photographs (London, 1873-74), using the autotype process.17 |

|

|

| |

Fig 19: John Thomson. Malays selling durians, Singapore or Penang 1862.

Albumen photograph, carte de visite, Photoweb collection |

By the mid-1860s, there were established studios in most major Asian ports who sent their operators out on the streets and offshore, and into the hinterlands for views and native types. These photographs were marketed in the ports and also sent abroad for armchair travellers, as well as for publication.

While most studios in Southeast Asia were run by European photographers, in India, Hong Kong, and Java, Asian photographers set up studios catering to both European and indigenous clients. For example, Afong and Pun Lun in Hong Kong had studios of their own by the 1860s, Pun Lun operated as well in Singapore and Shanghai.

By the 1880s, in the main port city centres, a few larger enterprises grew to become veritable palaces of photography.18 These had showrooms hung salon-style floor to ceiling with almost life-sized portraits in heavy wood frames, along with cases of accessories offering multiple choices everything from massive albums to miniature lockets. Going to the right photographer for one's social set became a factor. These patterns continued on into the early twentieth century, with packaged tour groups visiting studios to buy souvenirs and postcards.

The most singularly elaborate and far-reaching enterprise was that of the German professional Gustave Lambert (1846-1907), who established his long-running firm in Singapore in 1877.19 By the 1890s, it had a building decorated with a fancy portico on Orchard Road, as well as a studio in the centre of the city, Lambert served as official photographer to the king of Siam, and his studio cards were emblazoned with medals won at international exhibitions, Branches were set up in Deli, Sumatra, while numerous operators, mostly from Middle Europe, began or passed though the Lambert and Company,

Like Woodbury and Page, who always stamped their work, G, R, Lambert and Company maintained strict quality control, and consequently their prints are usually easily identified through their rich tone, detail, and assured composition. Alexander Koch became owner-manager after Lambert's return to Germany in 1885, and he developed an inventory of some three thousand views of Southeast Asia, including what amounts to a racial atlas of the region.

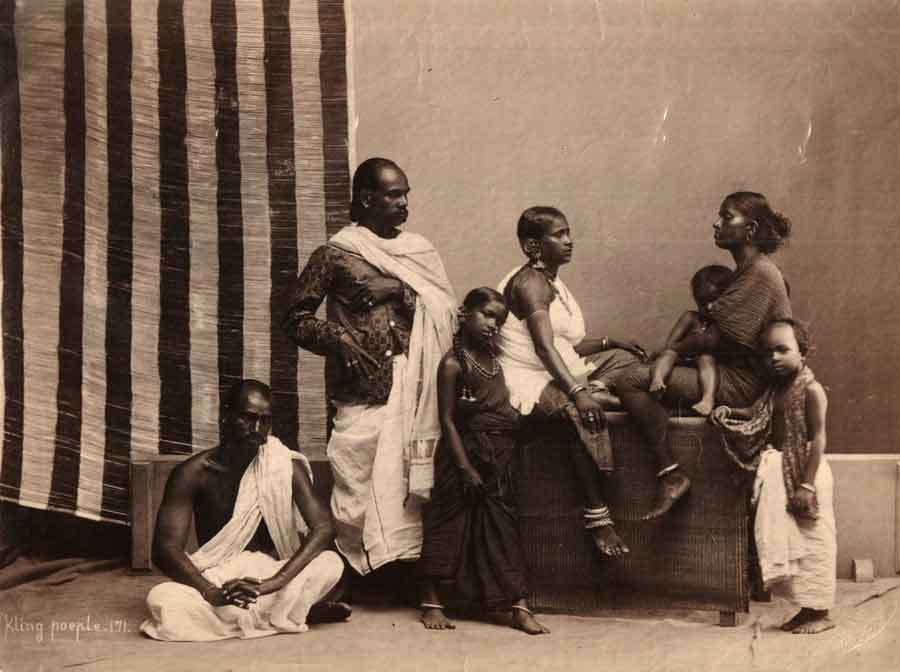

|

Fig 20: Rudolf Jasperacher, photographer. G,R, Lambert & Co Kling family. 1886-88.

Albumen photograph Private collection

|

| |

|

Fig 21: Premises of Ohnnes Kurkdjian, Surabaya. 1910. Gelatin silver photograph,

KITLV (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Carribbean Studies), Amsterdam

|

| |

Images from Sumatra and remoter regions were probably made in those locations, but Singapore's many races provided enough Kling, Chinese, Malay, Thai, and mixed-race sitters, who were set up with minimal props (fig. 20). Unlike William Johnson, little effort was expended on appropriate backdrops.

In Surabaya, the firm of Armenian Ohnnes Kurkdjian (1851-1903) dominated the tourist image of Java until well into the 1930s (fig. 21). For a generation of travellers, readers, and collectors worldwide, the output of these major firms defined the tropics and the cultural images of the peoples of South and Southeast Asia.

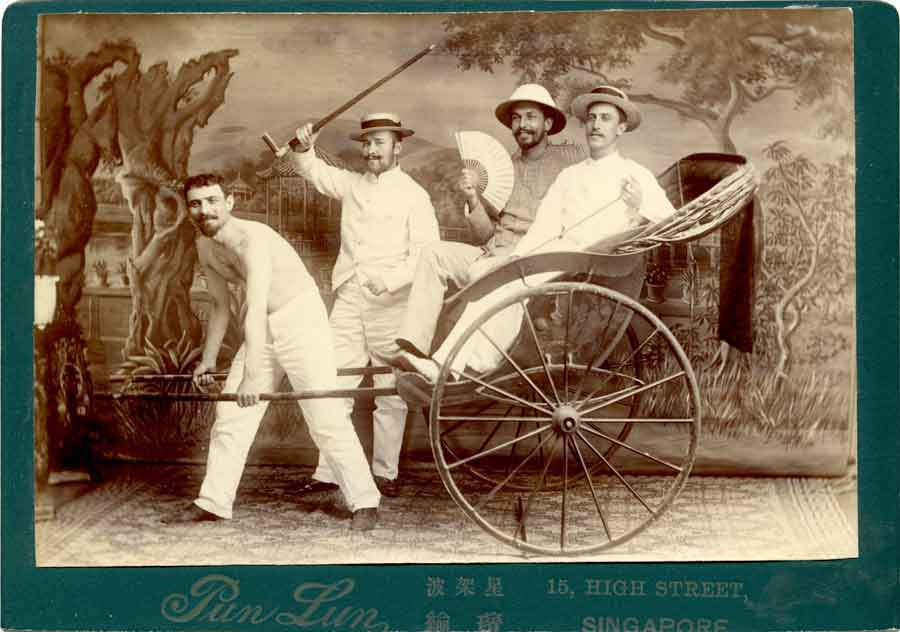

As they emerged in the late 1880s, many of the firms were run as Chinese family businesses and were patronized by all classes of customers. A spirit of fun is apparent in the many rickshaw comedies played out by Europeans in the Pun Lun studio (fig.22). What the Chinese operators thought of this is not recorded.

|

Fig 22: Pun Lun, Singapore. Rickshaw pantomime. Albumen or pop cabinet card Photoweb collection

|

All studios used their card mounts as advertising and all aspired to a European model with crests, mottos, medals, and promises of "negatives kept". The cards of Tan Tjie Lan, who ran a busy studio in Batavia, revealed his many credentials. Increasingly in the period from the 1880s to the early 1900s, locals step into the frame of the studio, often presenting themselves as mirror images to the "types" anonymously shown in the earlier decades.

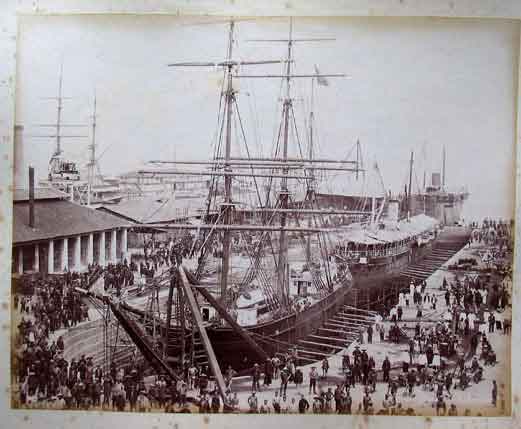

The views of the docks made in the 1890s by Tan Tjie Lan and G, R, Lambert and Company of Batavia and Singapore respectively (figs. 23, 24) are revealing of other changes, as photography became easier and could capture action. In the Lambert photographs of Tanjong Priok we see a huge crowd of Indian and Chinese dockworkers who were probably there to load coal. They have been marshalled to stop for the photographer. They look up to where the camera is, high above them, awaiting the signal that they must stop, look up - and then get on with their work.

|

Fig 23: G,R, Lambert & Co, Alexnder Koch director, American sailing ship, Tanjong Pagar dry dock, 1892.

Albumen silver photograph, 21,7 x 27,2 cm National Museum of Singapore [1993-00285-022]

|

| |

|

Fig 24: Tan Tjie Lan. KPM inter-island boat Reaet from Aceh at Tanjung Priok dock. Jakarta, around 1895.

Albumen silver photograph, 18,2 x 247 cm National Gallery of Australia. Verso of a Tan Tjie Lan cabinet card |

With new cameras and faster films, shooting people as they moved about was much more successful. When Tan Tjie Lan photographed the S,S, Reale departing Batavia for the outer islands, the photographer is amongst the action. No one has been ordered to stop; the viewer is down on the level of the port and its citizens.

What can be glimpsed through the range of standard topographical and souvenir images from Asian ports is the daily life largely hidden from official cultural images, but also the modernization of Asian port cities linked by the maritime trade routes of the Western nations across the globe. The full history of the photographers of Asia, including the few women practitioners from the late nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century, such as Thilly Weissenborn in Java, and indeed the Asian photographers who fanned out across Asia, is yet to be written.

A considerable number of Indian-operated studios catering more or less exclusively to local customers also appeared. These evolved unique forms of coloured and decorated images that reflected Indian art and religious practice as pilgrimage testaments.

Personal family photography using the Kodak cameras and processing agents, the growth of popular photographic travel guides, and the mass-market publications in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century eventually brought an end to the local studios providing the bulk of portraits and views as original prints for albums.

Then it became more about putting yourself in the picture in the family album. It became more about saying I live here, I visited there, or being personally taken by the author on a journey through images in a book (fig. 25).

|

|

|

Fig 25: Unknown French amateur Kodak

Photographer. Singapore Vue prise de L'Hotel de L'Europe and Shanghai votre serviteur en brochette i [self portrait], around 1895.

Gelatin silver photographs. Photoweb Collection

|

The role of professional views and events photography moved to the picture press rather than the original print purchased as a souvenir from a photography studio or hotel. Whatever their personal success in their new profession or hobby, the images left by the pioneer immigrant and local photographers who first set up in the ports of Asia are now the treasured visual heritage of the lands they visited as well as their homelands.

Like novels and other art forms, photographs are contrived and opinionated. They are theatrical set-pieces governed by the many technical limitations of their lack of colour, action, and atmosphere, which painters could easily include or invent to suit.

The photographic medium's compensating privilege is that as the viewer bends to peer into the image there is that frisson of a moment and a space shared over time. This is what the photographer chose to see that day, that moment; this is how the subject was cast and performed for the camera.

Regardless of original purpose or client, once a photograph was made and circulated and finally archived, it shaped how subjects and viewers were seen and how they understood themselves, and how they are seen by future generations. In the early twenty-first century, the legacy of the pioneer photographers in the port cities of Asia is being rediscovered, exhibited, and revalued, and subject to new scholarly analysis.

|

Fig 26: Albert Honiss,

Fort Santiago the Pasig River wall of the Intramuros [walled city] looking east to the opening into Manila Harbour and roadstead where ships await unloading, around 1880.

Four-panel panorama, albumen photographs over three album pages, Musee Guimet, Paris. Click on image to enlarge |

Notes

- Woodbury to Ellen Lloyd,4 May 1857; in Elliott 1996, letter no, 15,

- There are many "Asias" and no single directory exists, British Library curator John Falconer has placed his extensive "Biographical dictionary of 19th century photographers in South and South-East Asia" online: www,luminous-lint,com, See also Falconer 1987, For Sri Lanka, see New Delhi 2015, For Indonesia see Rotterdam 1989, including listings of 471 photographers, of which just under half are Chinese and a quarter Japanese, Terry Bennett's histories of photography in Japan, China, and Korea are a major source of directories, and his current work on Indochina will also provide a future directory for that region, Information of Thai photographers is available largely in Thai,, but Joachim Bautze's Unseen Siam: Early Photography, 1860-1910 is forthcoming, There is no Philippine directory as yet, but see Gael Newton's Southeast Asian national surveys and individual artist entries in Hannavy 2008 and in Ghesquiere 2016,

- Chris Furedy, "British Tradesmen of Calcutta 1830-1900: A Preliminary Study of Their Economic and Political Roles" in Sealy 1981, pp, 48-62,

- 4 In 1849-50, French baron Alexis de Lagrange (1820-1880) used French printer Louis- Desire Blanquart-Evrard's paper negative process to record Indian monuments, five of which were published in Blanquart-Evrard's Album photographique de /'artiste et de /amateur of 1851, Dr John Murray in Calcutta made superb mammoth plate calotype negatives of Indian antiquities, which he published in London in 1858; these were some of the earliest Asian photographs on view in Europe, See Sabeena Gadihoke, "Indian subcontinent, 1839-1900" in The Oxford Companion to the Photograph, edited by Robin Lenman (Oxford, 2006), Only a few Indian daguerreotypes returned to Europe and they were mostly used as the basis for engraved illustrations in pictorial papers such as The Illustrated London News.

- Chris Furedy,"British Tradesmen of Calcutta 1830-1900: A Preliminary Study of Their Economic and Political Roles", in Sealy 1981, pp,48-62, ujujuj.yorku.ca/furedy/papers/ko/ BTC1830.doc, accessed online June 2015,

- The local paper reported that a daguerreotype camera was successfully demonstrated in Sydney on 15 May 1841, See Wood 1996, The first professional, George B, Goodman from London, arrived the following Christmas; a Japanese merchant imported a daguerreotype camera into Yokohama in 1841, although he was unable to get satisfactory results; but the Daimo took an interest later in 1857 and a portrait survives,

- I am grateful to independent scholar Raimy Che-Ross of Canberra for advice that the ship may have been the East India Company steam frigate S.S. Sostiros, which was sent to Amoy in 1841, The US Navy's Africa Squadron under Matthew Perry passed through Asia from 1842, and in 1843 daguerreotypist George R, West was part of the American Treaty of Wanghia, led by Congressman Caleb Cushing on USS Brandywine, and signed in Macau on 3 July 1844, West (around 1825-59) became the first photographer to work in China in 1844, and opened the first studio in Hong Kong in 1845, The preparations listed taking a daguerreotype camera, See p, 137, http://www,forgottenbooks, com/readbook_text/Americans_ in_Eastern_Asia_1000282628/153, accessed 10 May 2015,

- Singapore-based French scholar Gilles Massot has proved that the daguerroetype of a temple in Pondicherry attributed to Itier was taken on 22 July 1844, by civilian mission member Natalis Rondot, and is the earliest securely dated photograph of India, See "Jules Itier and the Lagrene Mission" in History of Photography 39, no, 4 (November 2015), pp, 319-47,

- See "Towards a History of the Asian Photographer at Home and Abroad: Case Studies of Southeast Asian Pioneers Francis Chit, Kassian Cephas and Yu Chong", in Newton 2016,

- Gilles Massot has made a detailed study of Itier's itinerary and life, see Massot 2015,

- See Gael Newton, "Silver streams Photography arrives in Southeast Asia 1840s-1880s", in Canberra 2014, p, 16,

- See Rotterdam 1989 and Canberra 2014,

- There is no monograph on Fiebig; see John Falconer, "Frederic Fiebig" in Hannavy 2008,

- See "Photography in Madras", Illustrated Indian Journal of Arts, pt 4 (February 1832), p, 32; and "Envisioning the Indian city: Researching cross cultural exchanges in colonial and post-colonial India" [eticproject,wordpress.com],

- Gouind Narayan's Mumbai: An Urban Biography from 1863, edited by Murali Ranganathan (New Delhi, 2009), p, x,

- The most extensive discussion is Sandra Hapgood, Early Bombay photography (Mumbai 2015),

- See Canberra 2014 for Woodbury & Page, van Kinsbergen, Sachtler, and Thomson in context,

- These were run by Europeans, with the exception of Felix Laureano (1866-1952), a Filipino who ran successful studios in the Philippines, India, and Barcelona

- Falconer 1987

more of Gael Newton's Essays and Articles

|

Click on the image above for the video production on the Port Cities exhibition:

Port Cities guest curator Peter Lee shares on the life of Cornelia van Nijenroode, and how her story provides an insight to the dynamics of Asian port cities between the 16th to 20th century.

|

| |

|

Port Cities: Multicultural Emporiums of Asia 1500–1900

Author: Peter Lee, Leonard Y. Andaya, Barbara Watson Andaya, Gael Newton, Alan Chong

ISBN: 978-981-11-1380-2

Pages: 220, fully illustrated in colour

Retail price: SGD 40 (including GST)

Port Cities perfectly encapsulate a fundamental human and cultural process that has existed since time immemorial – the constant mixing of things together. Such places, and the powerful cultural dynamics that took place within and between them, reflect how people, ideas, and objects circulate, and how culture is formed, spread, and shared. Four essays and a catalogue section of stunning objects make up a profusely illustrated book to accompany special exhibition Port Cities.

|

| |

| |

|

An online piece about the Asian Civilization Museum's 2016 Port Cities exhibition - click on image above

|

| |

|

For a selection of exhibition photographs - click on the image above

|

| |

The pdf of the book is now available on Academia.au - click here.

|

|