list

of photographers • biographies • exhibition

catalogue |

| |

|

|

A web based and copy-edited version of the introduction text for: Australian Pictorial Photography, published in 1979 – originally written by Gael Newton, then the Curator of Photography at the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

Gael Newton AM was Senior Curator of Australian and International Photography at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

Note: this is basically the same as the original, the content has not been updated. |

Australian

Pictorial Photography

Pictorialism is the name by which the first 'art movement' in photography was known. It began when a group of British photographers became dissatisfied with the Photographic Society of Great Britain's support for new ideas about the artistic potential of the medium. The Society favoured the scientific and commercial applications of photography which had dominated in the 1880's.

Technical advances in photography had initiated the era of the amateur snapshooter and the Kodak 'You press the button - We do the rest' formula. However, a new class of amateur, often financially able to devote time to their hobby, wished to do the opposite. They were interested in making expressive pictures by the camera.

In 1892 a group led by George Davison and other members of the Photographic Society of Great Britain seceded to form the Linked Ring Brotherhood and began a photographic salon of their own.

The new art photography was stylistically dependent on a mixture of impressionism, naturalism and art nouveau. It spread quickly until by 1903, it was possible to form an International Society of Pictorial Photographers. The formation of the Photo-Secession in 1902 by American Alfred Stieglitz saw the leadership of the movement pass out of British hands.

By 1909 the Linked Ring had dissolved and Stieglitz had rejected the pictorial concept of art photography as confusing 'art likeness with art'. Pictorialism as an avant garde had finished by 1914. By the 1920's many alternative, more purely photographic concepts of expressive photography had been developed in the work of photographers like Paul Strand, Edward Weston and Henri Cartier Bresson. Pictorialism came to be seen as a blind alley. It was felt that to achieve respectability as an art, pictorial photography had betrayed the inherent realism of the camera.

Australian photographers were generally unaware of the directions taken by the Photo-Secession or the alternative styles of the 1920's. It appears that no copies of Camera Work, the Photo-Secession journal, reached Australia, other than one of July 1909 in Harold Cazneaux's possession. Australians relied on British magazines such as the Amateur Photographer and the annual Photograms of the Year for their knowledge of new trends. Both publications became increasingly conservative from the time of the breakaway by the PhotoSecessionists.

In Australia the formation of photographic journals for the amateur market was the foundation for pictorial photography. In 1892 the first volume of Harrington's Photographic Journal (H.P.J.), was published in which short articles on 'art-versus-photography' appeared from time to time. In 1894 when the Australasian Photo-Review (A.P.R.) was launched readers were able to follow the controversies in Britain over the new art photography.

Both magazines were published by photographic firms and gave their attention to either professionals or snapshooters. By the turn of the century the artistic amateur had begun to oust the professional as the star attraction for the less gifted hobby amateurs.

The first issue of the A.P.R. had called for the formation of a photographic society in Sydney and the Photographic Society of N.S.W. (New South Wales) was duly established in 1894. Older societies existed and others followed. It was through the monthly competitions and annual exhibitions of such societies that the new group, the pictorialists, emerged within the next few years. In particular the South Australian Photographic Society (S.A.) and one of its members John Kauffmann, are credited with introducing pictorial photography in 1898.

Such was the claim in Jack Cato's The Story of the Camera in Australia (1955) based on information from Harold Cazneaux, and Leslie H. Beer's introduction to The Art of John Kauffmann (1919). Between 1950-52 Cazneaux wrote many letters to Cato concerning the history of photography in Australia. Cazneaux often referred to how he had been inspired to take up art photography by seeing the work of John Kauffmann and David Blount, an English pictorialist, at the international salon of the S.A. Photographic Society around 1897-98.

Cazneaux would have been able to see work by Kauffmann in 1897 but the society did not hold international salons until 1902-3. Kauffmann had returned from ten years in Europe studying photography in 1897 and joined the .S.A. Photographic Society. He exhibited work independently at Baker & Rouse showrooms in Adelaide and Sydney in 1897 and at the local and interstate photographic societies' annual salons. Kauffmann's work won medals at these exhibitions and was, more significantly, given enthusiastic reviews in the newspapers.

The Australian Star of October 8, 1897 praised Kauffmann's work as 'some of the most perfect everseern and described the 'delicate tones and tints' as 'clear and truly artistic'. Other notices were on similar lines and suggest that there was no earlier photographer's work to compare with the new arrival. Certainly the extent of the press coverage of a photographer's work seems unprecedented.

By 1901 Kauffmann was invited to judge the S.A. Photographic Society's annual salon. The Register of October 1, declared it the finest ever seen with some works being'mistaken for works of art', owing to the absence of 'all the sharp and hard lines usually associated with photography'. Kauffmann was no longer the sole exponent of a new and obviously impressionistic style.

The S.A. Photographic Society was encouraged by the success of the 1901 salon to hold the first international salons in 1902 and 1903. The international content was largely the work of David Blount, a rising British pictorialist with successes at the London Salon. Blount worked in gum bichromates, one of the new printing processes favoured by pictorialists, which was capable of giving a very graphic, impressionistic effect to the image as well as a surface like a lithograph.

Whether Kauffmann was directly responsible for the appearance of pictorial photography is not certain. The Adelaide art scene was already in favour of impressionism in painting. No other pictorial work earlier than Kauffmann's has been located though a contemporary, Fred Radford of Adelaide, had a work entitled 'An Impressionist Photo' illustrated in the Photograms of the Year 1899 and wrote an article 'Impressionist Photography' in the A.P.R. of the same year. Radford's style was more exaggerated soft focus, and impressionistic than Kauffmann's who worked in a naturalistic, but atmospheric style at this time.

In 1903 the Photographic Society of N.S.W. eclipsed the S.A. society's annual with an international salon which included the work of Edouard Steichen as well as Blount. Artists such as Sid Long now reviewed the salons in the A.P.R. and H.P.J. Pictorialism was sufficiently widespread for the editorial of the December A.P.R. to note the 'old friends from the fuzzy wuzzy school'. The Victorian Amateur Photographic Association held an interstate salon with a loan collection of pictorial work from The Royal Photographic Society in London in 1905.

The A.P.R. review in the February issue attributed the dominance of the 'art aspect' to the effect of such books as H. P. Robinson's Pictorial Effect in Photography (1869). Both Cato and Cazneaux referred to the following decade as the era of low tone atmospheric style - the 'fuzzy wuzzy' era.

In 1911 the Photographic Society of N.S.W. held a large salon and even larger ones in 1912 and 1917 entitled 'Australian Pictorial Photography'. An important feature of these years was the appearance of one-man shows beginning with Harold Cazneaux's in 1909, H. Cartwright, T. C. Cummins and John Kauffmann in 1910 and Norman Deck in 1912. Cazneaux had a second show in 1912 and Kauffmann in 1914 (shown in Sydney and Melbourne).

By 1917 however, at the annual salon of the Photographic Society of N.S.W. a reaction had begun against the low tone impressionism in photography. The editorial and review by Syd Ure Smith, in the December 1917 issue of the A.P.R., complained at the limitations of copying the effects of the traditional arts and called for more 'photographic' quality.

The Sydney Camera Circle (of which Ure Smith was an associate member) had already been formed in late 1916. The aim of the 'Circle' was to get photography out of the rut of low tone and to develop a real Australian pictorial photography with 'Australian sunshine' not 'English mists'.

Two earlier groups, the Melbourne Camera Club of 1902 and the Victorian Pictorial Workers Society (1914), were similar in their dedication to raising the standard of pictorial photography but were not so nationalistic. All three had membership by invitation only and were modelled on The Linked Ring.

The Sydney Camera Circle was formed by James Stening, Harold Cazneaux, Cecil Bostock, James Paton and W. S. White, all members of the Photographic Society of N.S.W. and all concerned with the declining vitality of the work at exhibitions. The original six members were soon joined by another dozen by the end of 1917.

The 'Circle' was most active and successful around 1920-21 when they won a medal at the Amateur Photographer Colonial competition and exhibited at the London Salon and Scottish Salon. As well, an exhibition of 'Circle' members' work was shown at the Kodak Salon in 1921.

It was reviewed under the title 'The Artists of the Camera Circle' by Alek Sass in the A.P.R. in the February issue. Perhaps stimulated by the 'Circle', the Photographic Society of N.S.W. held a big exhibition in 1922 when it was decided to form an Australian Salon to match the London Salon.

|

|

|

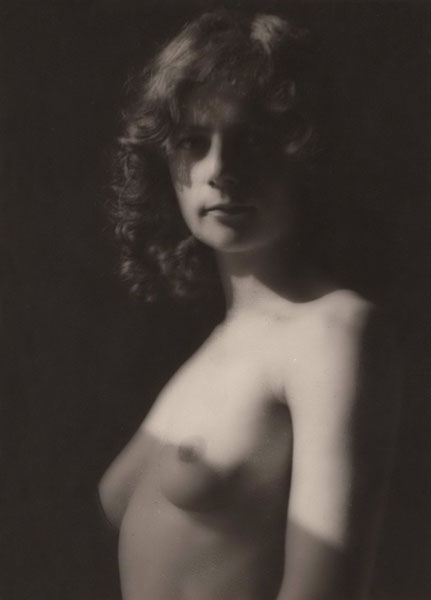

| Cecil

W Bostock, Nude Study 1915-1917, cat no 2 |

|

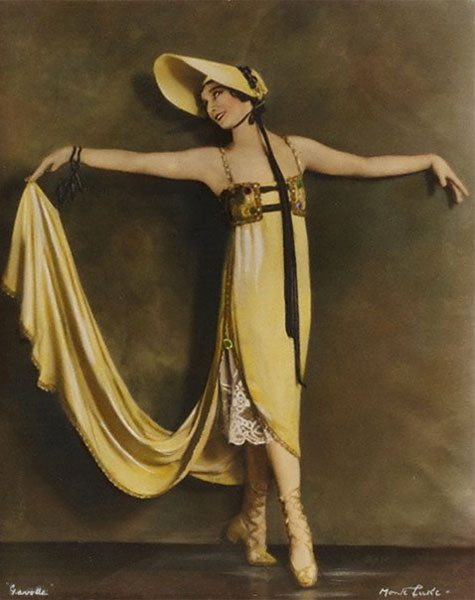

Monte Luke, Gavotte

1926/1929, cat no 67 |

The Australian Salon was formed and held exhibitions in 1924 and 1926 which were accompanied by elaborate catalogues designed and edited by Cecil Bostock and titled 'Cameragraphs'. The Salon however did not become annual and leadership passed to the Victorian Salon after it was formed in 1929. A second Melbourne Camera Club formed in 1933 by Clive Stuart Tompkins and others was largely responsible for maintaining regular salons.

In 1928 the Royal Photographic Society showed an exhibition of Australian Pictorial Photography. It was a long desired recognition of national success but came as the pictorial movement in Australia was about to be overtaken by a younger generation interested in the 'new objectivity' in European photography. Many of the original amateurs in pictorial photography had become professionals like Cazneaux, Bostock, Kauffmann and Morris.

|

| Harold Cazneaux, Razzle Dazzle 1908, cat no 18 |

| |

|

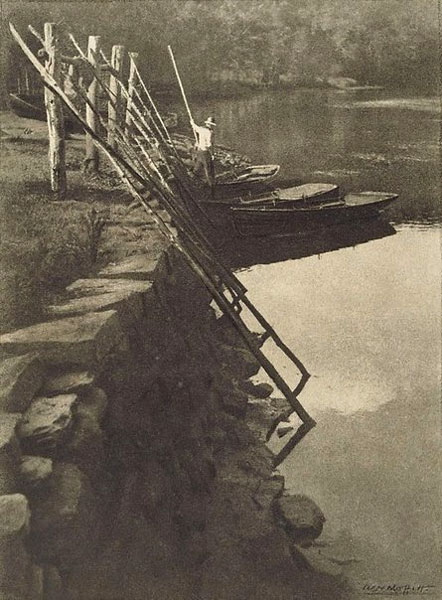

| W H. Moffitt, Boats - Berowra Creek c.1930's,

cat no 81 |

To a certain extent their clients' taste for modern clear lines and geometric shapes encouraged them to expand their pictorial vocabulary. Cazneaux produced a remarkable series of pictures beginning with images such as 'Martin Place' (cat no 23) and ending with his industrial pictures which welded the romantic atmospheric effect of pictorialism with the angles and dramatic forms of the new era. Kauffmann who was considered old fashioned by 1920 also produced surprisingly modern close-up floral studies and used industrial and everyday objects in a way very different from the usual pictorialist picturesque composition.

Modernism in art, however, had been well known from the early twenties. Jean Curlewis writing in the Sydney Number of Australia Beautiful, The Home Pictorial Annual of 1928 commented on the contemporary transition from the old to a new machine age and asked whether “in a year or two hence we shall lead our visitors to Walsh Bay or Darling Island and bid them mark the pattern of bold masses and intricate detail made against the sky by wheat silos.”

By 1932 Max Dupain had begun a series of formal studies of Pyrmont wheat silos which were totally alien to the pictorialists' eyes. Pictorialism became in that instance a period style with an arbitrary definition of what constituted art. It was no longer synonymous with art photography.

Overseas of course the pictorial concept of art photography had been superseded by the actions of Alfred Stieglitz and the Photo Secession as early as 1909. By 1930 a concept of abstract form in photography had arrived in Australia from largely German influence through Das Deutsche Lichtbild annuals. Stieglitz had shown Paul Strand's abstract images in 1917 in the last issues of Camera Work - the Photo Secession journal which had first shown the best pictorial work.

In 1938 The Contemporary Camera Groupe (sic) was formed as an alliance of artists and photographers interested in progression. Cazneaux, Bostock and Morris were members along with Max Dupain, Laurie Le Guay and Damien Parer and others. Bostock designed the catalogue but the foreword strikes a passionate note not known in pictorial circles: "We hate the cliché, and would drive a wedge between stagnant orthodoxy and original thought of the living moment."

Earlier the same year the photographic societies had organised a vast international salon to mark the 150th Anniversary of the foundation of Australia. The subtitle, the 'Finest Exhibition of Modern Photography', caused Dupain to protest in a letter to the Sydney Morning Herald that the European section did not represent photographers like Man Ray and Moholy Nagy and expressed no contemporary spirit of 'modern adventure and research', but was photography designed 'to soothe the nerves after a weary day at the office' (S.M.H. March 30).

Pictorialism, which had been started by passionate amateurs, had become the province of part time photographers unwilling to allow their hobby to disturb their life or emotions.

Gael

Newton

May, 1979

list

of photographers • biographies • exhibition

catalogue